Date: Fri, 31 Oct 2014 23:23:44 +0100

Burkina Faso: Ghost of 'Africa's Che Guevara'

In the weeks before violent protests, some Burkinabes' thoughts turned to

slain leader Thomas Sankara for inspiration.

<http://www.aljazeera.com/profile/kingsley-kobo.html> Kingsley Kobo Last

updated: 31 Oct 2014 10:52

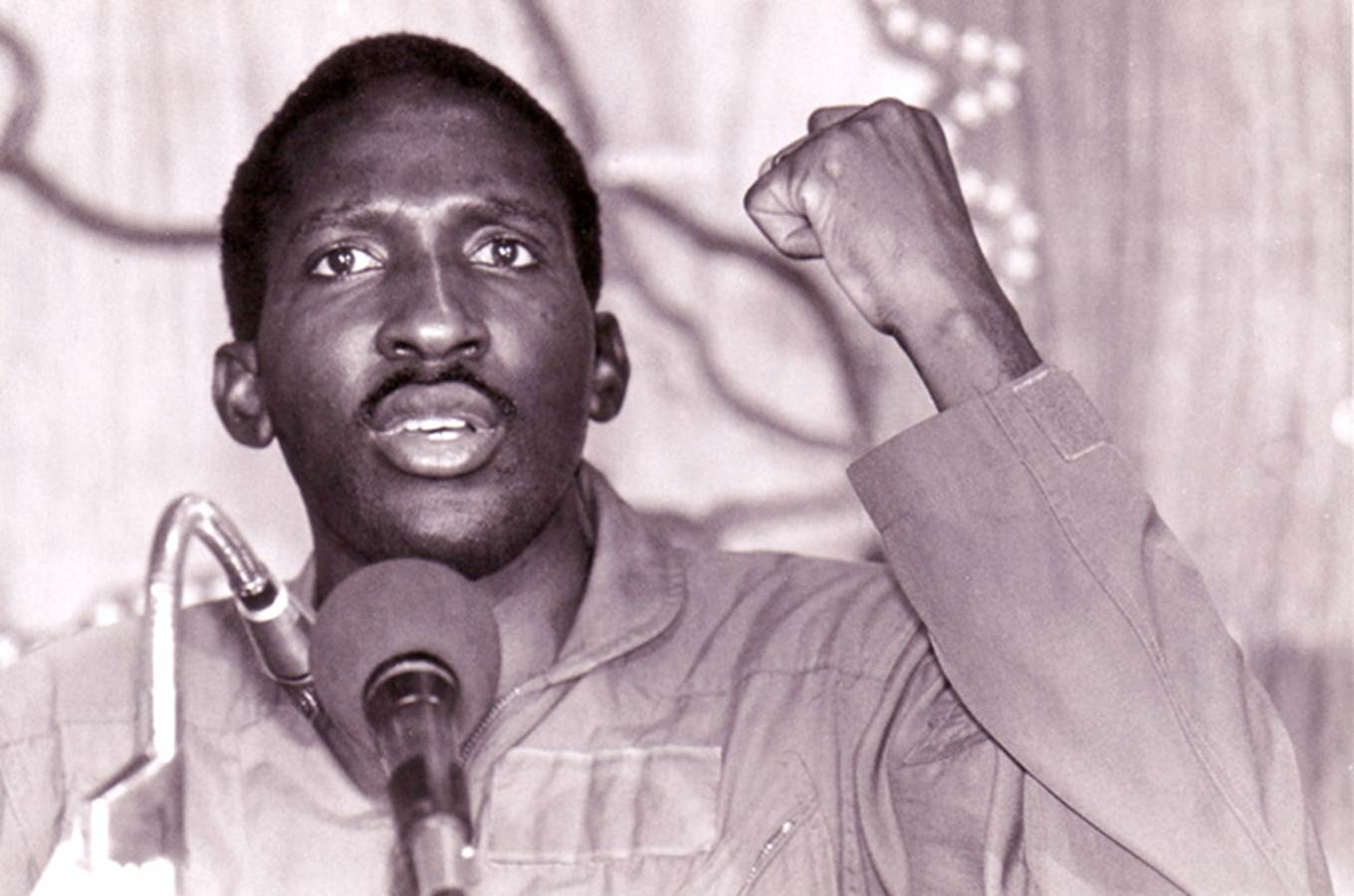

Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso - In the early hours of a night in 1987, one of

Africa’s youngest leaders, Thomas Sankara, was murdered and quietly and

quickly buried in a shallow grave.

Now, the man widely believed to be behind it, Burkina Faso's president, has

watched as his parliament was set ablaze by furious protesters who want him

gone.

Many of the protesters say the history of the slain 1980s leader partly

inspired them to rise against Blaise Compaore, who has been in power for 27

years and was trying, by a vote in parliament, for another five.

Though some see Sankara as an autocrat who came to office by the power of

the gun, and who ignored basic human rights in pursuit of his ideals, in

recent years he has been cited as a revolutionary inspiration not only in

Burkina Faso but in other countries across Africa.

In the weeks before

<http://www.aljazeera.com/news/africa/2014/10/burkina-faso-president-refuses

-step-down-201410312021512407.html> the current chaos, Al Jazeera spoke to

people in the capital, Ouagadougou, and found many who predicted that

Sankara’s memory, and Compaore's attempt to seek another five-year term, may

soon spark an uprising.

At the time of his assassination Sankara was just 37 and had ruled for only

four years.

But his policies, and his vision, are still cherished both by some locals

who were around when he was in power and, significantly, by many young

people who were born since his death.

His killing was the the fifth coup since the nation won independence from

France and the main beneficiary was Compaore, who quickly took his place.

Until that night, the two had often been referred to as best friends.

Although there is less poverty now than back then, a growing number of

Burkinabés had, in recent years, started to feel that Sankara's

nationalisation policies may have made the perpetually arid nation a more

prosperous and self-reliant place than it is today.

"Sankara wanted a thriving Burkina Faso, relying on local human and natural

resources as opposed to foreign aid," retired professor of economics, Noel

Nébié, told Al Jazeera.

"And starting with agriculture, which represents more than 32 per cent of

the country's GDP and employs 80 percent of the working population, he

smashed the economic elite who controlled most of the arable land and

granted access to subsistence farmers. That improved production making the

country almost self-sufficient."

Naming a nation

Initially known as the Republic of Upper Volta, after the river, in 1984

Sankara changed the country's name to Burkina Faso, meaning Land of the

Upright People, and he soon made that name the symbol of his nationalisation

crusade.

Some say the fact he authored his nation's name has kept his memory alive.

"When you wake up in the morning and you remember you are a Burkinabe, you

automatically recall the person who thought up that local name and stamped

it on us," Ishmael Kaboré, a 47-year-old lawyer in Ouagadougou, told Al

Jazeera.

"At first, people felt the name Burkina Faso was odd, awkward and far from

the modern and foreign names other countries were bearing in Africa.

"But they realised after his death that Sankara wanted to give us a unique

and special identity that tells our history and depicts our character."

Sankara was a determined pan-Africanist, whose foreign policies were largely

centred on anti-imperialism. His government spurned foreign aid and tried to

stamp out the influence of the International Monetary Fund and the World

Bank in the country by adopting debt reduction policies and nationalising

all land and mineral wealth.

Self-sufficiency and land reform policies were designed to fight famine, a

nationwide literacy campaign was launched, and families were ordered to have

their children vaccinated.

"Some families used to keep their children in hiding on the arrival of

vaccinators for religious or ritual reasons, and that practice was

sabotaging our efforts," Fatoumata Koulibaly, assistant campaign director at

the country's health ministry under Sankara, told Al Jazeera.

"But when Sankara came he took a strong stand against it, which helped in

the vaccination of close to three million children against meningitis,

yellow fever and measles, etc."

Vaccination has been common practice in Burkina Faso since then, she said.

Anger bubbles up

Sankara was often referred to as "Africa's Che Guevara" because he regularly

quoted, and said he drew inspiration from, the world famous revolutionary

leader. Sankara was also a good friend of former Ghanaian president, and

fellow revolutionary, Jerry Rawlings.

Even for his most ardent of supporters it is impossible to know whether, if

Sankara had not been killed, life would have been better, and some argue

that it would not have.

But many people spoken to by Al Jazeera believed things would be better

today if he was still alive, and that sentiment is partly responsible for

Thursday's events.

"Young people who were not alive during Sankara’s administration are

beginning to look back more at that period because something is wrong in the

country today," 23-year-old University of Ouagadougou student, Ibrahim

Sanogo, said.

"Sankara was not just fighting imperialism for the sake of politics but he

wanted the Burkinabe people to develop themselves and their land and rely

essentially on themselves instead of the West.

"Today, all the young graduates are dreaming to travel abroad to do odd jobs

because of lack of employment opportunities here."

Compaore, though, has had some success. The mining industry has seen a boost

in recent years, with the copper, iron and manganese markets all improving.

Gold production shot up by 32 percent in 2011 at six sites, according to

figures from the mines ministry, making Burkina Faso the fourth-largest gold

producer in Africa.

Growth is running at seven percent. But per capita income stands at just

$790, and local people say the standard of living is very poor for most.

Corruption and elitism are a problem, they say, with any wealth only in the

hands of the few.

"Those World Bank and IMF figures are seen only on paper and not in the

pockets of the Burkinabes," Seydou Yabré, an independent rural development

expert, told Al Jazeera.

"Only very few people are enjoying the wealth of the country. If you visit

homes, or travel to the hinterlands, you will experience an appalling level

of poverty."

Eerie prediction

Perhaps Sankara's anti-corruption campaign and exemplary modest lifestyle

could have forced wealth to trickle down if he had been left alive to lead,

Yabré thought.

"Sankara was Africa’s most down-to-earth president then. He lived in a

small, modest house, rode a bicycle and had $350 in his account at the time

of his death," Yabré said.

"He was also contested within his inner circle because he never wanted his

army colleagues to embezzle public funds and lead a flamboyant lifestyle."

Famously - and eerily - just a week before his death, perhaps sensing what

was to come, Sankara said: "While revolutionaries as individuals can be

murdered, you cannot kill ideas."

Burkina Faso’s progress over the past 20 years was largely due to its

stability, many observers say, but, as was made clear when a crowd of the

country's people converged on the parliament intent on destruction, an anger

left to fester can take that away in an instant.

"Sankara had many enemies because he wrested privileges from looters in

favour of the poor," Yabré said. "Maybe he did this too radically and within

too short a time."

Follow Kingsley Kobo on Twitter: <https://twitter.com/KoboKingsley>

_at_KoboKingsley

http://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2014/10/30/2014103018146450734_20.jp

g

At the time of his murder Sankara was just 37 and had ruled for four years

[La Vie de Sankara in Ouagadougou]

(image/jpeg attachment: image003.jpg)