Mussolini’s Italy brought death from the skies to East Africa in the 1930s – but left behind a striking futurist building in the Eritrean capital

Date: Sat, 18 Apr 2015 23:52:58 +0200

Asmara's Fiat Tagliero service station: a history of cities in 50 buildings, day 18

In 1935, the Italian air force launched chemical attacks on Ethiopian villages in the second act of a 40-year campaign to establish their Africa Orientale Italiana (Italian East Africa). The nightmarish vision of modern flying machines delivering death from the skies was a futurist’s dream – the perfect marriage of modernity and war, inseparable bedfellows and defining experiences of the 20th century. For Africa, encounters with modernity were particularly brutal but, amid the destruction they caused, there were remarkable examples of construction.

One of the most surprising legacies of this campaign was Asmara, the jewel in Italy’s former imperial crown and today the capital of Eritrea, Ethiopia’s northern neighbour. The Italians arrived in Asmara in 1889, but Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 transformed the sleepy colonial town into Africa’s most modern metropolis. Overnight, the skeletal form of a modern and brilliant urban plan, conceived in the 1910s by a particularly enlightened Italian architect-engineer Odoardo Cavagnari, was lavishly clothed in modernist architecture.

Sitting on its mountain perch 2,500 metres above the Red Sea, Asmara is an unlikely setting for a modernist urban idyll. Unlike other North African colonial cities appended to older urban settlements – Casablanca, Rabat, Mogadishu, Benghazi, and Tripoli – the Italians planned Eritrea’s modern settlements largely from scratch. Modern urban planning was liberally applied in Eritrea – for example, in Agordat, Assab, Dekemhare, Keren, and Mendefera – but the simultaneous experience of Italy’s conquest of Ethiopia and modernism’s global pre-war climax is what makes Asmara so special.

From 1935 until the allied defeat of Italy in 1941 (the allies’ first significant victory of the second world war), hundreds of buildings were designed by Italian architects and constructed by Eritreans in a variety of styles from modernism’s broad palette, including novecento, rationalism and futurism. Far from home, the imagination of Italian architects in Eritrea could run a little wild. The result was a startling collection of sumptuous cinemas, fantastical factories, stylish shops, beautiful bars and restaurants, plush hotels and abundant residences. Even government buildings exuded style. While Asmara’s renowned architectural character was derived largely from the geometric simplicity and aesthetic purity of rationalism (a specifically Italian brand of modernism), the city’s most remarkable structure, the Fiat Tagliero service station, is an unashamed tribute to futurism, an Italian artistic movement that had comparatively little architectural exposure.

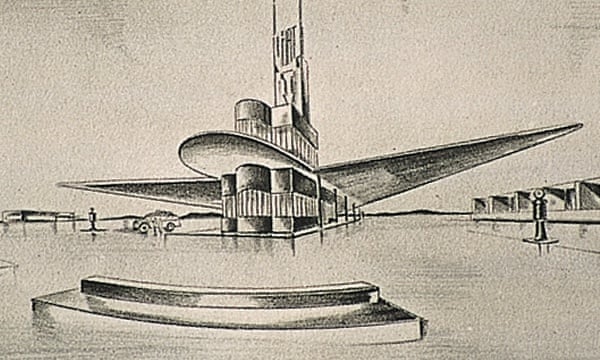

Futurism’s founding father, the Italian poet and theorist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, rejected the past and idolised speed, technology and war. Embodying these qualities in a colonial context, Fiat Tagliero was a monument to the aeroplane and a concrete reminder of the often-bitter universal experiences of the 20th century that shaped so many cities around the world. With its breathtaking 30-metre cantilevered wings, cockpit body and sleek wrap-around windows, Fiat Tagliero suits its surreal surroundings high above the clouds. Completed in 1938, the building was designed by Giuseppe Pettazzi months after Italian aeroplanes dispensed thousands of sulphur mustard shells and the asphyxiate diphenylchloroarsine (nicknamed mask-breaker by German troops in the first world war for its agonising effectiveness) killing tens of thousands of innocent Ethiopian civilians. These modern machines were even fitted with special vaporisers to enhance the chemicals’ dispersal. Protests to the League of Nations by Ethiopia’s Emperor Haile Selassie fell on deaf ears.

Futurism’s technologically inspired nihilism excited Italy’s fascists as much as Mussolini’s conquests in Africa excited the futurists. Marinetti’s Manifesto of Futurism in 1909 was an ode to war. In 1912, he reported from Libya during an earlier chapter in Italy’s empire building, writing: “War is beautiful because it initiates the dreamt-of metallisation of the human body.” In 1914 he was briefly imprisoned with fellow pro-war activist Benito Mussolini, whom he joined as a fascist electoral candidate for Milan in 1919. In 1935 he returned to Africa to witness Italy’s conquest of Ethiopia and to fuel his grisly artistic fascination.

Fiat Tagliero was built on a major intersection where any of Asmara’s 50,000 cars could stock up on petrol and supplies before departing the metropolis for the airport or Eritrea’s southern towns and Ethiopia beyond. Its location was strategic in the wider context of Italy’s new Roman Empire in Africa. Modern transportation helped define Italian colonialism and Eritrea was the hub linking other colonies of Somalia, Libya and Ethiopia. Airports in Asmara and Italy’s “Seconda Roma”, the modernist town of Dekemhare a few miles south of Asmara, plugged Eritrea into a fledgling international network of air travel. A breathtaking steam railway and marvel of Italian engineering recently restored by Eritreans wound its way tortuously from Eritrea’s Red Sea port of Massawa over the highlands and down towards Sudan. Eritrea even boasted the world’s longest cable car route, which delivered supplies directly from the coast.

Facing south on a busy junction with its wings aloft, poised for flight, Fiat Tagliero’s volant structure exemplified Eritrea’s colonial experience. The building’s audacious design stunned the sceptical municipal authorities. Unconvinced by the architect’s calculations, they insisted that the wings should be supported by columns. Technical drawings submitted to the municipality showing each wing propped up by 15 poles attest to the architect’s deception. However, at the building’s unveiling, Pettazzi is said to have put a gun to the contractor’s head and ordered him to remove the supports. Under duress, the builder complied and, to the astonishment of the crowd, the massive wings stayed up.

Still standing and recently refurbished, Fiat Tagliero has long since jettisoned its original associations and assumed a more progressive role as the symbol of the Asmara Heritage Project, which is applying to Unesco for world heritage status. Fascist-era buildings are not the most obvious candidate for representing “outstanding universal value”, but while Eritrea’s harsh encounter with modernity and war has caused untold misery, it has also bestowed on this small African nation a unique form of urbanism that post-independence Eritrea has made its own. It would be hard to find a capital city in Africa, or perhaps even in the world, that is so revered by its own people and visitors alike. In a country where aeroplanes were once synonymous with colonial suppression, Fiat Tagliero symbolises the quiet determination of Eritreans to protect their rich cultural heritage, forged over centuries by their country’s strategic position at the nexus of Africa, Europe and the Middle East.

Today, as global problems cause tens of thousands of Eritreans to risk their lives reaching Europe, the international community is desperate for solutions. Asmara’s Unesco bid is being supported by an enlightened international coalition that includes the British and Norwegian governments, who recognise the capacity of architecture, irrespective of its past, to effect positive change in the future. Fiat Tagliero is a fitting symbol of hope for a remarkable city.

Edward Denison is an architectural historian, writer and photographer specialising in 20th-century architectural and urban history. He also teaches architectural history and theory at the Bartlett School of Architecture (UCL). Click here to see more of Denison’s images from Eritrea.