<

http://www.independent.co.ug/column/interview/5677-somalia-museveni-and-mil

itarising-the-region> Somalia, Museveni, and militarising the region

May 04, 2012 12:19

By Andrew Mwenda and Mubatsi A. Habati

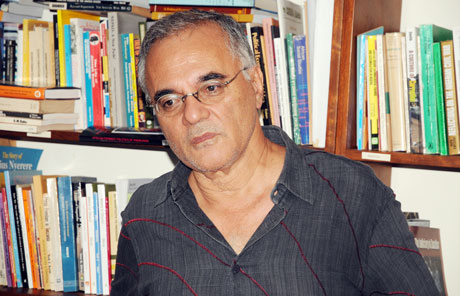

This continuation of a conversation between The Independent's Andrew Mwenda

and Mubatsi A. Habati and leading political philosopher, Prof. Mahmood

Mamdani, focuses on regional issues.

Q: Prof. Mamdani, Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia and Burundi have troops in

Somalia. It is the first time Kenya has troops in a foreign country. What do

you think are the implications of militarisation of the region?

Let us step back a little to understand the basic problem with the present

strategy which is looking for a military solution in Somalia. The problem

becomes clear if you look at Northern Uganda.

One of the biggest achievements of NRM was the use of a broad-base

government for those who would give up armed struggle. Even leaders, not

just remnants from the Idi Amin regime, but of the Obote II and Okello

administrations, were welcome in the broad-base. But the NRM closed the door

when it came to the political north. They refused a political solution when

it came to the leadership of Alice Lakwena and Joseph Kony. The north could

have its representatives in parliament but the NRM insisted that the

solution for the region must be military. Uganda's challenge today lies in

finding a political solution to the Kony problem. Even when Kony has no more

than a few hundred fighters around him, the LRA has become a justification

for the entry of US forces in the region, leading to its militarisation.

Everybody knows the solution in Somalia is political not military. Even if

there is a military victory in Somalia, it will not be sustainable without a

political solution. Every attempted military solution in Somalia has made

the problem worse because it has ignored the centrality of the political

dimension. We all know that the Union of Islamic Courts was beginning to

turn around the situation in Somalia. It was creating law and order yet it

was branded some kind of al Qaeda and demonised by the US. The military

intervention instead created the political space for al Qaeda to come in. It

pushed those in the Union of Islamic Courts unwilling to capitulate into a

corner. As they became desperate for allies, al Shabaab was born; which is

still more an umbrella of various groups than a single solid organisation.

Secondly I think there is a competitive element in this regional bid for

Somalia. There is a competitive element to militarisation, South Sudan has

shown that there is a peace dividend and commercial one after war. The

Ugandan officials have been asking what's going on since Uganda supported

the war but the oil refinery is going to Kenya. We seem to be in place in

times of war but clueless when the guns go silent.

Q: What are the implications for Uganda's involvement in Somalia?

I think the Congo war introduced some element of jealousy in the Ugandans.

They envied the military capacity of Angolans and Zimbabweans. Uganda wanted

to be the Angola of this part of the world but did not have the means, which

for Angola came from oil. Uganda solved the problem by finding an ally in

the US. Thus was born the Somalia project. I think Uganda's military

presence in the region is pegged on that. Somalia is Uganda's claim that we

have a solution for your security concerns in the region. It fits very

nicely with the American claim that the primary problem of Africa is not

development, nor democracy, nor even the lack of human rights, but security.

Q: Do you think the East African Community countries will be able to secure

political federation by 2014 as projected?

No it's not possible. I think you have to look at the 1970s to understand

why the community collapsed. It's not true that the arrival of Amin led to

the collapse of the community. Problems began very soon after independence.

Kenya had been the headquarters of the Community during the colonial period.

The common services were centralised in Kenya; the Common Market had a

Kenyan flavour. So Tanzania, joined by Uganda then, asked for a

decentralisation of industries. Thus was born the 1964 Kampala agreement

whereby each country was allocated a specific industry producing for the

region. But there was no way of punishing a country for flouting the rules.

Tanzania began the Tanzam (Tanzania-Zambia) railway financed by the Chinese.

To finance the local cost of the Railway, there was an agreement allowing

Chinese goods preferential access to the Tanzanian market, even if this

flouted common market rules. It began a tit for tat, and partners became

competitors, then rivals. Tanzania under Nyerere was beginning to move

southwards. The challenge for EAC is that Tanzania is not willing to enter

into federation because it does not think its interests will be achieved.

The Tanzanians have legitimate political concerns. Uganda and Kenya have to

come up with assurances. It may be better to think of a confederation as a

first step to a federation.

Q: What do you think of Rwanda and Burundi presence in the EAC?

I think it is a good thing for them and for us. It would be great for Rwanda

because it has been unable to come up with a solution to the political

trauma after the genocide. You cannot ban the Hutus and Tutsis from

organising themselves in a situation where Hutu and Tutsi have operated as

mobilising identities for political parties. You can only do this as part of

a power-sharing project. I think Nyerere understood this. So did Museveni if

you judge from his willingness to follow Nyerere's leadership in Burundi. If

Rwanda was accepted in a much larger community where the competition is no

longer between Hutu and Tutsi, they will both be minorities in a larger East

Africa. The larger the group, the more the necessity for alliances. In this

world you cannot exist alone.

Q: South Sudan is on tension with Khartoum. What are the implications on

Uganda and EAC if the two countries fight? Don't you think Uganda would be

dragged into the war?

It will not just be dragged into the war; Uganda is likely to see it as a

continuation of the war of liberation. The problem between the two Sudans is

more serious than the conflict between Eritrea and Ethiopia. We need to look

at the background to understand the reasons for the current fighting. Garang

had this idea of New Sudan. He understood that for South Sudan to win the

fight for independence he had to find allies. He found these in Darfur and

South Kordofan. The people in these border regions were mainly opposed to

the independence of South Sudan; they thought it a betrayal to the larger

cause of a New Sudan.

Immediately after independence SPLA was divided; one group saying Sudan is a

foreign state and it is not our business now, the other group was saying no;

we have a political commitment to support our allies in South Kordofan. The

big fight in South Kordofan is about the SPLA; they have forces fighting

alongside militias in South Kordofan against the Sudan army, and Sudan is

saying this is an invasion. It is a serious conflict. In the Mbeki

mediation, South Sudan wanted to focus on oil first but Sudan was calling

for a focus on border demarcation so they can patrol the border against SPLA

infiltration. South Sudan refused.

Q: Why?

Because they had soldiers on the other side of the border; that would mean

withdrawing from South Kordofan, Nuba Mountains, Blue Nile. These are part

of Sudan.

Q: Kenya has found oil, Uganda has oil and Tanzania has gas. What do you

think will be the implications of this on the politics and economies of

these countries?

It is going to be a big challenge especially in Uganda where the entry of

oil money coincides with the politics of succession. All the factions, even

inside the NRM, all are preparing for succession and all are aware that the

inflow of oil is likely to coincide with succession. So we will have the

toughest challenge because we will be making a transition to an oil economy

alongside a political transition. I think Kenya is in a better situation

because in spite of the levels of corruption there, Kenyans have shown an

internal capacity for political reform; just look at their ability to reform

the Constitution and tame the power of the executive. The problem in Kenya

is the ICC process which has introduced an external element. The ICC has no

political accountability inside the country; its political accountability is

to the UN Security Council.

Q: What do you think are the risks of the ICC indictment and prosecution to

Kenya?

We know the violence in the Rift Valley was tied to social issues like right

of land ownership. One side says land is a tribal right. The other side says

land is marketable and can be bought and sold by any Kenyan. Thus it is the

right of a citizen. This is the same notion that is playing out in Darfur:

who owns the land, is it tribal or national? The problem is you cannot solve

the social question in the courts. You cannot even solve the political

problem in the courts. The ICC will try individuals, and leave Kenya to

solve the political and social problems. Will the selective trial of

particular politicians, and not others, make the political problem worse?

Q: What social and economic implications will oil discovery in the region

have on the fast tracking of EAC integration?

The weaker the institutions the bigger the challenges; the fast tracking of

the EAC is more of a media gimmick. No one wants to be against the EAC in

public. So there is no public debate, which is for the worse.

Q: Rwanda and Uganda have been at each other's throat but they seem to have

fairly improved their relations. Do you think it will last?

Museveni has always had a good sense of knowing which way the wind is

blowing and he can change in response to the change in wind. Some conclude

from this that he has no principles; others say that he is pragmatic. He

changes with the demands of the circumstances. I think Museveni has

demonstrated a remarkable ability to see things from a medium term

perspective and to act in an interest larger than just individual.

Q: So what wind did he see?

He can't afford to be overthrown. Museveni claims that Uganda has a

disciplined and effective military force. This is the claim he is trying to

establish in Somalia. But this claim was successfully challenged in Congo.

The UN accused both Uganda and Rwanda armies of corruption in Congo. The

difference was that the beneficiaries in the Ugandan case were individual

officers but in Rwanda it was the state. That tells you the difference in

institutional discipline between the two.

Global

Q: Tell us your feelings about the Occupy Movement in the West and what does

it say about the structural tensions inherent in post-cold war capitalism?

The interesting move is that the West is learning from the rest. The Occupy

Movement was an effect of the Arab Spring in Egypt. They were inspired by

Tahrir Square. The history of protest in the West as elsewhere is very long.

Protests were an event: people would come to a particular place, make or

listen to speeches, sing, march, and then go home. The new thing about

Occupy Movement is go to a place and stay there. The idea was for a small

dedicated group to maintain a constant presence, like a magnet which could

attract others as supporters.

http://www.independent.co.ug/images/stories/issue211/mamdani.jpg

------------[ Sent via the dehai-wn mailing list by dehai.org]--------------

Received on Fri May 04 2012 - 06:37:19 EDT