webmaster

© Copyright DEHAI-Eritrea OnLine, 1993-2010

All rights reserved

From: Tsegai Emmanuel (emmanuelt40@gmail.com)

Date: Thu Nov 25 2010 - 12:18:14 EST

Saudi Arabia's Succession Labyrinth

November 25, 2010 | 1701 GMT

Summary

Saudi King Abdullah is in the United States after having successfully

undergone treatment for complications from a blood clot. With the prospect

of succession looming — Crown Prince Sultan has been ill with cancer for

many years, and both leaders are in their 80s — a shift in the kingdom’s

leadership is likely to take place at a time of tectonic change, both

domestically and in the region. While the Saudi monarchy as an institution

has been remarkably resilient since the unification of the kingdom in 1927,

the challenge posed by the retirement or death of the current top Saudi

hierarchy made up mainly of the founder’s sons and the ascension of the next

generation — which is far larger and less close-knit — will be daunting.

Analysis

Saudi King Abdullah bin Abdul-Aziz has undergone a successful surgery in the

United States to address a blood clot complicating a slipped spinal disc,

according to a statement from the royal court on Nov. 24. The deteriorating

health of the aging monarch comes as 82-year-old Crown Prince Sultan bin

Abdul-Aziz, the king’s half brother, is suffering from cancer and has been

spending much of his time resting in his palace in Morocco. The crown

prince, who is also the country’s deputy prime minister, minister of defense

and aviation, and inspector general, returned to Saudi Arabia on Nov. 20 to

see to the affairs of the state in the king’s absence. The actual health

status of both men remains opaque but, given their ages and medical

histories, it is safe to assume that the kingdom will soon see a transition

of power.

Since 2005, when Abdullah ascended to the throne after the death of his

predecessor, King

Fahd<http://www.stratfor.com/saudi_arabia_what_will_happen_after_king_fahd>,

the Saudi kingdom has been engaged in a slow transition of power from one

generation to the next. Besides King Abdullah, there are some 19 surviving

sons of the founder of the modern kingdom, of whom only four can be

considered likely successors to the throne given their current positions and

influence. This means the grandsons of the

founder<http://www.stratfor.com/saudi_arabia_younger_faces_enter_fray>,

a much larger group, will very soon dominate the hierarchy of the Saudi

state. So long as power was in the hands of the second generation,

succession was not such a difficult issue and was dealt with informally.

However, due to the massive changes occurring both within Saudi Arabia and

in the wider Middle East, this transition will come at a particularly

difficult time for the next-generation leadership that, despite the formal

processes for succession instituted by Abdullah, will likely be far less

unified than the current one.

That said, the al-Saud regime has proved to be remarkably resilient over the

course of its history, remaining in power despite the forced abdication of

the founder’s successor, King Saud, in 1964; the assassination of King

Faisal in 1975; and the stroke-induced incapacitation of King Fadh for

nearly a decade until his death in 2005, when King Abdullah took the throne.

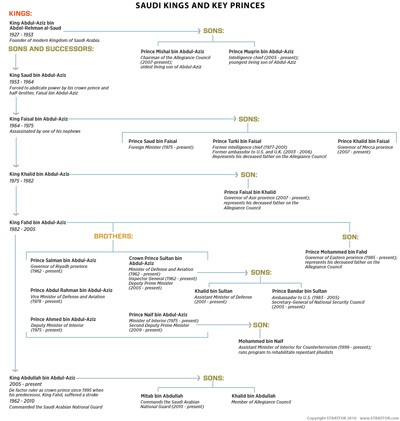

<http://web.stratfor.com/images/middleeast/art/Saudi-family_LG.jpg>

The stability of the second generation’s leadership can be attributed, at

least in part, to three key clans of the royal family acting as checks on

one another. These include the Faisal clan, named for the successor to King

Saud, who succeeded Saudi Arabia’s modern founder, King Abdul-Aziz bin

Abdel-Rehman al-Saud; the Abdullah faction, named for the current king; and

the Sudairi clan, named for the founder’s eighth wife, Princess Hassa bint

Ahmad al-Sudairi. While Byzantine in its complexity, this balance has

prevented incessant power grabs by King Abdul-Aziz’s hundreds of

descendants.

The Three Main Clans

The clan of former King Faisal includes Prince Saud, the current foreign

minister, and Faisal’s other two sons, Prince Khalid, governor of Mecca, and

Prince Turki, who served as the kingdom’s intelligence chief from 1977 to

2001. The Faisal clan has somewhat weakened in recent years. Prince Turki,

after briefly serving as ambassador to the United States and the United

Kingdom from 2003 to 2006, currently holds no official position, though he

remains influential. His older full brother, Prince Saud, who has been

foreign minister since 1975, is 70 years old and ailing, and could step down

soon.

Despite his influence over the years as head of the Saudi Arabian National

Guard (SANG) from 1962 to 2010, crown prince from 1982 to 2005, and de

factor ruler since 1995, King Abdullah’s faction is numerically small; he

has no full brothers who hold key posts, and thus his clan is made up of his

sons. King Abdullah’s most prominent son, Mitab bin Abdullah, recently took

over the SANG<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/20101117_saudi_kings_son_head_elite_military_force>,

and the king’s oldest son, Khalid bin Abdullah, is a member of the newly

formed Allegiance Council, set up to govern the succession process. Mishal

bin Abdullah assumed the post of governor of the southern province of

Najran, while another son, Abdul-Aziz bin Abdullah, has been an adviser in

his father’s royal court since 1989.

The Sudairis have held a disproportionate amount of power, due in part to

the fact that their leader, the late King Fahd, was the longest-reigning

monarch of the kingdom, ruling from 1982 to 2005. The Sudairi faction

includes many powerful princes, such as the clan’s current patriarch, Crown

Prince Sultan, who serves as minister of defense and aviation and as

inspector general; the vice minister of defense and aviation, Prince Abdul

Rahman; Interior Minister Prince Naif; the governor of Riyadh province,

Prince Salman; and Deputy Minister of Interior Prince Ahmed.

Even though the crown prince’s clan is bigger and more prominent than the

king’s, the two clans remain the principal stakeholders in the Saudi ruling

family<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/20090903_saudi_arabia_satisfying_sudeiris>because

they control the two parallel military forces of the kingdom. This

has been the case since the early 1960s when then-Crown Prince Faisal — as

part of his efforts to take power from his half brother, King Saud —

appointed Crown Prince Sultan as minister of defense and aviation and King

Abdullah as head of the SANG. Since then, the two men have controlled the

two separate forces.

King Abdullah’s move to appoint his son, Mitab, to head the SANG shows that

control over the force will remain with his clan. Likewise, Crown Prince

Sultan would like to see control over the regular armed forces go to his

eldest son, Khalid bin Sultan (currently assistant minister of defense),

after Prince Sultan either decides to step down as minister of defense and

aviation or dies. But this remains to be seen since the king reportedly

opposes Khalid’s taking over the Defense Ministry.

Further complicating the situation is that, thus far, clans have been

composed of the various sons of the founder from different mothers. Now,

many of these second-generation princes have multiple wives, who have

produced many sons all seeking their share of power, adding to the

factionalism.

Setting Up a Succession Plan

Sensing that the power-sharing method within the family had become untenable

due to the sheer number of descendants seeking power and influence within

the regime, King Abdullah in 2007 moved to enact the Allegiance Institution

Law, which created a leadership council and a formal mechanism to guide

future transitions of power.

This new, 35-member body, called the Allegiance Council, is made up of the

16 surviving sons of the founder and 19 of his grandsons — a disparity that

will grow as the sons begin to die. Its purpose is to choose the new king

and crown prince when they die or are permanently incapacitated, but the new

institution remains an untested body. Perhaps most problematic, the

processes the council is set to govern are being implemented at a time when

the second generation is on its way out. Had this formal process of

succession been initiated earlier, it would have been institutionalized

during the era of the sons of the founder. They were far fewer in number and

worked directly with their father to build the kingdom, giving them a

stronger claim to authority than anyone in the subsequent generation. An

earlier start would have allowed the second generation to deal with the many

problems that inevitably crop up with any new system.

The composition of the Allegiance Council is such that it gives

representation to all the sons of the founder. This is done through either

their direct membership on the council or via the grandsons whose fathers

are deceased, incapacitated, or otherwise unwilling to assume the throne.

The reigning king and his crown prince are not members but each has a son on

the council. The council is chaired by the eldest son of the founder, with

his second-oldest brother as his deputy. Should there be no one left from

the second generation, the leadership of the council falls to the eldest

grandson. Any time there is a vacancy, the king is responsible for

appointing a replacement, though it is not known if King Abdullah has filled

the vacancy created by the death of Prince Fawaz bin Abdul-Aziz, who died in

July 2008, some six months after the establishment of the council.

When King Abdullah dies, the council will pledge allegiance to Crown Prince

Sultan, who automatically ascends to the throne. But the issue of the next

crown prince is mired in a potential contradiction. According to the new

law, after consultation with the Allegiance Council, the king can submit up

to three candidates to the council for approval. The council can reject all

of them and name a fourth candidate. But if the king rejects the council’s

nominee then the council will vote between its own candidate and the one

preferred by the king, and the candidate who gets the most votes becomes the

crown prince. There is also the option that the king may ask the council to

nominate a candidate. In any case, a new crown prince must be appointed

within a month of the new king’s accession.

This new procedure, however, conflicts with the established practice in

which the second deputy prime minister takes over as crown prince, a policy

that has been followed since King Faisal appointed Fahd to the post. In

fact, the current king, after not naming a second deputy prime minister for

four years, appointed Interior Minister Prince Naif to the post in March

2009<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/20090327_saudi_arabia_contentious_succession_decision>.

The appointment of Naif, who is viewed within Saudi Arabia as the next crown

prince and eventually the king, as second deputy prime minister after the

establishment of the Allegiance Council has already raised the question of

whether established tradition will be replaced by the new formal procedure.

The law also addresses the potential scenario in which both the king and

crown prince fall ill such that they cannot fulfill their duties, which

could transpire in the current situation given the health issues of both

King Abdullah and Crown Prince Sultan. In such a situation, the Allegiance

Council would set up a five-member Transitory Ruling Council that would take

over the affairs of the state until at least one of the leaders regained his

health. If, however, it is determined by a special medical board that both

leaders are permanently incapacitated, the Allegiance Council must appoint a

new king within seven days.

In the event that both the king and crown prince die simultaneously, the

Allegiance Council would appoint a new king. The Transitory Ruling Council

would govern until the new king was appointed. While it has been made clear

that the Transitory Ruling Council will not be allowed to amend a number of

state laws, its precise powers and composition have not been defined.

What Lies Ahead

The kingdom has little precedent in terms of constitutionalism. It was only

in 1992 that the first constitution was developed, and even then the country

has been largely governed via consensus obtained through informal means

involving tribal and familial ties. Therefore, when this new formal

mechanism for succession is put into practice, the House of Saud is bound to

run into problems not only in implementation, but also competing

interpretations.

To make matters worse, the Saudis are in the midst of this succession

dilemma — and will be for many years to come given the advanced ages of many

senior princes — at a time of massive change within the

kingdom<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/saudi_arabia_king_abdullahs_risky_reform_move>and

a shifting regional landscape.

On the external front there are a number of challenges, the most significant

of which is the regional rise of

Iran<http://www.stratfor.com/geopolitical_diary/geopolitical_diary_iranian_escalation_saudi_connection>,

catalyzed by the Shia-dominated government in Baghdad and the withdrawal of

U.S. forces from Iraq. The Saudis also do not wish to see a U.S.-Iranian

conflict in the Persian Gulf, which would have destabilizing effects on the

kingdom. To Saudi Arabia’s immediate south, Yemen is grappling with three

different insurrections<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/yemen_moving_toward_unraveling>challenging

the regime of aging Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh. In

the Levant, the Saudis have to deal with both Iran and

Syria<http://www.stratfor.com/weekly/20101013_syria_hezbollah_iran_alliance_flux>,

which each enjoy far more influence in Lebanon than Riyadh. Egypt is also in

the middle of a major transition as ailing 82-year-old President Hosni

Mubarak, who has been at the helm for nearly 30 years, will soon hand over

power to a successor<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/20100315_egypt_imagining_life_after_mubarak>—

a development that has implications

for the Israeli-Palestinian

conflict<http://www.stratfor.com/weekly/20090107_hamas_and_arab_states>,

another key area of interest for the Saudis. Even in Afghanistan and

Pakistan<http://www.stratfor.com/weekly/20090513_limits_exporting_saudis_counterjihadist_successes>,

the Saudis are caught between two unappealing options: side with the

Taliban, as they did during the Taliban’s rule in the 1990s, and risk

empowering al Qaeda-led jihadists, or oppose the Taliban and thus help Iran

expand its influence in the area.

Turkey’s bid for leadership in the Middle

East<http://www.stratfor.com/weekly/20090202_erdogans_outburst_and_future_turkish_state>is

a new variable the kingdom has not had to deal with since the close of

World War I and the demise of the Ottoman Empire. In the near term, the

Saudis take comfort in the idea that Turkey can serve as a counter to Iran,

but the long-term challenge posed by Turkey’s rise is a worrying

development, especially since the Saudi leaders’ predecessors lost control

of the Arabian Peninsula twice to the Ottomans — once in 1818 and then again

in 1891.

While the Saudis have time to deal with a number of these external

challenges, they do not enjoy that same luxury in their domestic affairs.

The Saudis have been largely successful in containing the threat from al

Qaeda, but they have had to engage in radical reforms, spearheaded by King

Abdullah, in order to do so. These include scaling back the powers of the

religious establishment<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/saudi_arabia_social_liberalization_prerequisite_economic_reforms>,

expanding the public space for

women<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/20090214_saudi_arabia_king_abdullahs_bold_move>,

changing the educational

sector<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/20090924_saudi_arabia_gradual_reform_and_higher_education>and

undertaking other

social reforms<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/20090629_saudi_arabia_royal_rift>.

These moves have led to a growing moderate-conservative divide at both the

level of state and society and have galvanized those calling for further

socio-political

reforms<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/saudi_arabia_perils_change>as

well as the significant

Shia minority<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/20090225_saudi_arabia_shiite_uprising>that

seeks to exploit the opening provided by the reform process.

Each of these domestic changes and their implications are deemed extremely

uncomfortable by the religious establishment. While thus far the Saudis have

been able to control the prominent Muslim scholars, known as the ulema

class, especially with the limits on who can issue fatwas, the potential for

backlash from the ulema remains. At the very least, the ulema will support

more conservative factions in any power struggle.

All of these issues further complicate the Saudis’ venture into uncharted

territory insofar as leadership changes are concerned. There are several

princes who have already distinguished themselves as likely key players in a

future Saudi regime. These include intelligence chief Prince Muqrin, the

youngest living son of the founder and a member of the Allegiance Council;

Prince Khalid bin Faisal, the governor of Mecca province; Prince Mitab bin

Abdullah, the new commander of SANG; and Assistant Interior Minister Prince

Mohammed bin Naif, the kingdom’s counterterrorism chief and head of the

de-radicalization program designed to reintegrate repentant jihadists.

Since May 2008, when news first broke that Crown Prince Sultan was

terminally ill<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/saudi_arabia_signs_new_political_era>,

the expectation has been that the kingdom would have a new crown prince

before it got a new

king<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/20081120_saudi_arabia_implications_crown_princes_health>.

King Abdullah’s recent hospital visit may or may not alter those

expectations. But in the end, the real issue is whether the historically

resilient Saudi

monarchy<http://www.stratfor.com/geopolitical_diary/geopolitical_diary_saudi_arabias_resilience>will

be able to continue to demonstrate resilience moving forward.