Date: Fri, 5 Jun 2015 23:17:25 +0200

By Ahmed Kodouda

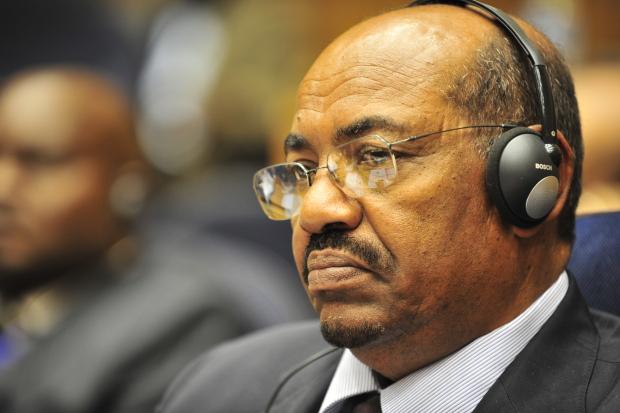

After a quarter of a century in power, Omar al Bashir’s regime has never been more stable internationally. Despite domestic unrest, as armed conflicts rage on three fronts and an economic malaise threatens the country’s viability, the ruling National Congress Party (NCP) has been able to survive one of the most volatile periods in the region’s history. The regime – built on a shaky alliance between Bashir, the Islamic Movement and influential business interests, protected by national security organs and buttressed by the military – is stronger than ever.

Bashir has been able to overcome bigger obstacles than those that toppled his predecessors in 1964 and 1985. The threats are both domestic and international. They range from civil wars, economic stagnation and challenges from within his own rank-and-file, to the political danger brought by a young population yearning for change. Internationally, the regime continues to experience tough sanctions resulting both from its history as a regional sponsor of terrorism, and the mass atrocities committed by government in Darfur, South Kordofan and Blue Nile.

For a regime to survive so long, long-term strategy must be subordinate to short-term pragmatism. In order to neutralize any threat from outside, it must, as this regime continues to, interfere with and destabilize its neighbours. Moreover, the regime must, and continues to, navigate rough international waters and sell its allegiance to the highest bidder, irrespective of the country’s benefit or interests.

In October 2014, Bashir arrived in Cairo as an ally of the Islamists forces in control of Tripoli (Libya’s western capital), and returned to Khartoum as an ostensible supporter of the internationally-recognized government in Tobruk. In late March 2015, Bashir arrived in Riyadh as Iran’s only Sunni ally and returned to Khartoum as one of its many enemies, participating in the Saudi-led “Decisive Storm” offensive in Yemen. It sold out its long-time ally Iran when the Gulf States tightened the economic noose, cutting vital economic aid and halting bank transfers into Sudan.

Regionally, Sudan is surrounded by conflicts and unrest. Civil wars are being waged in nearby South Sudan, the Central African Republic, northern Nigeria, Libya, Somalia, and as far away as Iraq, Syria and Yemen.

During a visit to Washington in February, Ibrahim Ghandour, Bashir’s top adviser and emissary, was reported to have told the Obama administration that Sudan is “an island of stability in an ocean of instability”, and that Khartoum should be seen as an ally to bring calm to this chaotic part of the world.

The reality is quite the opposite, as Khartoum – by necessity and for its own survival – has a hand, in one way or another, in all of these aforementioned conflicts – despite the distance between Sudan and some of these wars. It is important to note the regional context, as none of Sudan’s immediate neighbours have much experience of democratic governance or institutions.

The region has a long history of neighbours interfering in each other’s affairs, as was the case between Chad and Sudan in the 2000’s and Libya under Gaddafi in Darfur, for example. Rather than “an island of stability,” Khartoum is in fact interested in, and a major source of, instability in its own neighbourhood. Khartoum’s involvement in regional affairs is a litany of deleterious interference and meddling.

In South Sudan, Khartoum has been accused of arming rebel forces fighting the government and providing logistical support and intelligence to proxies throughout the region. The best evidence of this comes from the Small Arms Survey, a research group, which has extensively documented the use of Sudanese-made munitions in South Sudan.

Of course, the regime has a long and well-tested experience of perfecting its divide-and-rule strategies during the civil war in the south, before separation. Although Khartoum continues to position itself as a peacemaker in South Sudan by hosting Chinese-facilitated talks between the two warring sides in January 2015 and playing a role in the IGAD mediation process, its interest is in the continuation of the war, as long as the flow of South Sudanese oil – which amounted to a precious $880 million in 2014 – is not threatened.

If South Sudan is too busy fighting itself, it won’t be able to support armed groups in Sudan, especially the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-North (SPLA-N), a vestige of the SPLA which now runs South Sudan. Sudan doesn’t necessarily want South Sudan to implode, but many in Khartoum feel vindication and glee as the war rages, seeing it as an opportunity to play all sides of the conflict to their advantage.

In the Central African Republic, Sudan has been accused of arming and supporting rebel groups since 2007 and has fueled the recent – religiously-motivated – civil war by providing arms to the Muslim Seleka rebels. According to Conflict Armament Research, the Seleka have stockpiles of Sudanese small arms munitions manufactured as recently as 2013 and have used Sudanese-made light tactical vehicles.

In Libya, Khartoum is alleged to be backing Islamist forces fighting the internationally recognized government, despite promising to do the opposite after Bashir’s aforementioned October 2014 visit to Cairo. In 2011, Bashir boasted about his government’s central role in funneling arms to rebels during the civil war that toppled Muamar Gaddafi, who played a similarly negative role in destabilizing the region.

In Egypt, Sudan’s involvement was most brazen, when in the mid-1990s, Khartoum’s National Intelligence and Security services in cooperation with Egyptian militants allegedly orchestrated an assassination attempt against former President Hosni Mubarak in Addis Ababa. Today, it is accused of harboring fugitive members of the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood. Khartoum also has a long history of supporting the Lord’s Resistance Army operating in Northern Uganda, South Sudan, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Central African Republic.

In Yemen, the regime is trying to shore up its “stabilizing” credentials by participating in the Saudi-led ‘Decisive Storm’ coalition against the Houthis. However, Port Sudan was a key base for Iranian warships that funneled weapons to the Iran-backed rebels.

In Syria, Khartoum was accused of arming rebels fighting Bashar al Assad in 2013, while maintaining very close, friendly ties with the Syrian regime’s closest ally, Iran. Moreover, on several different occasions, the country, including Khartoum itself, was bombed by Israeli warplanes because the regime hosted Iranian weapons industries and established corridors to smuggle weapons to Hamas in Gaza.

Some of the radical Islamist members of al Shabab in Somalia and Boko Haram in Nigeria were educated in Khartoum’s International University of Africa, a hotbed for Islamic radicalization. In fact, during a recent televised interview, Bashir claimed that half of the individuals that made up the various transitional governments in Somalia over the past quarter century were educated and “raised” in Sudan.

Sudan was also accused of harboring Islamist militants who fled Mali after the French and African Union counter invasion in 2013, something that it has strenuously denied by Khartoum. The regime certainly hosted international terrorists such as Osama bin Laden and Carlos the Jackal during its early years. Most alarmingly, Sudanese munitions were recently reportedly used by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which unlike other terrorist groups, has territorial ambitions and has recently expanded into Libya.

Khartoum’s meddling beyond its borders is often times opportunistic, with little long-term vision or strategy. However, central to its approach is the regime’s primary tool for destabilizing the region: its robust Military Industry Corporation, a government-owned producer of arms, munitions and vehicles. Sudan is the third largest arms producer in Africa after Egypt and South Africa, providing arms and munitions both state and non-state actors.

It is also the first transit point for Chinese and Iranian weapons destined for other, often unstable or war-torn, African countries. Khartoum’s military industry has a surprisingly long reach, as Sudanese-made munitions were found in Ivory Coast in 2009, when that country witnessed civil unrest , even though Sudan does not seem to have any strategic interests in that part of the world.

Despite international arms embargoes and sanctions, the regime has no qualms about flaunting its arms industry, as in February 2015, when Sudan had one of the largest delegations at the International Defense Exhibition and Conference (IDEX) in the United Arab Emirates of any African or Middle Eastern country. Bashir was the only head of state present during the opening ceremony. According to the Small Arms Survey, this large showing at IDEX is proof of Khartoum’s ambitions of attracting global arms purchasers, not just from its own neighborhood.

Finally, the “island of stability” analogy falls short as soon as we look domestically, as armed conflicts rage to various degrees in Darfur, South Kordofan and Blue Nile, and the regime’s divide-and-rule tactics are tearing the fabric of the society apart. According to the United Nations, 5.4 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance in the country. In Darfur, the government has all but lost control, as the conflict between various armed groups, tribal militias, parastatal militias and the government’s own regular forces displaced 430,000 people in 2014 – more than any year since the conflict began in 2004 – and some 100,000 people were displaced in January 2015 alone.

As a result, the African Union, the United Nations and the entire international community must take Khartoum’s rhetoric with a huge grain of salt. Sudan is not an island of stability in a chaotic region, but rather a nation slowly collapsing while serving as a hub for regional instability and chaos.