Date: Sat, 6 Jun 2015 00:41:47 +0200

Smoke rises from al-Qahira castle, an ancient fortress that was recently taken over by Shiite rebels, as another building on the Saber mountain, in the background, explodes after Saudi-led airstrikes in Taiz city, Yemen, on May 21. (Abdulnasser Alseddik/AP)

In Syria and Iraq, the Islamic State's wanton vandalizing and looting of antiquities has rightfully led to horror around the world. But those sites may not be the only cultural sites in the Middle East facing destruction.

In Yemen, where Houthi rebels are fighting pro-government forces and a Saudi-led coalition, there have been numerous reports of irreplaceable sites being damaged by violence, too, even if they have failed to spark the same outrage.

On Thursday, for example, the Yemen Post tweeted images of the centuries-old al-Qahira castle apparently being hit by an airstrike. The castle was "destroyed," the local outlet stated.

It is unclear whether the castle has actually been destroyed or what the level of destruction at the site amounts to. The photographs shared by the Yemen Post appear to date back to May.

The news outlet had previously reported that the site, also referred to as Cairo Castle, had been targeted by airstrikes because of its use by Houthi rebels. Photographs shot by AP photographer Abdulnasser Alseddik show smoke billowing from the castle on May 21.

Even from the images above, it's easy to see why al-Qahira castle is considered a landmark worth preserving. It commands a strategic position atop a hill overlooking the southern city of Taiz, Yemen's third-largest. Exactly who built the castle is disputed, since it has been destroyed and rebuilt many times over the years – some say its original construction predates the arrival of Islam in Yemen in the 7th century AD, while others date it to the 10th century. It had been undergoing a renovation in recent years.

Al-Qahira is far from the only site at risk. Earlier this week, local outlets and social media reported that the Great Dam of Marib had been damaged in airstrikes. Speaking to National Geographic, Iris Gerlach, director of the Sanaa Branch of the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), confirmed that the airstrike appeared to have targeted a better-preserved area of the dam.

The dam, considered one of the most important ancient sites in Yemen and the oldest dam from its era currently surviving, dates back to at least the 8th century B.C. It was built upstream from the ancient city of Ma'rib, once the capital of the Kingdom of Saba (the biblical land of Sheba).

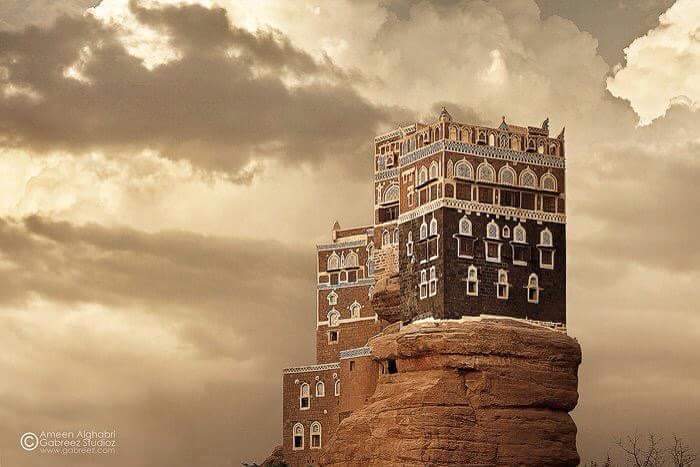

More cultural sites still are in jeopardy. On Thursday there were unconfirmed reports on social media that Dar al-Hajar, a former summer palace for Yemen's royals near the capital, Sanaa, that has become an impressive tourist attraction, had been hit by an airstrike. Thankfully, later social media reports suggested the building had been missed by a few yards.

The reports of damaged sites goes on and on. UNESCO said in May that the Old City of Sana'a, a World Heritage site, had been bombed, and that the Old City of Saa'dah, on Yemen’s World Heritage Tentative List, had also been damaged in strikes. The 1,200-year-old al-Hadi Mosque, one of the oldest Shiite religious centers on the Arabian Peninsula, has been razed by airstrikes, according to Reuters, as has the Dhamar Museum, a repository of ancient artifacts for the region.

Pix of Dhamar museum before and after being hit by Saudi two days ago. Dhamar province of S #Yemen

UNESCO has expressed grave concern over the destruction of cultural sites in Yemen -- where many sites had already been damaged since the 2011 overthrow of President Ali Abdullah Saleh -- and it announced an emergency response plan in May.

"In addition to causing terrible human suffering, these attacks are destroying Yemen’s unique cultural heritage, which is the repository of people’s identity, history and memory and an exceptional testimony to the achievements of the Islamic Civilization," director-general Irina Bokova said at the time.

The International Committee of the Blue Shield concurred in a statement released this week: "The world needs to take humanitarian action to help protect those who have been most harmed by this conflict and to help to protect the remains of their, and our, common past,"

The damage to cultural sites in Yemen may be motivated by different factors than those behind the Islamic State's own trail of destruction. The Saudi-led coalition may argue that strategic concerns or error have led to this damage, rather than the theological or financial logic that leads the Islamic State to lay waste to sites in Syria and Iraq.

Even so, the destruction of cultural sites is forbidden under a number of international treaties, including the 1954 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict. And besides, the end result is the same: the destruction of a history and a culture.

"In a struggle for power, the conflict won't distinguish between what's old and valuable and what's a military target," Mahmoud al-Salmi, a professor of history at Yemen's Aden University, told Reuters last month. "We risk losing these sites if the fighting goes on."

Yemen Post Newspaper

Yemen Post Newspaper

Fatik Al-Rodaini

Fatik Al-Rodaini