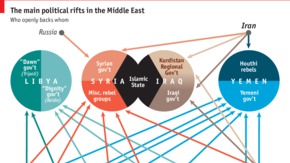

BY WADING into the war in Yemen, Saudi Arabia may well have made matters worse. Tension with its regional rival, Iran, has deepened. Saudi aircraft are said to have killed up to 400 civilians and destroyed scores of buildings. So most Yemenis—and Arabs across the region—sighed with relief when the Saudis said on April 21st that they would end their air strikes. Yet they reserved the right to continue, albeit on a more limited scale. The next day their jets hit a force of Houthis, members of Yemen’s Iran-backed Shia sect, who were fighting for an army base near Taiz, the benighted country’s third city.

The Saudis’ claim that their aims had been achieved rang hollow. They may have destroyed many of the Houthis’ heavy weapons. They see a victory in the UN Security Council’s resolution that puts an embargo on arms to the Houthis. But they are no nearer to stopping the advance of the Houthis alongside factions loyal to Ali Abdullah Saleh, the long-serving president, who was ousted in 2012. Nor are the Saudis able to reinstall their unpopular protégé, Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi, who replaced Mr Saleh but who is in exile in the Saudi capital, Riyadh.

There are rumours of a secret deal between Saudi Arabia and Iran to stop the Saudi air raids on Sana’a, Yemen’s capital, which the Houthis captured last year, in exchange for letting the strikes continue in parts of the south, for instance in Taiz, where Sunnis are in the majority. Iran was quick to praise the end of Saudi air attacks.

America appears to have played its part, too, with President Barack Obama leaning on King Salman to ease up. The Americans, along with Arab members of the Saudi-led coalition, are afraid of the war spinning out of control. Along with civilian deaths in the Saudi air raids, much of Yemen’s decrepit infrastructure, including the health service, has collapsed. Humanitarian agencies say the Saudi-led operation has blocked aid. Oblivious to the unfolding humanitarian crisis, Prince Alwaleed bin Talal, a billionaire member of the royal family, made a tin-eared offer. He said he would donate 100 Bentley cars, giving one to each of the Saudi fighter pilots participating in the campaign.

Yet Saudi policy is hard to predict. It is driven not only by its rulers’ dislike of Iran and by a sense that Yemen is the kingdom’s backyard. Salman, who acceded only in January, is also acutely aware that the war’s outcome will affect his own standing and that of his favoured son, Muhammad, who some say is being positioned for a bid, in due course, for the succession. He already holds two powerful posts, as chief of the royal court and as defence minister.

America has sent a second warship off Yemen’s shores, supposedly to protect shipping lanes but more likely to deter Iranian ships from delivering arms to the Houthis. This may reassure the Saudis that, even if they stop bombing from the air, the Houthis will not be able to replenish their supply of arms from Iran by sea.

The Houthis still control Sana’a, and Mr Hadi’s allies have pledged to battle on. So the fighting is likely to continue. Many Yemenis fear that the Saudis will now finance Sunni proxies.

So Yemen’s chaos is likely to continue, whatever the Saudis do. The Houthis’ demands for a major say in any government of national unity seem unlikely to be met by their Saudi-backed opponents. Many southerners want secession. And al-Qaeda controls an expanding slice of territory in the south and east.