Date: Thu, 6 Oct 2011 23:39:13 +0200

One woman's journey to trace her unknown family

By Atika Shubert and Teo Kermeliotis, CNN

updated 7:24 AM EST, Thu October 6, 2011

* Writer Hannah Pool was adopted as an infant from an orphanage in

Eritrea and grew up in England

* At 19, she found out that her father was alive and well in Eritrea

* Years later, Pool embarked on a journey to trace her unknown family

(CNN) -- For years, all Hannah Pool knew was that her biological parents had

died shortly after her birth.

An Eritrean-born girl adopted as an infant by a British academic, Pool found

herself spending her first years in Norway before landing in the UK at the

age of seven.

At times, she remembers, growing up in the northwest English city of

Manchester as a Norwegian-speaking black girl with a white father was a

source of confusion for people around her.

"When I was walking down the street holding my dad's hand, people would

sometimes check that he wasn't sort of taking me, that he wasn't kidnapping

me," says Pool, who today is a writer and journalist in the UK.

"There were lots of incidents like that which actually are just part of my

upbringing, part of my DNA almost -- I'm used to having to explain myself,

explain what I'm doing in the room, explain my relationship, whether it's

with my dad or my brother or my sister," she adds.

Almost two decades after she left the Eritrean orphanage where she was

adopted, Pool received a letter from the east African country informing her

that her father was alive and well, living back home with her brothers and

sister.

The news left the then 19-year-old Pool reeling.

"It was a complete shock," she recalls. "And it wasn't a creeping thing like

'maybe you have a cousin' or 'maybe you have an aunt' -- it was like BAM!

'you have a father,' BAM! 'here are your brothers and here's your sister,'"

she says.

"My head went into a spin, I didn't know what to do or how I was supposed to

respond to this -- was I supposed to get on a plane and go to Eritrea, was I

supposed to go back to all the people who I told my story to and tell them

'actually that story is not right, this story is right' and the whole sense

of the story of me was just pulled from beneath me like a rug."

Shocked by the revelation, Pool initially decided to ignore it and continue

her university studies in Physiology.

But the thought she had a large family living in Eritrea was always with her

"as a kind of an itch." So about 10 years later Pool felt that she had to

get on a plane and travel to her birthplace.

Meeting her father and the rest of her family for the first time

face-to-face was "incredibly emotional," says Pool. At the same time

however, it was completely different to what she had expected.

"It was almost like an outer-body experience -- I watched myself go in the

room, I was quite detached, I was surprised."

"The thing that hit me the most was the language and I hadn't prepared for

that -- I had prepared for this beautiful reunion where everybody looked the

same as me and we all kind of connect immediately.

"And it wasn't like that and the main barrier at the time was the language."

I wrote the book that I wish had been around when I was tracing myself.

Hannah Pool

Pool quickly understood that her European upbringing was marking her as

different in her birthplace, in a similar way that her Eritrean background

was singling her out in the UK.

"I thought I'm going to feel at home with everyone and initially that's how

I felt -- I stepped off the plane and thought 'wow, I'm at home, this is

where I belong,' but I realized very quickly that actually I do stand out

from everyone."

Since then, Pool has visited Eritrea three times. She describes her

relationship with her family there as a "work in progress" and has started

learning Tigrinya -- the local language -- in order to help her have a

"normal family relationship."

A talented writer, Pool documented her journey to trace her family in a book

entitled "My Father's Daughter," a project that took about a year to

complete.

"I wrote the book that I wish had been around when I was tracing myself,"

she says. "There are a lot of books about adoption but usually it's from the

point of view of the parents, there's very little from the point of view of

the adoptees ... and I think it's important to get the debate they're in

from their perspective."

An emotional memoir, Pool says the hardest part was not writing the book but

going through the whole experience -- initially, she was afraid of how her

fathers would respond to the book but in the end they were both very proud

and supportive, she says.

"Both reactions were the best reactions I could possibly hope for," she

says.

An extract of the book was also published in Tigrinya in an Eritrean

newspaper.

"That was amazing to see," says Pool. "To see that my family were able to

read an extract of my book on their own language -- that was a really proud

moment for me, that was incredibly important for me, and they were really

amazing about it."

Today, Pool proudly describes herself as British-Eritrean and says she would

love to make the African country her home one day.

"I'm proud to be Eritrean and that's something that has come with time, with

tracing and knowing where I'm from."

http://i2.cdn.turner.com/cnn/dam/assets/111003030253-african-voices-hannah-p

ool-2-00044128-story-body.jpgDiscovering an unknown family

But a few years later, Pool's already unconventional life took an even more

astonishing twist.

http://i2.cdn.turner.com/cnn/dam/assets/111003030343-african-voices-hannah-p

ool-1-00021001-story-body.jpgAn upbringing of discovery

http://i2.cdn.turner.com/cnn/dam/assets/111003032705-african-voices-hannah-p

ool-3-00042603-story-body.jpgReunited with an unknown family

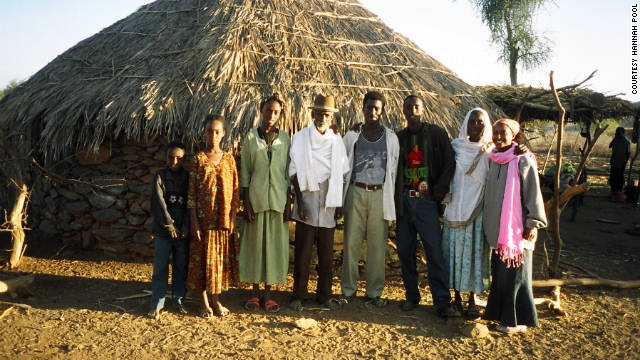

Hannah Pool with her father (in the middle wearing a hat) and other family

members in Eritrea.Hannah Pool with her father (in the middle wearing a hat)

and other family members in Eritrea.

HIDE CAPTION

Hannah Pool in Eritrea

------------[ Sent via the dehai-wn mailing list by dehai.org]--------------

(image/jpeg attachment: image001.jpg)

(image/jpeg attachment: image002.jpg)

(image/jpeg attachment: image003.jpg)

(image/jpeg attachment: image004.jpg)