Date: Sun, 6 Apr 2014 00:53:37 +0200

One century after World War I and the Balfour Declaration: Palestine and

Palestine studies

<http://www.opendemocracy.net/author/walid-khalidi> Walid Khalidi 3 April

2014

To hug one's identity in an age of globalisation is a global phenomenon

witnessed in the break-up of states and devolution movements worldwide. The

one-staters run counter to this trend. The veteran Palestinian historian

explains how students of this history can best counter a woeful tale of

hubris.

We meet today to celebrate the second anniversary of the establishment of

the SOAS Centre for Palestine Studies. I am honoured to have been asked to

deliver this first Annual Lecture. It is deeply gratifying to be addressing

you on this occasion in the name of a sister institution—Institute for

Palestine Studies (IPS)—which has just celebrated its fiftieth anniversary

as an independent, private, non-partisan, non-profit, public service

research institute.

We at IPS look forward to long years of innovative cooperation between our

two institutions. Like other centres of Palestine studies, we are both

researching the same phenomenon: the ever-growing accumulation of debris

generated on that fateful day of 2 November 1917 by the so-called Balfour

Declaration, the

<http://www.opendemocracy.net/arab-awakening/walid-khalidi/one-century-after

-world-war-i-and-balfour-declaration-palestine-and-pal>

singlesinglehttp://cdncache1-a.akamaihd.net/items/it/img/arrow-10x10.png

most destructive political document on the Middle East in the twentieth

century.

How far this university has travelled—and how alien the idea of a Centre for

Palestine Studies would have been to Lord Balfour—can be gauged from the

oft-quoted words, dripping with Olympian disdain, he uttered in 1919:

The Great Powers are committed to Zionism. And Zionism, be it right or

wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long traditions, in present needs, in

future hopes, of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of

the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land.

The expression ‘Palestine Problem’ is shorthand for the genesis, evolution,

and fall-out of the Zionist colonisation of Palestine, which began in the

early 1880s and is ongoing at this very hour.

One century ago this year, the floodgates of World War I opened to usher the

chain of events that led to the Balfour Declaration. By the time it was

issued in 1917, almost 40 years had passed since the beginning of Zionist

colonisation, and 20 since the first Zionist Congress at Basel. Despite the

fervour of the early colonists, the movement of the Jewish masses fleeing

Tsarist rule was not southwards towards the Levant, but westwards across

Europe towards the magnetic shores of North America. A trickle arrived in

Palestine; a flood rolled across the Atlantic.

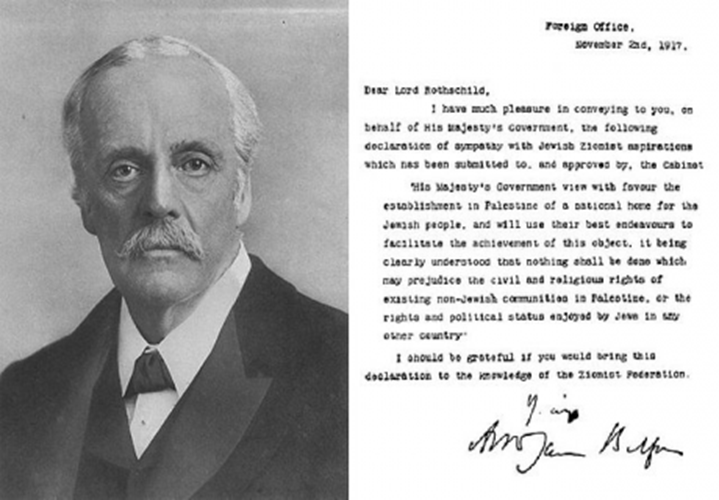

Portrait of Lord Balfour, along with his famous declaration. Wikimedia

Commons. Public domain.Most Rabbinical authorities throughout the diaspora

were hostile to Zionism for preempting the Jewish Messiah, while the

American and European Jewish bourgeoisie were embarrassed by Zionism and

fearful of gentile charges of dual loyalty.

All this changed when Britannia gave its blessing to the Zionist venture in

the Balfour Declaration. Not only did it give its blessing, it also agreed

to transform this unilateral declaration into a self-imposed obligation

guaranteed under international law in the newly established League of

Nations mandate system.

Uniquely in its governance as an imperial power, it agreed to carry out this

obligation in partnership with a foreign private body, (the World Zionist

Organisation), now elevated, in the guise of an international Jewish Agency,

to an independent actor recognised by the League for the specific purpose of

creating the Jewish National Home in Palestine.

An immediate question leaps to mind. How could London, teeming with

pro-consular expertise ripened during centuries of dealings with

multitudinous races and faiths across the globe, have fallen for the Zionist

plan?

The short answer has two-syllables: hubris. At the end of World War I, with

the US withdrawn behind a wall of isolationism and with the Ottoman,

Romanov, Habsburg, and Hohenzollern empires in ruins, British power was

paramount. King Clovis’s realm across the channel alone could challenge it.

But this was no big deal, because Sir Mark Sykes had found a handy formula

to win French acquiescence: divide the loot!

There is of course a longer answer, which is where our research centres come

in. Setting aside the trees and thick foliage of the mandate period’s White

Papers, Blue Books, and Commissions of Inquiry, our scholars would do well

to look more deeply into how and why imperial London between the two world

wars nurtured a rival imperium in imperio under its governance. The puzzle

deepens when one considers that this imperium was not only local. It had an

external dimension, an imperium ex imperio in the Jewish Agency whose major

central financial institutions and other sources of power were largely

American, putting it beyond London’s control.

Thus, when in 1939 Ben Gurion, the preeminent leader of the Yishuv, decided

to change horses, discarding the British mount (favoured by his political

rival Chaim Weizmann) for an American steed, he did so in deliberate

calculation of America’s potential as a counterweight and successor to

Britain.

The story is as old as history: the revolt of a client against a

metropolitan patron. But the erosion of Anglo-Zionist concord by the late

1930s also illustrates an iron law of politics. No two political entities

remain eternally in sync. There may be a moral here for the current

relationship between Obama’s Washington and Bibi’s Tel Aviv.

1948 onwards

The events of 1948 have stirred up more controversy than any other phase of

the Palestine Problem, giving rise eventually to a new post-Zionist school

of historiography in Israel. Its authors have been designated the New

Historians, as opposed to the Old Historians who articulated a mythical

Zionist foundational narrative.

The old narrative featured a Yishuv David facing an Arab Goliath, with

perfidious Albion bent on strangling the infant state. It also involved

hundreds of thousands of Palestinians leaving their homes, farms, and

businesses in response to orders from their leaders to make way for the

invading Arab armies on 15 May 1948.

Given the role of IPS and this speaker in the articulation of the

Palestinian counter-narrative to that of the Old Historians, it could be

useful, for the record, to share some elements of how it developed.

One of the first authoritative accounts of an early version of the Israeli

orders’ myth is given by the Palestinian historian Arif al-Arif. Arif had

been based in Ramallah as assistant district commissioner during the last

years of the Mandate, and the Jordanians kept him on as de facto civilian

governor.

In mid-July 1948, Israeli forces had attacked the Palestinian towns Lydda

and Ramla while the Arab armies a stone’s throw away stood by. The entire

population of the two towns, some 60,000 people, were forced on a long trek

towards Ramallah. They arrived there in a pitiable condition, after hundreds

had dropped along the way.

Count Bernadotte, the UN mediator, arrived in Ramallah the third week of

July. Arif, who was delegated to accompany him, was astonished when

Bernadotte told him that the senior Israeli officials he had just met had

“assured” him that the inhabitants of Lydda and Ramla had left because of

orders given to them by the town leaders.

Arif immediately arranged for Bernadotte to meet these leaders, still living

in caves and under bridges after their expulsion: Muslim and Christian

ecclesiasts, municipal councillors, judges, professionals of all kinds.

There is little doubt that this experience contributed to Bernadotte’s

recommendation to the UN on the return of the refugees, which the General

Assembly adopted after his assassination by Yitzhak Shamir’s Stern Gang.

In the 1950s, the orders myth was all over the British media. By this time

the predominant Israeli version was that the orders had been broadcast by

the top Palestinian leadership, not local leaders. The most aggressive

exponent of this version was the British journalist Jon Kimche, then editor

of the weekly Jewish Observer, the organ of the British Zionist Federation.

The top Palestinian leader, Haj Amin al-Husseini, was then living in exile

in Lebanon. I had known him from childhood and he always treated me in a

kindly fashion. When I described to him the impact of the orders’ myth in

the west, he immediately allowed me unrestricted access to his archives

(since destroyed by Phalangist forces during the Lebanese civil war in the

1970s).

I had earlier gone through reams of the BBC monitoring records of the 1948

Arab radio broadcasts kept at the British Museum in London. I added the data

from Haj Amin’s archives to the findings from the BBC records to produce my

article “Why Did the Palestinians Leave?” which was published in 1959 by the

AUB alumni journal Middle East Forum.

Soon after the article’s publication, I received in Beirut a visit from this

young Irish journalist, Erskine B. Childers, who showed great interest in

the BBC records and said he intended to examine them himself upon his return

to London. In early 1960, Ian Gilmour, owner of the Spectator, the

prestigious British weekly had just been to Israel and had heard all about

the orders from senior Israeli officials. Having read the article in Middle

East Forum, he asked many questions and left. On 12 May 1961 the Spectator

published Childers’ article entitled “The Other Exodus,” whose conclusion

was: no orders.

There ensued a crackling correspondence of readers’ letters that lasted

almost three months and in which, thanks to Gilmour, the counter-Israeli

narrative was given unprecedented exposure. An early responder was Jon

Kimche, who loftily opined: “New myths ... have taken place of old ones. The

Israelis ... have contributed their share, but more lately it has been the

Arab propagandists (Walid Khalidi and Childers).”

At the time I was on sabbatical from the AUB at Princeton, checking the CIA

monitoring records of the 1948 Arab broadcasts at the Firestone Library.

>From there, I wrote to the Spectator disclaiming acquaintance with Childers

(which was untrue), but expressing great delight that he had independently

arrived at the same conclusion as myself (which was true). I also noted that

my latest findings in the CIA records corroborated my earlier findings in

the BBC records.

As it happened, while at Princeton I had also been looking at the Hebrew

sources with the help of a sympathetic elderly Sephardic lady scholar. The

result of my research was “Plan Dalet: The Zionist Master Plan for the

Conquest of Palestine,” soon to be published, again in the Middle East

Forum. As the Spectator correspondence increasingly involved the Palestinian

exodus more generally—I weigh in with a summary of my findings. My letter

stated, inter alia:

A Zionist master-plan called Plan Dalet for the forceful occupation of Arab

areas both within and outside the Jewish State “given” by the UN to the

Zionists was put into operation. This plan aimed at the de-Arabisation of

all areas under Zionist control.

Plan Dalet aimed at both breaking the back of Palestine Arab resistance and

facing the UN, the US, and the Arab countries with a political and military

fait accompli in the shortest time possible – hence the massive and ruthless

blows against the centres of Arab population. As Plan Dalet unfolded and

tens of thousands of Arab civilians streamed in terror into neighbouring

Arab countries, Arab public opinion forced their shilly-shallying

governments to send their regular armies into Palestine.

It is the considered opinion of this writer that it was only the entry of

the Arab armies that frustrated the more ambitious objective of Plan Dalet,

which was no less than the military control of the whole of Palestine west

of the Jordan.

To the best of my knowledge, this is the first public mention of Plan Dalet

in the west.

1967 onwards

Just as World War I gave birth to the Balfour Declaration, the 1967 War gave

birth to another momentous document: UN SC Resolution 242. And just as the

Balfour Declaration is, in a sense, the fountainhead of all developments in

the Palestine Problem/Arab Israeli conflict in the twentieth century up to

and including the 1967 War, so is SC Res. 242, in a sense, the ultimate

fountainhead of all developments in the conflict throughout the balance of

the twentieth century and to this day.

Oddly, many observers look with favour on Res. 242, largely because its

preamble talks about the “inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by

war.” But in its operative paragraphs, Res. 242 does the precise opposite.

True, it talks about “withdrawal of Israeli armed forces from territories

occupied” (in the French version, “des territories occupés”), but it does

not specify the time when the withdrawal should begin, the line to which

Israel should withdraw, or how long the withdrawal should take. Nor does it

mention by name the territories to be withdrawn from.

The resolution calls for peace and “secure and recognised borders” between

all the protagonists, but it does not indicate who decides the security or

location of these borders. There is no mention of the Armistice lines. The

resolution affirms the need for a “just settlement of the refugee problem,”

but does not indicate who decides the justice of the settlement or who these

refugees are. The word “Palestinian” is totally absent, and there is no

reference to the applicability of the Geneva Conventions to the occupied

territories.

This remarkable text should be seen against the background of decisions

taken by the Israeli cabinet on 18-19 June, soon after the hostilities

ended.

Briefly, the Israeli cabinet consensus was on

(1) withdrawal only on condition of peace agreements;

(2) peace treaties with Egypt and Syria on the “basis “ of the international

frontiers and Israel’s security needs; (3) annexation of the Gaza Strip, and

(4) the Jordan River as Israel’s “security border,” implying permanent

control over the West Bank.

You don’t have to be a cryptographer to see the concordance of Res. 242 with

these specifications—or rather instructions—of the Israeli cabinet. The

focus on peace treaties with Egypt and Syria to the exclusion of Jordan is,

of course, designed to de-couple these countries from the Palestine problem

and to isolate both the Palestinians and Jordan.

On 28 June 1967, ten days after this cabinet meeting, Israel revealed its

true intentions by annexing the 2.5 sq. miles of Jordanian municipal East

Jerusalem together with an additional 22.5 square miles of adjacent West

Bank territory in an obscene territorial configuration sticking northwards

at Ramallah.

Res. 242 was an Israeli diplomatic and political victory no less momentous

than its victory on the battlefield. But it was only possible because of

President Lyndon B. Johnson. What really motivated LBJ remains a field of

study for all centres of Palestine studies. As a senator in 1956, Johnson

had adamantly opposed Eisenhower’s decision to force Israel to restore the

status quo ante and give back its “acquisition of territory by war.”

In the aftermath of the 1967 war, Israel’s foreign minister Abba Eban worked

closely with LBJ’s inner circle, including US ambassador to the UN Arthur

Goldberg. (As a member of a pre-Saddam Iraqi delegation to the UN General

Assembly right after the war, I had to listen to Eban weave his spider web

of falsehoods, but I also got the chance to rebut him).

Eban reveals in his memoirs that he urged his American counterparts to

“eradicate” from their minds the very concept of “armistice,” and to link

Israeli

<http://www.opendemocracy.net/arab-awakening/walid-khalidi/one-century-after

-world-war-i-and-balfour-declaration-palestine-and-pal>

withdrawalwithdrawalhttp://cdncache1-a.akamaihd.net/items/it/img/arrow-10x10

.png from the current ceasefire lines “to peace negotiations in which

boundaries would be fixed by agreement.” This meant that the starting point

for the negotiations would be the farthest foxholes reached by Israeli

armour deep in Arab territory. It also meant that Israel could—as indeed it

did—use the full weight of its conquests and its military superiority to

dictate the time, tempo, scope, sequence, and extent of its withdrawal.

The “regime” established by Res. 242 has been acquiesced in, if not abetted,

by successive American administrations since Johnson’s presidency. The

resolution’s opaqueness and permissiveness made possible the settlement

policy ongoing to this very hour. It is this regime that sent Sadat to

Jerusalem and Arafat to Oslo.

The 1967 War dealt the coup de grace to secular pan-Arabism, already in its

death throes. But it catapulted the Palestinian guerrilla movement to the

front ranks because it symbolised resistance for the entire Arab world after

the humiliating rout of the Arab armies. The war’s most profound and

potentially catastrophic impact, however, lies in the inspiration it gave to

neo-Zionist religious fundamentalist Messianism, and to its creation of

conditions conducive to a clash over Jerusalem’s holy places between Jewish

and Christian evangelical jihadists on the one hand and Muslim jihadists on

the other.

Palestine today

When one looks at the Palestinian scene today, one sees a people hanging by

their fingernails to the rump of their ancestral land. In such dire straits,

the topmost Palestinian priority should surely be to close ranks. This is

why the Fatah Hamas rift is so scandalous. You need your two fists to

survive. Both sides are equally to blame and both sides should be

tirelessly, relentlessly urged to reconcile. Of course the very act of

reconciliation between them would be pounced on by Netanyahu as an act of

war. But surely Israel knows that intra-Palestinian reconciliation is a must

for any Palestinian-Israeli peace.

The gap between Fatah and Hamas on the mode of struggle is wide. Abbas is

committed to non-violence. This commitment is not philosophical: as a

practitioner of violence in his guerilla days, Abbas was quietly absorbing

its cost and consequences. It is no coincidence that he was the first within

the Fatah leadership to propose a dialogue with sympathetic Israeli

interlocutors.

Abbas’ commitment to non-violence is strategy, not tactics. I know this for

certain, having listened to him and to his three predecessors: Arafat,

Shuqairi, and Haj Amin. In many ways, Abbas is a tragic figure. He is a

guerilla leader wittingly turned “collaborationist”. Every night his

security forces keep to their barracks, while Israeli commando squads prowl

the by-lanes of Kasbahs, refugee camps, and West Bank villages hunting young

militants. This is a terrible price to pay for moral high ground.

How long can Abbas maintain this policy without real progress towards peace?

How long can the Palestinians put up with his leadership?

Nevertheless it should not be forgotten that the BDS movement could not have

progressed so far without Abbas. Wide though it is, the gap between Abbas

and Hamas on the issue of armed struggle is not unbridgeable. There is

evidence of pragmatism within the Hamas leadership. And if it thinks

theologically, it can also conceive of a theological exit strategy from its

declared commitment to the armed struggle. Besides, Abbas’ commitment to

non-violence does not preclude civil disobedience. This could be the meeting

ground once the will to reconcile takes over, and the time for civil

disobedience comes.

If the Fatah/Hamas rift is dangerously detrimental to the Palestinian cause,

so is disagreement about its political goal. It is no secret that the

one-state/two states issue is a major topic of debate, not only within the

Palestinian camp, but also within a much wider circle of allies and

supporters.

As you may have surmised, I am not a congenital advocate of the partition of

Palestine—i.e., the two states formula. In fact I came to it pretty late. It

was only in 1978 that I espoused it in an article in Foreign Affairs

entitled “Thinking the Unthinkable.”

I am still a two-stater, and this is why: there is global support for a two

state solution—with the possible exception of the Federated States of

Micronesia. It would be irresponsible to forgo this invaluable asset. We

have already tried the one-state framework during the 30 years of the

British Mandate, and we know what happened even though the balance of power

was at first massively in favour of the Palestinians.

The balance of power today is crushingly in favour of the other side. Israel

is the superpower of the Arab Mashreq, thanks to the rottenness of the Arab

states system and its incumbent political elites. In a one-state framework,

Israel would have the ideal alibi to remove whatever constraints remain on

settlement. Within a twinkling the Palestinians would be lucky if they had

enough land to plant onions in their back gardens and to bury their dead

alongside.

Israel’s 1948 Declaration of Independence pledged to ensure, “complete

equality of social and political rights to all inhabitants, irrespective of

religion, race, or sex”. Now Netanyahu is insisting on prior recognition of

the Jewish character of Israel as an absolute condition of a peace

agreement.

Of the 37 signatories to the 1948 Israeli Declaration of Independence, only

one was born in Palestine. The others came mostly from Poland and the

Russian Empire: from Plonsk, Poltava, & Pinsk, from Lodz and Kaunas. These

men were mostly left of centre, but they had not come all the way to

Palestine to share their new home with its inhabitants.

When Netanyahu speaks of a Jewish state he is speaking in the name of a vast

and growing religious fundamentalist right wing nationalist constituency,

which splits Israeli Jewish society, right down the middle. The division in

the Jewish population of Israel today is no longer between left and right,

but between the secularists and the religious. Many of the secularists are

liberal and post-Zionist, but they are not in the ascendant.

In the ascendant is a neo-Zionist Messianic triumphalist religious right

settler movement allied to US Christian apocalyptic evangelism, fired by the

1967 conquest of the whole of Eretz Israel and the return of the “Temple

Mount” to Jewish military possession. This coalition considers Palestinians

Canaanites whose doom is Biblically predestined. It does not look much more

favourably on the secular Jewish Israelis. There is no consensus in Israel

on who is a Jew. Indeed we should ask Bibi for a definition of “Jewish.”

Many proponents of BDS are one-staters looking to the success of sanctions

against South Africa, but between the start of the sanctions against South

Africa in the early 1960s and Mandela’s election in 1994 there were 30

years. Time is not an asset for Palestinians in a one-state framework

despite the demographic factor.

I am not against BDS. I want it to succeed. To succeed it needs the Jewish

post-Zionists and the liberal Zionists. Delegitimise the occupation and your

chances are bright. Delegitimising Israel itself will cost you the bulk of

your Jewish allies and most of the friendly world’s capitals.

Let us have two BDS campaigns

BDS one, to end the Occupation, and BDS two, to implement the pledge to its

Arab citizens in Israel’s Declaration of Independence—in that sequence.

To hug one’s identity in an age of globalisation is a global phenomenon

witnessed in the break-up of states and devolution movements worldwide. The

one-staters run counter to this trend.

A Palestinian state is a Palestinian imperative. Palestinians need to

maintain their own link to what is left of their own ancestral soil. They

need an umbilical cord to the collective memories of their parents and

grandparents.

They need a tribune who will stand up for those of them who will remain in

their diaspora. They need to pass an inheritance to their grand children and

great grand children. They need a spot under God’s sun where they are not

aliens, stateless ghosts, or second class citizens.

Israel and the US

Just how sorry the state of the “Arab Nation” is can be gauged from the fact

that the future of Palestine hinges more on “the desires and prejudices” of

Benjamin Ben Zion Nathan Netanyahu than on those of any incumbent in the

proud Arab capitals of Umayyad Damascus, Abbasid Baghdad, Ayyubid Cairo, or

Wahhabi Riyadh.

Still, the current tripartite discourse between Netanyahu, Kerry and Abbas

is in reality a façade for the arm-wrestling marathon that has been going on

between Bibi and Obama for five years. I listed Bibi’s parentage advisedly.

His ideological template was forged by and embodied in the teachings of his

grandfather Rabbi Nathan and his father Professor Ben Zion.

Rabbi Nathan, a contemporary of Herzl’s, was a National Religious Zionist (a

rare species at the time). He was an ardent follower of Vladimir Jabotinsky,

the founder of the Zionist Revisionist movement, so named because from the

early 1920s it sought to “revise” the gradualist, dissembling strategy of

Chaim Weizmann and Ben Gurion.

Jabotinsky insisted on an unabashed assertion of the end point of the Jewish

National Home—a Jewish state through which the river Jordan flowed, not one

in which the river was the border. This goal was to be achieved, in the

shortest possible time by massive immigration, by means of an “Iron

Wall”—i.e. overwhelming military force. Ben Gurion routinely referred to

Jabotinsky as “Vladimir Hitler.”

Ben Gurion’s ardour for Jabotinsky was no less intense than Nathan’s. He

joined the Revisionist party at 18 and later edited a Revisionist daily,

entitled Jordan, which relentlessly criticised Weizmann and Ben Gurion. Ben

Zion followed Jabotinsky to the US where he became his secretary. He stayed

there for ten years spreading the Revisionist ideology, but returned to

Israel to blast Begin for his peace treaty with Egypt.

Recently, not long before his death, Ben Zion told an Israeli daily that by

“withholding food from Arab cities, preventing education, terminating

electrical power and more, the Arabs won’t be able to exist and will run

away from here.”

Bibi’s Israeli biographers report that Ben Zion tutored his sons in history

and Judaism and that they held their father in “holy reverence.” As a boy

Bibi often wanted to discuss “the two banks of Jordan principle.” If Bibi’s

grandfather and father were his formative ideological influences, his role

model in life was his older brother Jonathan, the hero of Entebbe where he

was killed in action. This is where Bibi’s swagger comes from.

Jonathan’s death traumatised father and son. To honour him they established

the Jonathan Institute in Jerusalem for the study of “international

terrorism.” Appropriately, one of its conferences was addressed by Prime

Minister Menachem Begin, though he apparently refrained from sharing his

reminiscences about Deir Yasin, or about how his organisation, the Irgun,

had introduced the letter bomb, the parcel bomb, the barrel bomb, the market

bomb, and the car bomb to the Middle East.

For Bibi, the US is as much home ground as Israel. He knew the country from

age seven: elementary school, high school, MIT, a Boston Consulting firm.

During this period he honed a Philadelphia accent and mastered baseball

vocabulary. At least three of his uncles had emigrated to the US where they

became steel and tin tycoons.

After Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, Yitzhak Shamir, then foreign

minister, sent Bibi as an attaché to the Washington embassy to help repair

Israel’s image.

Bibi was an instant success: ubiquitously glib in the media, lionised by the

major Jewish organisations. As ambassador to the UN from 1984 to1988, he

consolidated his stardom with the pro-Israeli public in the US. In 1991

Shamir, now Prime minister, made Bibi deputy minister, further feeding his

Himalayan political appetite. By 1993 Bibi was the Likud leader, by 1996,

prime minister.

A major source of insights into the relationship between Washington and Tel

Aviv is the memoirs and autobiographies of successive presidents and

secretaries of state. The space devoted to the Arab/Israeli conflict in

these writings has grown enormously in the last few decades. Curiously, to

date there has been no serious attempt to collate this information with the

other sources— another field of study for Palestine centres.

Since his Washington embassy days, Bibi has dealt in various capacities with

five US administrations. He considers the American political arena as

legitimately open to him. He believes that his writings on terrorism

convinced President Reagan to change American policy on how to deal with it.

He brags that he successfully lobbied Congress to end Secretary Baker’s

attempts to open a dialogue with the PLO, explaining that “All I did was

force him (Baker) into a change of policy by applying a little diplomatic

pressure. That’s the name of the game....”

On his first visit to the US as PM in 1996, Bibi addressed Congress,

receiving tumultuous jack-in-the-box, bipartisan ovations. A tycoon uncle

whom he had invited to the session told a US newspaper that he believed his

nephew could beat Bob Dole and Bill Clinton in a presidential race.

President Clinton complained that when Bibi came to the White House for a

visit, “evangelist Jerry Falwell was outside, “rallying crowds.... praising

the Israeli government’s resistance to phased

<http://www.opendemocracy.net/arab-awakening/walid-khalidi/one-century-after

-world-war-i-and-balfour-declaration-palestine-and-pal>

withdrawalwithdrawalhttp://cdncache1-a.akamaihd.net/items/it/img/arrow-10x10

.png from the Occupied Territories.” Clinton also complained that: “Likud

agents in the US joined Republicans to stir up suspicion against his Middle

East diplomacy.” Clinton believed that Bibi “recoiled at heart from the

peace process.” His favourite tactic was to “stall” and “filibuster” and

when challenged he would cry “national insult.”

Enter Barak Obama. Bibi, born in 1949, is 12 years older. By the time Obama

ran for the US senate in 2003, Bibi had already been UN ambassador, leader

of the Likud, prime minister, foreign minister, and was then, the incumbent

finance minister. It was probably only after Obama’s 2004 speech at the

National Democratic Convention that Obama began to loom on Bibi’s political

radar screen. Where on earth did this guy come from, and with that middle

name?? It is tempting to speculate that Bibi feels Obama is impinging on

Bibi’s own turf.

There is no time to go into the various rounds of the Obama-Bibi arm

wrestling match—the settlement freeze, Iranian nuclear ambitions, the 1967

lines, UN recognition, Hamas-Fatah agreement. Some observers believe Bibi

has “humbled” Obama. I think they are at deuce.

In the last 100 years

Since 1914, Zionism rode piggy-back first on Pax Britannica, then on Pax

Americana to establish a Pax Israeliana at the expense of the Palestinian

people. How long can it persist in its refusal to seriously address what it

has done to the Palestinians?

My hunch is that Bibi will acquiesce to Kerry’s framework proposals, but

only with the intention to stall. He thinks he can get away with it. He sees

himself as more than the prime minister of Israel. In 2010 and 2012, the

Jerusalem Post ranked him first on a list of the World’s Most Influential

Jews.

To Bibi, the Atlantic flows through Eretz Israel. Bibi knows he will outlive

Obama politically. In Israel, once a PM always a PM. Obama has less than 3

years to go. Meanwhile Bibi knows he can outflank Obama in the Congress. He

certainly has more bipartisan support there than the incumbent of the Oval

office.

All the other protagonists are committed to a peaceful resolution. Kerry is

his master’s voice, and Obama’s understanding of the Palestine problem far

surpasses that of all his predecessors. Abbas’ commitment to peace is

genuine. At his age, peace would be the crowning achievement of a lifetime.

The Gulf dynasts are panting for a resolution. They want to focus on the

real enemy: Pan-Islamic, anti-monarchical Tehran.

Bibi will never share Jerusalem. Continued occupation and settlement, while

tightening the noose around East Jerusalem, is a sure recipe for an

apocalyptic catastrophe sooner or later over the Muslim Holy Places in the

Old City. With the continued surge in religious fundamentalist zealotry on

both sides, the road to Armageddon will lead from Jerusalem.

That is why, Benjamin Ben Zion ben Nathan Nathanyahu is the most dangerous

political leader in the world today.

Professor Walid Khalidi is the Chairman of the Institute for Palestine

Studies, USA, based in Washington DC. This is the text of the speech that he

gave on 6 March 2014 as First Annual Lecture of the SOAS Centre for

Palestine Studies. The video of the lecture as well as a presentation of the

CPS are available <http://www.soas.ac.uk/lmei-cps/podcasts-and-papers/>

here.

<http://www.opendemocracy.net/files/imagecache/wysiwyg_imageupload_lightbox_

preset/wysiwyg_imageupload/537772/640Balfour.png> Portrait of Lord Balfour,

along with his famous declaration

<http://www.opendemocracy.net/files/imagecache/wysiwyg_imageupload_lightbox_

preset/wysiwyg_imageupload/537772/un50-051.gif>

http://www.opendemocracy.net/files/imagecache/article_medium/wysiwyg_imageup

load/537772/un50-051.gifThe UN adopts SC Res. 242. Wikimedia Commons. Public

domain

(image/png attachment: image001.png)

(image/png attachment: image002.png)

(image/jpeg attachment: image003.jpg)