Date: Thu, 23 Oct 2014 23:34:03 +0200

Ethiopian famine: how landmark BBC report influenced modern coverage

Thirty years on, Michael Buerk’s broadcast remains a watershed moment in

crisis reporting, but what is its lasting legacy?

Posted by

Suzanne Franks

Wednesday 22 October 2014 15.02 BST

The 30th anniversary of a key moment in modern TV journalism will be marked

on 23 October: Michael Buerk’s broadcast of a “biblical famine”, filmed in a

remote part of northern Ethiopia. The images shot by Kenyan cameraman

Mohammed Amin, together with Buerk’s powerful words, produced one of the

most famous television reports of the late 20th century.

Long before satellite, social media and YouTube, the BBC news item from

Ethiopia went viral – transmitted by 425 television stations worldwide. It

was even broadcast on a major US news channel, without revoicing Buerk’s

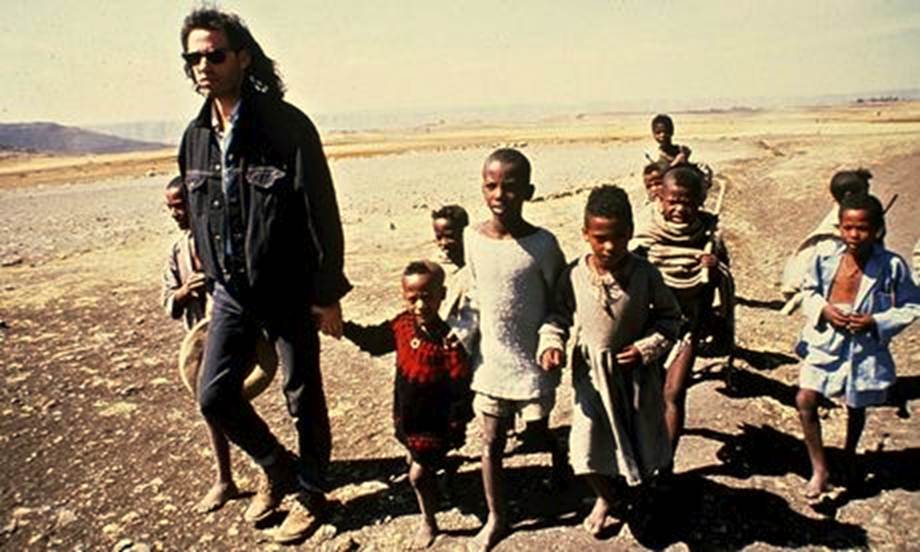

original English commentary – something that was almost unheard of. Bob

Geldof viewed the news that day and, as a result, that famine report

eventually became the focus of a new style of celebrity fundraising. This

produced another key television memory, the Live Aid extravaganza in July

1985, which itself became a transforming moment in modern media history.

In the aftermath of Buerk’s news story there were handwringing postmortems

within aid agencies and governments. Why had no one been able to focus

crucial media attention much earlier, when the widespread food shortages

were first becoming evident? The conclusion was that often a famine is only

judged to be newsworthy once horrible images are present. But, worryingly,

after

<http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2011/sep/30/e

ast-africa-crisis-soul-searching> the famine in east Africa in 2011, similar

criticism of media interest coming too late was still being made.

Today, the same thing is happening elsewhere in Africa. BBC correspondent

<https://twitter.com/Doylebytes/status/484589170468618240> Mark Doyle

tweeted in July 2014 that “famines are sexy, predicting them is not,”

drawing attention to a report on

<http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-28143584> the approaching disaster

in South Sudan. Just as in 1980s Ethiopia and 2011 Somalia, the conclusions

of <http://www.theguardian.com/books/2001/mar/31/society.politics> Amartya

Sen are being played out: famine is not a natural disaster but a result of

<http://www.spectator.co.uk/features/7141183/drought-didnt-cause-somalias-fa

mine/> social and political factors, where vulnerable groups lose their

entitlement to food.

The preference for keeping the story simple omits the crucial social and

political context of famine. In 1984 the authoritarian Ethiopian regime of

Mengistu Haile Mariam was fighting a civil war against Tigrayan and Eritrean

insurgents. It is no accident that these were the areas starving because, to

a large extent, the government was deliberately causing the famine. It was

bombing markets and trade convoys to disrupt food supply chains. Defence

spending accounted for half of Ethiopia’s GDP and the Soviet-backed army was

the largest in sub-Saharan Africa.

Yet this story of man-made misery was sidestepped. Instead, the reporting

was about failing rains, which kept things simple for both journalists and

aid agencies. This also suited an authoritarian government that did not want

foreign journalists nosing around. The UK government also stuck to the

simple narrative. The urgent departmental response group, which met daily to

brief senior ministers in reaction to the BBC news reports, called itself

the Ethiopian drought group – in the belief that this was what the problem

was all about.

It was not only the simplification that impaired the reporting but crucial

omissions and a misunderstanding of much of the aid effort. The Tigrayan

guerilla leader, Meles Zenawi, later Ethiopia’s prime minister, admitted

<http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/8535189.stm> how easily the rebels

could fool the western agencies and use the aid for military purposes.

The Ethiopian government also had deliberate strategies to manipulate

donations in pursuit of its brutal resettlement policies. Victims of famine

were lured into feeding camps only to be forced on to planes and

<https://www.culturalsurvival.org/ourpublications/csq/article/the-politics-f

amine-ethiopia> transported far away from their homes.

<http://www.theguardian.com/world/2005/jun/24/g8.debtrelief> Some estimate

the number of deaths from this policy to be higher than those from famine.

And again, the secrecy and brutality of Mengistu’s regime made it relatively

straightforward to divert aid and deceive outsiders. Some aid agencies,

including Médecins sans Frontières, realised what was happening and

protested – leading to their expulsion from Ethiopia. Others preferred to

keep quiet and stay. The minutes of the Band Aid Charitable Trust reveal

inklings of misuse and misappropriation of aid, but indicate a view was

taken that it was better not to object.

Little of this messy complexity was conveyed by the media at the time to

audiences who had empathised with the victims, donated generously and wanted

to see suffering relieved. Aid agencies know that straightforward natural

disasters are much easier to communicate than trickier man-made crises.

Fundraising for the humanitarian disaster in Syria has been difficult – a

complex story without clear goodies and baddies is not an easy one to

convey, either for journalists or NGOs.

So how much has changed since Buerk reported from Ethiopia? In 1984 the only

voices were from a white reporter and a European aid worker. A contemporary

news report would be more inclusive. But much is the same. Not only has the

problem of the media ignoring famine until it is a catastrophe and then

simplifying the explanation recurred many times, but

<http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jul/06/britain-supporting-dictatorshi

p-in-ethiopia> also some of the same abuses associated with resettlement are

still taking place in Ethiopia.

There is also the vexed question of stereotypical depictions of Africa.

After 1984 there was much examination and criticism of “African-pessimism”

and negative framing of the continent. But many images used in fundraising

and reporting Africa still rely on those same tropes. Even today, the nexus

of politics, media and aid are influenced by the coverage of a famine 30

years ago.

• Suzanne Franks, a former BBC journalist, is a professor of journalism at

City University, London, and author of

<http://www.hurstpublishers.com/book/reporting-disasters/> Reporting

Disasters: Famine, Aid, Politics and the Media

Bob Geldof with Ethiopian children Bob Geldof was at the forefront of a new

celebrity fundraising effort, sparked by the BBC’s report on Ethiopia’s

famine. Photograph: Today/Rex Features

(image/jpeg attachment: image001.jpg)