Date: Tue, 2 Jun 2015 23:48:14 +0200

Sectarianism in the Middle East

The U.N.-administered camp at Mazrak, northwest Yemen is now stretched beyond capacity after a Saudi military offensive against the Houthis starting early November uprooted a fresh wave of IDP families. (Photo credit: Hugh Macleod/IRIN)

Yemen had drawn little attention in the United States, or in many other parts of the world, until recent events thrust it into the headlines. It has an arguably strategic location on the Bab e-Mandeb, the strait controlling access to the southern end of the Red Sea (and, ultimately, the Suez Canal), and still it managed to remain ignored.

Yemen is the poorest country in the Arab world. Although much smaller geographically, its population is nearly equal to that of neighboring Saudi Arabia. It has a little oil, discovered only in the 1980s, but it is already running out. It has a little water; that is running out as well. Remittances from Yemenis working abroad are a major source of revenue.

For a while, it was two countries: Yemen (sometimes called North Yemen) and South Yemen. North Yemen suffered a civil war in the 1960s, after the army overthrew the monarchy and declared a republic. Nasser’s Egypt intervened to support of the new government’s fight against the traditionalist tribes of the north (northern North Yemen), who remained loyal to the royal family. This came to be known as Egypt’s Vietnam. Egypt cut off its participation after defeat in the Six-Day War (1967) forced it to change its priorities.

South Yemen grew from the British protectorate of Aden, which was granted independence as a separate country in 1967. South Yemen became a Soviet client state and still did not manage to attract much attention. In January 1986, a brief civil war erupted there among rival factions of the ruling party. (It actually began with a shootout at a politburo meeting.) In less than two weeks, the conflict had killed up to 10,000 people, including much of the political elite.

South Yemen never really recovered, and in 1990 it voluntarily merged with North Yemen to form today’s Yemen. While the North’s government considered this a natural outcome, a number of South Yemenis resented it. Yet another civil war, started by southern separatists, erupted in 1994, and separatist sentiments persist in the south to this day.

Thus, the fact that there is fighting in Yemen today is tragic but not really novel. Today’s conflict brings a complex array of old and new actors to the scene. It is often portrayed as a proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran and as part of a greater struggle between Sunni and Shiite Muslims, but that is a distortion. Saudi Arabia and Iran do play key roles in the conflict, and their action affect the calculations of internal players, but no one in Yemen is fighting on behalf of either of them and the fight is not about religion. Who are the leading players in today’s drama?

The Houthis

The Houthis are not so much an organization as a clan — or at least a clan-based organization — from the northern province of Sa’dah. Traditional in their ways and highly chary of their independence, they formed the backbone of the 1960s rebellion against the military regime, and they have rebelled against the government of the united Yemen a half dozen times in just the past 15 years.

Religiously, the Houthis are Zaydis, or Fiver Shiites. Fivers were once the predominate branch of Shiism, but then, in the 16th century, the Safavid dynasty made Twelver Shiism the official state religion of Iran. Now the Shiites of Iran, Iraq, Bahrain, and Lebanon are Twelvers. Fivers are prominent only in Yemen, where they constitute at least two-fifths of the population. The original split between the Fivers and the Twelvers was rooted in a dispute over how many of Muhammad’s successors were true Imams. Theologically, the Fivers are probably as close to the Sunnis as they are to the Twelver Shiites of Iran, but today’s conflicts and alliances have little to do with theology. Fivers do, however, say they have a religious obligation to oppose unjust rule.

Although the Houthis have some (frankly, offensive) Iranian-inspired slogans, they are fighting for their own issues, namely against corruption and what they view as an overbearing central government. They do not appear to take direction from Tehran, and they accept Iran’s support because Iran offers it and no one else does. In fact, last September, they seized Yemen’s capital despite Iranian efforts to dissuade them.

Iranian support in the country is a way to annoy and distract Saudi Arabia. In the 1960s, however, when secular-socialist pan-Arab Nasserites were seen as the main threat, it was actually Saudi Arabia that armed and supported the Houthis. The Houthis have offered to cooperate with rival factions a number of times. They did not immediately depose the government when they seized the capital in September 2014, but merely forced themselves into the ongoing debate over a new constitution, from which they had been excluded.

On the other hand, they are not particularly skilled at cooperation. At one point, when they failed to get their way in the constitutional talks, they kidnapped the president’s chief of staff and threatened to hold him hostage until the government conceded the point. Eventually, they did put the president, prime minister and cabinet under house arrest. Once in power, they became more dictatorial, embodying the qualities they claimed to be fighting against. In February, al-Hadi escaped to Aden and proclaimed himself president again, and the current stage of the fight began. The Houthis began advancing to the south, and in March a Saudi-led coalition began their bombing campaign in support of al-Hadi.

Ali Abdullah Saleh

Ali Abdullah Saleh became president of North Yemen in 1978 and was the only president that the united Yemen knew until 2012. Like the Houthis, he is technically a Zaydi, but he is of a more Westernized variety, a secular nationalist at heart. The Houthis rebelled against his rule repeatedly. Although widely viewed as corrupt and a poor administrator, Saleh is highly adept at playing factions off one another.

After the rise of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), Saleh permitted the United States to conduct drone attacks against the group. He also enjoyed increased military assistance from the United States, but he focused his own military efforts against the Houthis rather than AQAP. He viewed the Houthis as the greater threat to his own rule — a position vindicated by recent events — and, according to some analysts, he did not want to defeat AQAP outright. The new support that he was receiving from the United States was a direct result of AQAP’s presence in his country, and he understood that the United States would lose interest and turn its attention elsewhere if the group were actually eliminated. The Houthis have been much more vigorously anti-AQAP than Saleh.

In 2011, during the so-called Arab Spring, massive demonstrations formed in the capital, demanding that Saleh leave. A central city square was occupied for months. The demonstrators, mostly students in the beginning, attracted a broader cross section of society. A rival family, al-Ahmar, from Saleh’s tribe split with him. The army divided, with some units remaining loyal to Saleh personally and others to the al-Ahmar family. Houthis launched attacks against the presidential palace. Saleh was seriously injured by a bomb. With the prospect of civil war growing, the Gulf Cooperation Council mediated a solution. Saleh voluntarily stepped down and his vice president, Abd Rabbuh Mansour al-Hadi, a southerner, was “elected” in an election in which he was the only candidate.

Saleh, however, was not finished. Key units of the military remained loyal to him, even out of office. After the Houthis seized the capital in 2014, Saleh made common cause with them against al-Hadi, despite the fact that they had rebelled against him six times. He brought with him the elite divisions of the army and the entire air force. This is what allowed the Houthis to move so swiftly into southern Yemen after al-Hadi fled to Aden.

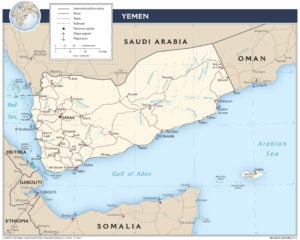

Today’s Yemen was formed from the merger of the former Yemen (North Yemen)and South Yemen (much of which lies to the east). (Map: CIA)

Saudi Arabia

The Saudis are backing the forces of President al-Hadi with aerial bombardments, but they are not popular on either side of the Yemeni divide. They have depicted the Houthi advances as an Iranian maneuver to encircle the Arab heartland. They are also concerned that a Houthi victory could inspire Saudi Arabia’s own Shiite minority. (Saudi Arabia’s Shiite minority and its oil deposits are both concentrated in its Eastern province.) They have apparently intervened for these reasons.

The new Saudi king, Salman bin Abd al-Aziz, came to the throne in January of this year, upon the death of his brother. He named his son, Muhammad bin Salman, minister of defense and deputy crown prince. Muhammad bin Salman, who is 29 years old and has neither military experience nor a military education, has become the public face of the Yemeni war within Saudi Arabia.

The Pakistanis, who were invited to participate in the Saudi-led coalition but refused, have described Saudi Arabia’s intervention as a panicked reaction to local events. They also say that the Saudis have no plan for victory. Saudi Arabia’s reputation for being cautious and risk-averse is giving way to a new reputation for being impulsive and rash.

The United States has pressed the Saudis to halt their air campaign for fear of triggering a larger regional conflict, but it has also enabled the campaign by providing logistical, material, and intelligence support. The latter probably reflects a perceived need to bolster relations with Saudi Arabia given Saudi suspicions that U.S. negotiations with Iran over the latter’s nuclear program might reflect some sort of pro-Iranian shift in U.S. policy toward the Middle East.

Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

AQAP is viewed as the most dangerous member of the network of local al Qaeda affiliates. The group operates primarily in the eastern regions of the former South Yemen. It was formed in January 2009 through the merger of al Qaeda’s Yemeni and Saudi affiliates. The Saudis, having been crushed and pushed out of their own country, merged with and revitalized the Yemeni group. AQAP has focused primarily on local issues and enemies, like other al Qaeda affiliates, but over the years it has expanded into the broader international arena to an unusual degree. It was behind the failed “underwear bomber” over Detroit in 2009, another failed attempt to destroy an airliner in 2010, and the attack on the Charlie Hebdo editorial offices in Paris earlier this year. The group publishes an English-language online magazine for terrorists. Still, its primary focus has remained local.

AQAP has not been a principal player in the fight between the Houthis and the forces of President al-Hadi, but it has benefited from the disruption. It has taken advantage of the chaos to extend its area of control, and it has forged new alliances with Sunni tribes, including some that actively fought it in the past, that object to the expansion of Houthi control.

The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria

The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), sometimes called the Islamic State, is the newest newcomer to the cast. It has announced a presence in Yemen only since the beginning of the current fighting. The group’s suicide bombers have attacked a Zaydi mosque in Yemen as well as a Shiite mosque in Saudi Arabia. This is in an apparent attempt to fuel further sectarian violence in the region. So far, ISIS has thrived only in places already wracked by war and political chaos.

What Future?

More bombing is not what Yemen needs. Unlike ISIS in Iraq, the Houthis are deeply rooted in Yemeni society, or at least in a portion of it. The bombing will most likely escalate the conflict, driving the Houthis closer to Iran, which is the opposite of the outcome that the Saudis want. A preferable approach would be to neutralize the Houthis as a threat. Reconciliation in a broad-based government will be difficult — there is a great deal of mistrust, and U.N.-sponsored efforts have made little headway — but the longer it is delayed, the more difficult it will become.