JUST off the coast of Port Said is an example of orderly behaviour that belies the often chaotic nature of life on land in Egypt. As the world’s container ships approach the northern opening of the Suez Canal, they form a majestic queue in the Mediterranean Sea, where they wait before gliding through the narrow passage.

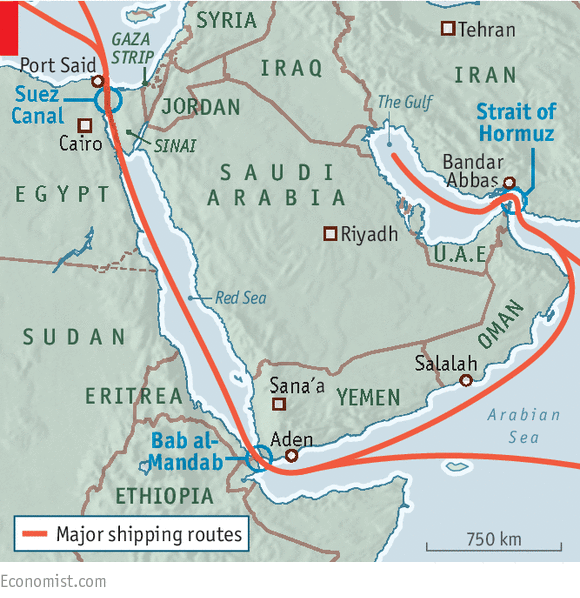

In recent years the shipping lanes of the Middle East, notably the Suez Canal, the Bab al-Mandab strait and the Strait of Hormuz (see map), have remained largely immune from the wars and rivalries of the countries that surround them. Even Iran’s mysterious seizure of a container ship off its coast on April 28th has done little to disrupt the flow. Shippers have grown accustomed to the volatility and believe the gatekeepers of crucial sea lanes have too much to lose by blocking them.

Not for the first time, Iran is testing that belief. One-fifth of the world’s oil trade slips by its coast along the Strait of Hormuz. Since it exports so much oil, impeding that traffic might seem self-defeating. But Iran has threatened to close the waterway before, most recently in 2012 in response to Western sanctions. And while officials in Tehran have linked the seizure of the container ship to a commercial dispute, many see it as mischief-making. The ship was released on May 7th, but the incident prompted America to deploy warships to watch over American-flagged vessels entering the strait, a practice since stopped.

Iranian ships have also shadow-boxed with American and Arab forces around the busy Bab al-Mandab, the strait leading into the Red Sea and the Suez Canal, through which around 10% of all sea trade passes. In mid-April an Iranian convoy looked set to run a blockade of Yemen enforced by a Saudi-led coalition that is bombing the country. Some think the ships were to supply the Houthi rebels, who are targets of the air-strikes. But the Iranians backed off when America sent an aircraft-carrier to the area. Iran has since positioned two of its destroyers at the entrance to the Bab al-Mandab, ostensibly to fight piracy.

Analysts have puzzled over Iran’s intentions, but the industry has remained unperturbed. Maersk, the Danish shipping giant that chartered the vessel seized by Iran, says the action was unjustified, but calls it an “isolated incident”. It has not changed its routes or security guidance for ships in the Middle East. Nor has the volatility hurt other firms. “We are seeing pretty much undisrupted shipping activity,” says Peter Sand of BIMCO, the world’s largest international-shipping association.

Dealing with uncertainty has become a normal part of business for shippers transiting the Middle East. Crews are often paid a premium. Maritime-security services assessing the routes reckon that fighting on land is unlikely to spill into the sea. The calm is reflected in insurance rates, which have not risen in response to recent events.

Even so, some countries are trying to enable ships to avoid Iran. Rattled by its threats in 2012, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates opened new oil pipelines that bypass the Strait of Hormuz. The six states of the Gulf Co-operation Council plan to build a railway from Kuwait to Salalah in southern Oman, where goods could be loaded onto ships in the Arabian Sea. But the pipelines can carry only a portion of the Gulf’s oil, and the railway, due to open in 2017, is expected to face delays.

Iran may anyway not represent the biggest threat to seaborne trade in the region. Non-state actors, which have no stake in the waterways, are more likely to disrupt them. Though once-menacing Somali pirates have been stopped by Western navies, there may be a new threat emerging from Islamist militants in Egypt’s Sinai peninsula, home to a disaffected Bedouin population just east of the Suez Canal.

Egypt’s security forces have struggled to deal with the militants, who stepped up their attacks after the coup against Muhammad Morsi, the former president, in 2013. An army crackdown merely alienated civilians and radicalised the fighters. The strongest group has pledged allegiance to Islamic State jihadists. It has killed hundreds of soldiers and police and also hit economic targets. The canal, which brings in some $5 billion a year, or about 2% of Egypt’s GDP, is one. On two occasions in 2013, one in broad daylight, jihadists filmed themselves firing RPGs at ships passing through the canal.

Such attacks are unlikely to sink container ships, but the militants may have drawn on old tribal and smuggling webs to gain heavier weapons, most likely from Libya. America, which sends dozens of naval vessels through the canal each year, is duly worried. Were a ship to be sunk, it might shut down the canal for weeks. Re-routing around the Cape of Good Hope would add some 4,300km (2,700 miles) to the journey from Saudi Arabia to America.

Still, shippers appear unruffled. Even amid the turmoil of the Arab spring and its aftermath, there was little disruption to the canal because each successive government viewed it as a national interest. Indeed, Mr Sisi hopes to add a new lane by the end of summer. “There is still a pretty rock-solid belief that the Egyptians will defend the canal,” says Mr Sand.