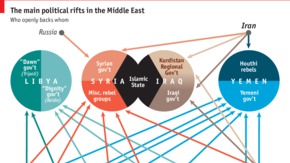

THE war in Yemen is the archetypal quarrel in a faraway country between people of whom the world knows nothing. Sometimes, though, its internal power struggles become enmeshed in wider geopolitical contests—rarely to its benefit. In the 1960s the rivalry between monarchists and Arab nationalists split the Arab world. Egypt intervened on the side of the nationalist republicans against the loyalists of the Zaydi imamate, backed by Saudi Arabia. These days the great division is the rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran, which feeds sectarianism between Sunnis and Shias respectively. Now Saudi Arabia and Egypt are allies, intervening to support Sunnis against the Houthis, a northern Zaydi militia, that is backed by Iran.

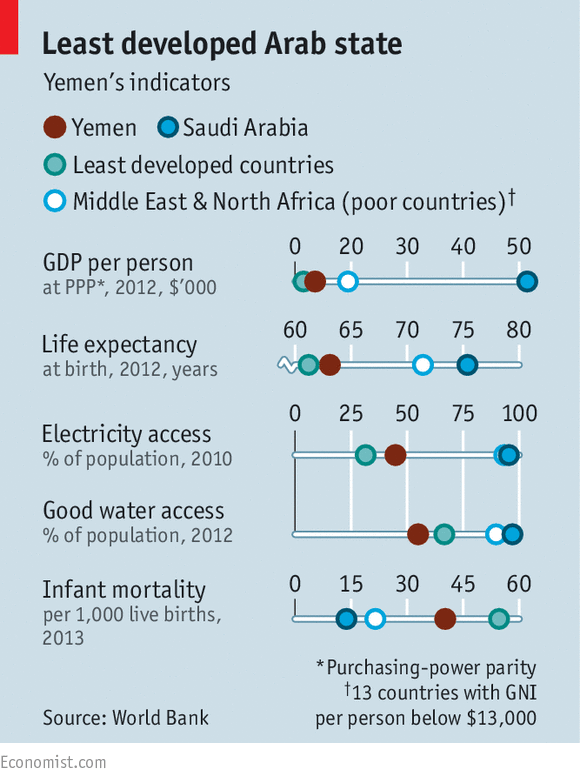

Three weeks into the air campaign, and with civilian casualties growing, there is little sign that the Saudi-led coalition has much of a political or military strategy. The Latin name for the land, Arabia Felix (Happy Arabia) seems a mockery: the poorest country in the Arab world is being bombed by one of the richest.

For America, which backs the Saudi operation with logistical help and intelligence, Yemen presents two dangers: it is a breeding ground for transnational jihadists (al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula is the most dangerous of the group’s branches) and it offers Iran an opportunity to extend its influence and nurture a Shia ally that, some fear, might become akin to Hizbullah in Lebanon. Both risks are being exacerbated by the chaos.

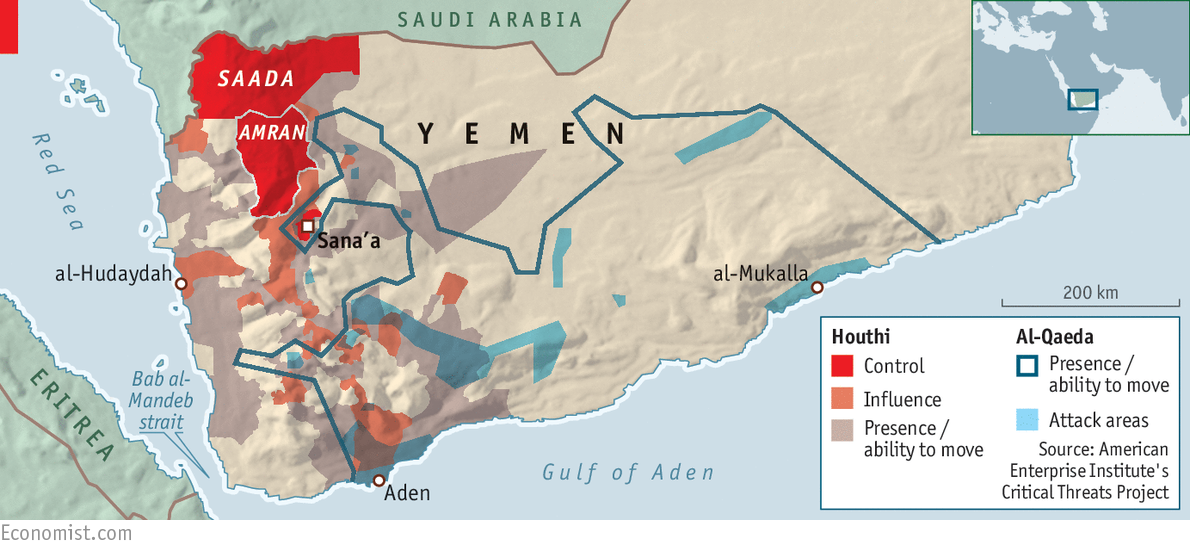

The Houthis fought repeated conflicts with the Yemeni government led by the former strongman, Ali Abdullah Saleh. Amid a popular uprising, the president stepped down in 2011 and power passed to a transitional government led by Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi. But the Houthis, now allied with Mr Saleh, took the capital, Sana’a, last September and then marched on Aden, to which Mr Hadi had fled.

Sectarianism has not been strong in Yemen, and there is much uncertainty about how much support Iran provides the Houthis. Rhetorically, though, Iran’s backing has become strident. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader, said Saudi attacks in Yemen amounted to genocide. In one tweet, he mocked the recently enthroned King Salman, and especially his son and defence minister, Prince Muhammad, who is in his thirties: “inexperienced #youngsters have come to power & replaced composure w barbarism”. Amid the chaos, al-Qaeda has taken over Mukalla, a Yemeni port—although it suffered a setback when an American drone strike killed one of its leaders on April 15th.

Saudi action might have prevented the Houthis from taking all of Aden, but they are still making gains. Air strikes alone will not defeat them, but the ground option is receding after Pakistan rebuffed a Saudi request to send troops (see Banyan). Egypt seems in no rush to send soldiers to Yemen, which some call its “Vietnam”.

Has the time come for a political deal? There are increasing calls for a ceasefire and negotiations. On April 14th the UN Security Council passed a resolution placing an arms embargo on the Houthis and Mr Saleh’s family. It also recognised the Saudi call for UN-mediated talks in Riyadh, a condition that no Houthi could agree to. In pushing for the restoration of Mr Hadi, the Saudis are relying on an unpopular ally, not least because he fled the country. Mr Hadi has appointed Khaled al-Bahah as his deputy. A former prime minister, Mr Bahah is seen as just about the only unifying figure in Yemen. Still, Saudi Arabia has set out no clear political objectives. That leaves it with the impossible task of trying to annihilate the Houthis—and allowing Iran to pose as the peacemaker.