<

http://www.independent.co.ug/cover-story/5642-sudan-conflict> Sudan

conflict

By Andrew M. Mwenda

Sunday, 22 April 2012 15:49

How Khartoum is using South Sudan to hide a rebellion by its own people

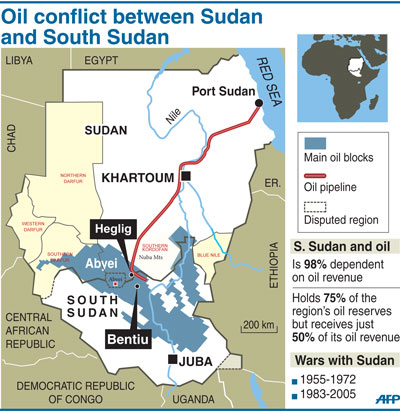

The low intensity conflict between the new state of South Sudan and the

Republic of Sudan has escalated into a near full-scale war. On Monday April

9, the Sudanese Peoples' Liberation Army (SPLA) took control of the

strategic town of Heglig from troops loyal to Khartoum. That same day,

Khartoum launched a series of air raids, bombing the towns of Bentiu and

Mayom. In the ensuing fight, SPLA shot down two of Khartoum's MIG 29 jets.

On Wednesday April 11, the United Nations Secretary General, Ban Ki-Moon,

called the President of South Sudan, Salva Kiir Mayardit, saying "I am

ordering you to pull your troops out of Heglig." On Thursday morning, Kiir

addressed the parliament in Juba where he told a cheering crowd that he had

said to Moon on phone: "I am not under your command so I cannot take orders

from you." The United States ambassador to the United Nations, Susan Rice,

called on both parties to cease hostilities. As the week ended, South Sudan

was in full military mobilisation.

The war between north and south Sudan is a complex international issue.

Khartoum accuses the SPLA of launching aggression on its territory; that is

why it has retaliated by bombing South Sudan's positions. Technically,

Khartoum is right: the troops fighting it are SPLA soldiers. Yet Juba denies

involvement in the war in Northern Sudan. Although the soldiers fighting

there belong to the SPLA, they are actually not from South Sudan.

It is this part of the jigsaw puzzle that has to be understood if

international efforts to end the conflict are to bear fruit.

Khartoum is notorious for exclusion, marginalisation and oppression of many

communities in its territory. The civil war in Sudan that led to the signing

of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2005 was between many of these

marginalised communities against Khartoum. Given its oppressive ways, one

could even say that most Sudanese are marginalised by the Khartoum regime.

However, the more distinctly marginalised groups included people in the

territory currently known as South Sudan, South Kordofan (where most of the

intense fighting has been taking place) and eastern Sudan especially areas

around Red Sea Mountains. This region is occupied by different tribes close

to the Ethiopians and Eritreans. In fact eastern Sudan is the poorest and

most marginalised region of the Republic of Sudan. And finally, there is

Darfur, the most known conflict in Sudan.

The territory currently known as the Republic of South Sudan was a separate

entity from the rest of modern day Sudan until 1947 when the British

colonial government integrated it into Sudan. Although this is the region

where the SPLA was born, it was not the only region with grievances against

Khartoum. Thus, when SPLA was formed, communities from South Kordofan and

Blue Nile region that had grievances against Khartoum joined the SPLA. Even

marginalised groups from Darfur who did not form part of the SPLA got

inspiration and training from it. Therefore, by the time the CPA was signed

in 2005, communities from these regions other than Darfur formed two

divisions of the SPLA.

When South Sudan seceded, the divisions of the SPLA from these regions

remained inside northern Sudan. When Khartoum failed to meet their demands,

they too launched a war of liberation. Khartoum has used this to claim that

it is under attack from South Sudan and has won sufficient international

support with this claim. Secondly, it has also used it as an excuse to

attack South Sudan, now an independent state, thereby triggering an

international war.

Complex contradictions

Knowledgeable sources say that many of these communities felt betrayed by

the SPLA when it signed the CPA which paved way for the independence of the

south from the rest of Sudan. They had fought alongside the SPLA for more

than two decades and felt that the independence of South Sudan would leave

them in a relatively weaker position.

However, sources say, the main faction of the SPLA that formed the new South

Sudan promised to pressure Khartoum to reach an agreement with its former

allies in these marginalised regions. It also promised them support if

Khartoum failed to accommodate their concerns. But Khartoum seems to have

had little interest in addressing the grievances of these communities. The

question is why?

Contrary to what people think, Khartoum had a strong interest in the

secession of South Sudan. This seems contradictory because most states

prefer to hold onto their territories even at extremely high costs. This is

especially so for Khartoum because most of the oil (80%) is in South Sudan;

one would expect it to fight to keep the south. Yet there were many more

complex factors that seem to have driven the National Congress Party (NCP)

of Gen. Omar Al Bashir, the President of the Republic of Sudan, to desire to

let South Sudan go.

The interest was not one way. There were people in the SPLA faction that

came from South Sudan who wanted to leave the union for independence. But

SPLA was never united on this issue and in a series of internal debates, the

movement accepted a compromise that created an opportunity for unity and if

that could not work, go for independence. Therefore, there was a convergence

of different but compatible interests between Khartoum and the South Sudan

faction of the SPLA/M for separation.

By the time the CPA was signed, the only marginalised group of the wider

Sudan that had developed both the military and political capacity to

effectively challenge Khartoum was South Sudan. To put it the other way, the

most militarily and politically strong faction of the SPLA/M was that

largely drawn from the South. Khartoum seems to have calculated that if it

got rid of South Sudan, it would effectively break up the SPLA/M in the

middle, separating the strong part of from the weaker one.

In Khartoum's calculus, this would mean that the most effective fighting and

politically organised machine of the SPLA would have little interest in

helping the other marginalised regions to fight Bashir's regime. The

remaining camp of the SPLA/M inside the older Sudan would now be weak and

easy to crash. It is this calculation that drove Bashir to sign the CPA,

seeing it as an opportunity to shed off his major threat, weaken internal

resistance and open the way for him to subdue what remained of that

resistance.

SPLA's dilemma

Meanwhile, within South Sudan, there were differences too on how to deal

with their allies from the other regions of Sudan. Some people in the SPLA/M

felt that they should not abandon them. But doing this would undermine

progress towards independence and perhaps drag the war on for many more

decades. In fact, sources say, former SPLA leader John Garang wanted to keep

a unified Sudan. He only signed the CPA, which recommended independence for

the south, because it had a clause clearly stating that both the north and

the south should work for unity.

Admirers and enemies in the south and north say Garang was very ambitious

and wanted to be president of a bigger entity than a small "fiefdom" called

South Sudan. However, there were other voices led by Kiir, Garang's deputy

and current president of South Sudan. These felt that unity was an

unrealistic ideal and separation a more realistic objective. The clause that

both sides should work for unity and separate if that ideal failed to work

was the key compromise between the Garang and the Kiir factions of the

SPLA/M that made the CPA possible.

Although Bashir's NCP wanted separation, many people in Khartoum did not

support this objective. Thus, many political forces opposed to Bashir saw in

Garang a patriot willing to keep the country united. These opposition forces

now became internal surrogates of Garang in Khartoum. Thus when he went to

the capital to be sworn in as Vice President under the CPA in May 2005,

Garang was welcomed as a hero by both the "African" and "Arab" elite and

rank and file. One million people turned up in Khartoum to give him a

heroes' welcome, a factor that was not missed by the Bashir regime and some

forces inside the SPLA/M who preferred secession.

When Garang died two months later, it was the final nail in the coffin of a

united Sudan under Khartoum. The new SPLA/M leader, Salva Kiir, was highly

committed to separation. In an ironic twist of fortunes, Kiir's greatest

ally was Bashir and his apparatchik inside the NCP. As said earlier, it was

a convergence of different but compatible interests. Kiir wanted secession

because he did not think unity was a viable option but also because he did

not want the south to share its oil wealth with people who had suppressed

them for years. Bashir wanted secession because it would help him get rid of

his strongest enemy from the union.

But this strategy was fraught with pitfalls because it did not resolve the

problem of the other marginalised groups that formed a weak but significant

portion of the SPLA. How were those SPLA divisions drawn from South

Kordofan, Nuba and Blue Nile regions going to be handled? Would it be South

Sudan to disarm them? Would they become an independent entity with whom

Khartoum would negotiate? Before all these issues could be digested, there

was an issue to deal with first.

In 2010, there were general elections in the whole of Sudan for a president.

SPLM had promised to contest the elections and actually fielded a candidate,

but an unknown entity called Yasir Arman.

Salva Kiir himself kept out of the election in order, many observers now

say, to ensure that Bashir wins. Many people say that if Garang was still

alive he would have contested the elections. If he did, it was very likely

that he was going to win as he would have attracted the votes of all the

marginalised communities and the votes of many Khartoum Arabs who preferred

a united Sudan.

Garang's potential for victory is evidence in the fact that the candidate

SPLA became a strong contender in the election for president. Realising that

he was likely to win, the SPLM on March 31 pulled him out of the race three

weeks to the election. Yet in spite of this, Arman got 22% of the vote. One

can only speculate how much Garang would have gotten had he been alive and

decided to run in that election.

This also means that had Kiir run in that election, he would have most

likely beaten Bashir hands down. However, critics of Kiir say he lacked such

high ambition and self-confidence as Garang to aspire to rule the whole of

Sudan. They accuse him of securing a deal with Bashir which allowed both of

them to capture small fiefdoms. However, supporters of Kiir say he was much

more foresighted and realistic than Garang.

Kiir's supporters argue that sections of the north that hated Bashir wanted

to keep the south not because they love unity but because of its oil. They

had been unable to unseat Bashir and saw in Garang an instrument they could

use to get rid of their rival. According to this view, the army, police and

all security agencies of the old Sudan are controlled by the northern

"Arabs" and so is the bureaucracy, judiciary, diplomatic service, education,

healthcare - everything. If any southerner had been elected president, he

would be unable to change the entire system overnight. So he would become a

hostage of these deeply entrenched interests who would be strong enough to

sabotage his plans or even kill him.

Kiir's supporters argue that in his big vision of a united Sudan and his

ambition to lead it, Garang was blind to this fundamental reality that would

have made him an ineffective president to serve the interests of the south.

The best way to serve the people of the south was independence as this would

give them an independent nation with oil revenues to sort out many of the

issues dear to their people. It is this argument that tilted the dice in

favour of Kiir and his supporters. But how would the south handle those in

its ranks who came from the other marginalised regions? SPLA promised to

urge Khartoum to negotiate with them.

Dodgy Khartoum

Although South Sudan has constantly asked Khartoum to find accommodation

with these SPLA fighters, Khartoum has consistently dodged the issue. Thus,

when these groups (camps of the SPLA) decided to renew the civil war against

the regime in Khartoum, the reasons why Bashir was dodging negotiations with

them became apparent. Rather than accept responsibility of the war or see it

as an internal rebellion against the marginalisation policies of his

government, he accused Juba of launching an aggressive war against his

government - a perfect excuse.

The situation in Sudan is exactly like the one that Uganda faced in October

1990 when elements of the Ugandan army crossed the border and attacked

Rwanda. Then-Rwandan president Juvenal Habyarimana argued that the Ugandan

army had invaded his country. Technically he was right. But in fact he was

lying. The soldiers were Rwandan refugees who had been living in Uganda and

had joined the Uganda army. They had escaped from it to launch their own war

against his regime. But Habyarimana was able to use this "evidence" to

convince the world that his country was under attack from Ugandan troops.

Using highly skilful media propaganda, Khartoum has also been able to

effectively convince the international community that it is South Sudan that

had invaded northern Sudan. It is in this context that the UN's Ban called

President Kiir to demand that South Sudan troops withdraw from Sudan

territory.

It gets more intriguing given that Khartoum has resisted all attempts to

clearly demarcate the border between the two countries, making it difficult

to establish whether the positions that the SPLA troops under the command of

Juba have entered the north's territory or not.

As things stand, the conflict between the Juba and Khartoum is only a small

sideshow, a smoke-screen to hide the more fundamental issue of the demands

of other marginalised regions inside the old Sudan. How will pressure on

South Sudan by the international community solve the internal problem of the

demands by groups in South Kordofan, Blue Nile and Nuba regions for good

treatment and inclusion? It will be interesting to see how Khartoum will

continue hiding the fact that it is not South Sudan but its own people who

have taken up arms against it.

http://www.independent.co.ug/images/stories/issue210/sudan-map.jpg

------------[ Sent via the dehai-wn mailing list by dehai.org]--------------

Received on Sun Apr 22 2012 - 10:01:17 EDT