DESPITE the Middle East’s bloody reputation, most of the region’s generals have been able to kick off their boots for much of the past few decades. Apart from a few gruesome interludes, such as Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait or the nearly decade-long war it fought with Iran in the 1980s, the major Arab powers have not had to do much fighting since reaching peace deals or durable ceasefires with Israel after the war in 1973.

Yet all armies in the region were forced to shake off their torpor after the uprisings of the Arab spring of 2011 and the conflicts that they sparked. Now it is hard to find many that are not fighting. Their foes range from Islamic State (IS) in Syria and Iraq to the Iranian-backed Houthi militias in Yemen. (And, in several worrying cases, their own civilians).

With America and Europe reluctant once again to commit ground forces to the region, its stability will depend to a large degree on the fighting ability of the Arab armies. Are they up to the job?

Going on their past performance there is little reason for hope. In previous decades big Arab armies were trounced by Israel, and fared little better against Iran or in excursions into African countries such as Chad. Today, even with Western arms and support, many struggle to hold their ground when bullets start to fly. Large parts of Iraq’s national army, despite having received billions of dollars in training and equipment from America, disintegrated last year when small forces from IS took Mosul and swathes of the country. Put to the test at home, the armies in Yemen and Libya have simply splintered. Lebanon, whose army in any case only has dominion over part of the country (see article), is struggling to stop the mayhem in Syria from crashing over the border.

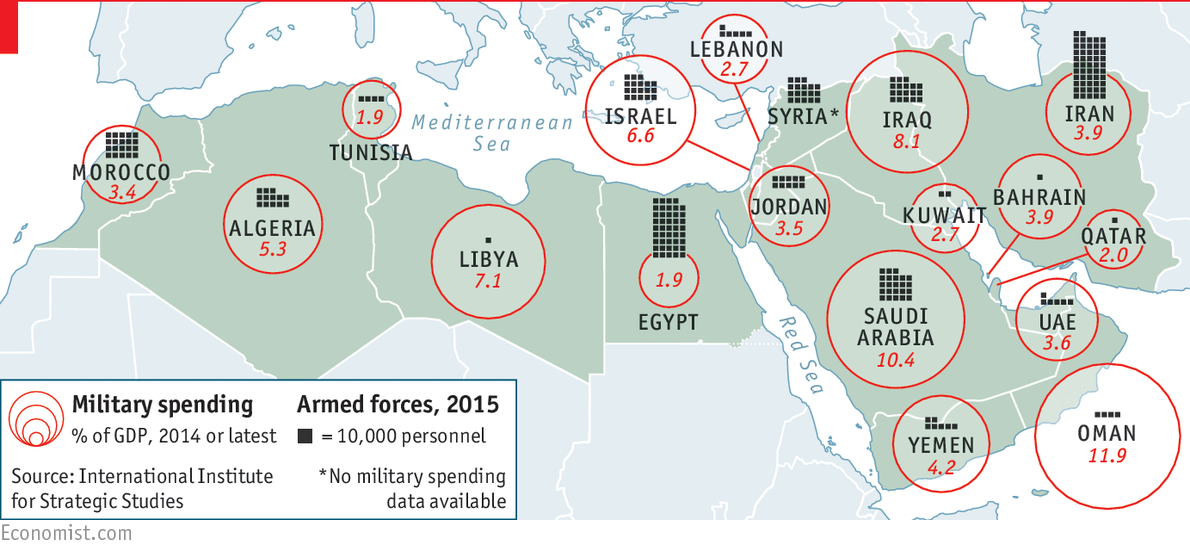

Arab armies’ problems certainly do not stem from want of money or equipment: the region’s countries allocate hefty shares of GDP for their forces (see map). The International Institute for Strategic Studies, a think-tank in London, reckons that countries in the Middle East and north Africa make up eight of the top 15 spenders on defence when measured as a share of the national pie.

One problem is that much of this money is wasted. Billions are splurged on flashy gear like jet fighters or submarines that look impressive but may not be appropriate to the kinds of conflicts they are fighting. Such toys are also hard to maintain. And widespread theft and corruption mean that a lot of kit disappears, or is kept in the barracks (which is one reason why IS was able to nab so much in Iraq).

Less priority is given to command and control, logistics and intelligence-gathering. Plans lack flexibility and are adhered to even when they don’t work. That is exacerbated by the lack of authority given to junior and non-commissioned officers, the glue in most Western armies. Their deference to seniority is the norm in Arab society, but leaves small units unable to act quickly without waiting for approval.

An even more serious weakness is that armed forces in the Arab world simply don’t function as neutral, professional institutions like their Western counterparts. They are often more loyal to a ruler or an ethnic or religious community than to the state: Syria is an example of the former, Libya and Yemen, riven by tribal and regional loyalties, of the latter. Military men are big players in the economies and politics of countries such as Egypt—ever more so since states have tottered after 2011. The turnover of senior officers is high since regimes fear them as potential coup-plotters.

To cope, many countries outsource military tasks to militias. Bashar Assad, Syria’s despot, pays multiple groups to fight for him; countries that want him out support rebel groups. In Iraq the government and its ally, Iran, pay Shia militias to battle IS.

Yet there is an alternative to simply handing over the protection of the state to armed gangs. Jordan and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) are by no means first-rank military powers, but they are among the region’s most modern and capable. Their air forces are competent; their elite units well-trained. Jordan has particularly good special forces thanks to a bespoke training facility that regularly hosts visiting contingents from elsewhere (many of whom compete in an annual “Warrior Competition”). In general the region’s counter-terrorist and special forces have proved adequate. Some have established the esprit de corps that makes for effective fighting units. But this small number of elite troops is generally overburdened, as they are sent from one trouble spot to another.

The UAE’s conventional forces, meanwhile, have proved their—relative—worth in Yemen: since landing in Aden this month they have made rapid progress against the Houthis. That is in contrast to the force committed by Saudi Arabia, which has made little headway.

If Arab armies are to be a bulwark against the spread of IS and other militias they will need deep reform. The first step would be to shrink them. Many are bloated with poorly educated and badly paid troops. Egypt counts 438,500 men on active duty; Saudi Arabia, 227,000. That is partly because they have been used to mop up unemployed young men. The result in Syria and Egypt is boys who are underpaid, underfed and treated as cannon fodder—and perform as such. “If you think you’re likely to run out of bullets or if you get injured there won’t be good medical care, you are less inclined to fight,” says Lord (David) Richards, the former head of the British armed forces.

Smaller, professional forces composed of educated and well-paid recruits would likely prove more effective in battle, but few governments in the region are willing to raise these sorts of armies because they fear coups. If they are to improve their performance on the battlefield, Arab states will also have to improve their governance at home.