From: Biniam Haile \(SWE\) (eritrea.lave@comhem.se)

Date: Tue Apr 28 2009 - 15:04:24 EDT

Horn of Africa demands full U.S. attention

4/28/2009 8:40:01 AM

By Michael Smerconish

It would be easy to dismiss the threat posed to U.S. security in the

Horn of Africa as the stuff of wayward, rogue teenage pirates.

Especially given the way Navy SEALs were able to dispense with those

holding Capt. Richard Phillips this month.

But as I first learned two years ago after getting to play military

tourist at the invitation of the Defense Department, our military thinks

otherwise.

I was part of a military immersion called the Joint Civilian Orientation

Conference that the Pentagon has been running since 1947 for handpicked

civilians. My trip was to Centcom, military-speak for the command

covering some of the hottest spots in the world: Iraq, Afghanistan,

Pakistan, and 24 other nations. The Centcom area is home to 651 million

people and 65 percent of the world's known oil supply.

So it was surprising to learn that Ethiopia and Djibouti would be the

final stops on the weeklong trip. While a last-minute security warning

prevented our visit to Ethiopia, we did tour a military humanitarian

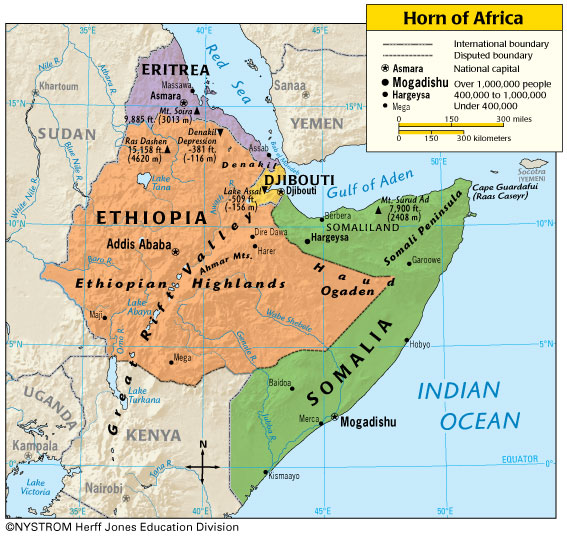

outpost in Djibouti. Located in the northeast corner of the continent,

Djibouti borders the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea, next to Somalia. It's

about the size of Massachusetts and is 94 percent Muslim.

Camp Lemonier, a former French Foreign Legion post, is home to the U.S.

military there. That's where Rear Adm. Richard Hunt, the commander of

the Combined Joint Task Force of the Horn of Africa, and W. Stuart

Symington, U.S. ambassador to Djibouti, led a briefing in a makeshift

movie theater.

They showed a short but impressive video about the problems of the Horn

of Africa and the unique ways in which our military is addressing them.

Beginning in 2002, Hunt and Symington said, the military had sought to

"win the peace" by advancing a largely humanitarian effort to ensure

that Djibouti and neighboring nations weren't overrun by terrorists

seeking to establish a new haven.

"We do this so we don't get an Afghanistan," explained Hunt. He referred

to the area as "phase zero" in the war on terror, and he said that we

need to "change the environment to prevent conflict." The ambassador

agreed. "The conditions to support terrorism are ripe," Symington said.

So it wasn't surprising to see that Africa was given its own command

(Africom) soon after my trip ended. No longer are Djibouti and seven

other African nations being lumped as part of Centcom. And now we know

why.

The sea-bound knaves hijacking cargo ships are terrorists. Sure, they're

looking for money, not martyrdom. But make no mistake, terror is their

tool of choice. And referring to them as "pirates" distracts from the

real danger to which we've finally become fully attuned.

The region boasts many of the circumstances the United States

encountered in late 2001 after invading Afghanistan. Large swaths of

lawless territory. Thousands of armed militia members. An underlying

drug culture (opium in Afghanistan and khat, a psychotropic shrub they

chew to get high, in Somalia) that heightens tensions among the roving,

armed thugs.

In today's Somalia, al-Shabab ("The Youths"), a terrorist organization

in the vein of the Taliban, is the landlocked answer for the "pirates"

of the Indian Ocean. That group asserted responsibility for firing

mortar rounds at a plane carrying U.S. Rep. Donald Payne, D., N.J., out

of Mogadishu on April 13.

David Shinn, former State Department coordinator in Somalia and the U.S.

ambassador to Ethiopia from 1996 to 1999, told me that while it's

important to avoid overstating the links between al-Qaida and al-Shabab,

those links do exist.

Indeed, Osama bin Laden praised al-Shabab and others in an audio message

released last month: "Your patience and resolve supports your brothers

in Palestine, Iraq, Afghanistan, the Islamic Maghreb, Pakistan, and the

rest of the fields of jihad."

Fazul Abdullah Muhammad, a former al-Qaida operative in Nairobi who is

wanted for the 1998 bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, is

now among the al-Shabab corps. So, too, are Abu Taha al-Sudani, formerly

an al-Qaida leader and financier in East Africa, and Salah Ali Salah

Nabhan, wanted for questioning related to a 2002 hotel bombing in

Mombasa, Kenya.

It's dangerous to label this simply a "piracy" problem. Or to subscribe

to the notion that sending multiple warships to aid one captain held

captive by four young "pirates" was over the top. Terrorism -- whether

motivated by religious fanaticism, perverse national pride, or money --

is already a large part of the thread of the region. And those are

conditions ripe for organizations like al-Shabab and al-Qaida to

exploit.

It has been two years since Hunt expressed to me his concern that the

Horn of Africa could become another Afghanistan. In the years since

Sept. 11, 2001, the United States has let the real Afghanistan fester

back into a hub of terrorism and extremism.

Here's hoping we don't make the same mistake twice.

Michael Smerconish writes a weekly column for The Philadelphia Inquirer.

http://www.postbulletin.com/newsmanager/templates/localnews_story.asp?z=

12

<http://www.postbulletin.com/newsmanager/templates/localnews_story.asp?z

=12&a=396667> &a=396667

<http://www.nystromnet.com/information/maps/images/HornOfAfrica.jpg>