-

29 May 2015

- From the section World

Date: Fri, 29 May 2015 21:34:12 +0200

From the Mediterranean to the Andaman, it's been a season of despair, the faces of migrants haunting television screens and dominating headlines.

Harrowing stories have emerged of death, starvation and abuse at the hands of people smugglers. And from the world's new and continuing conflict zones, there have been new mass movements, across borders and within states.

Half a million Yemenis have been internally displaced since March. One hundred thousand Burundians have fled into neighbouring countries since April.

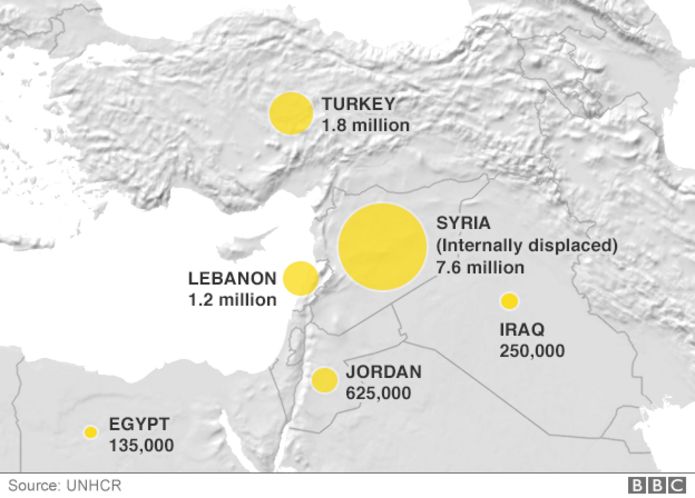

The statistics can be numbing - 7.6 million Syrians, homeless inside their own country, now make up a fifth of all internally displaced people (IDPs) in the world.

Are more people on the move than ever before?

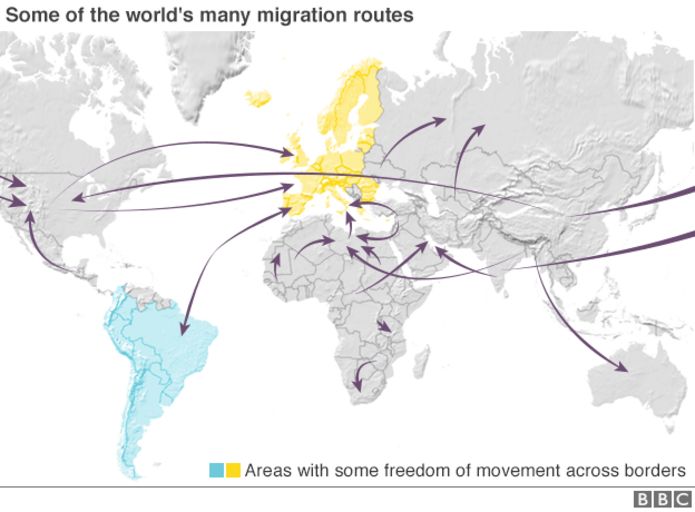

Today's map of the world is a complex spider's web of movement. Our map only represents the larger recent trends.

But it helps to explain why, in 2013, there were 232 million "international migrants" in the world (defined by the UN as people who have lived a year or longer outside their country of birth).

This figure includes refugees, asylum seekers and economic migrants - anyone who has crossed a border, legally or illegally, to escape disaster or persecution or simply to pursue a better life.

And it's almost certainly an under-estimate.

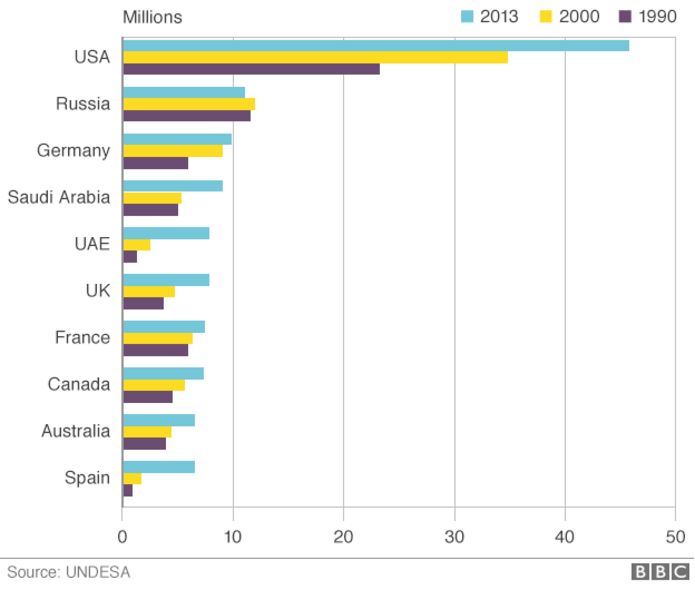

Where do international migrants live?

Half of all international migrants live in just 10 countries. The largest number (46 million) reside in the United States. By 2013, the US was host to 13 million people born in Mexico, but the fastest growth was among recent arrivals from China (2.2m) and India (2.1m).

Russia's second place is a result of Moscow's strong ties to former states of the Soviet Union, particularly Ukraine and Kazakhstan.

In Europe, Germany and France host some of the largest migrant populations (from Turkey and Algeria respectively), while vast numbers of migrant workers from southern Asia still live and work in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf.

In the UAE, international migrants make up a staggering 84% of the population.

Deadly crisis in the Mediterranean

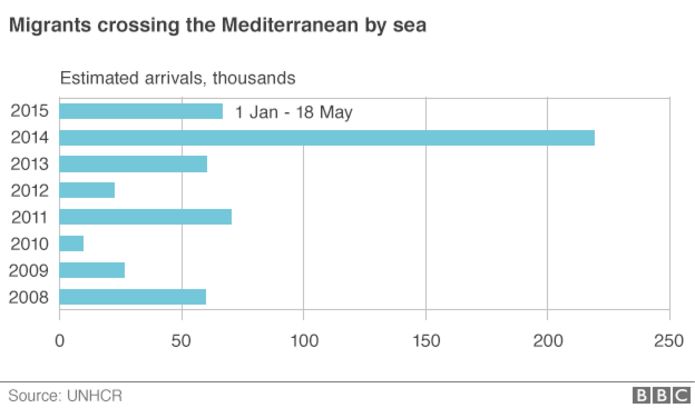

Dramatic scenes from the Mediterranean have captured headlines for the past two years.

Before the fall of the Libyan dictator, Muammar Gaddafi, numbers of migrants making the perilous crossing were actually declining.

Oil-rich Libya offered employment opportunities and Gaddafi was persuaded by the EU to limit onward movement.

But the year of his violent ouster, 2011, saw a sudden spike, and Libya's descent into chaos since 2012 has had a dramatic effect.

In 2014, more than 170,000 migrants arrived in Italy, the largest influx into one country in EU history.

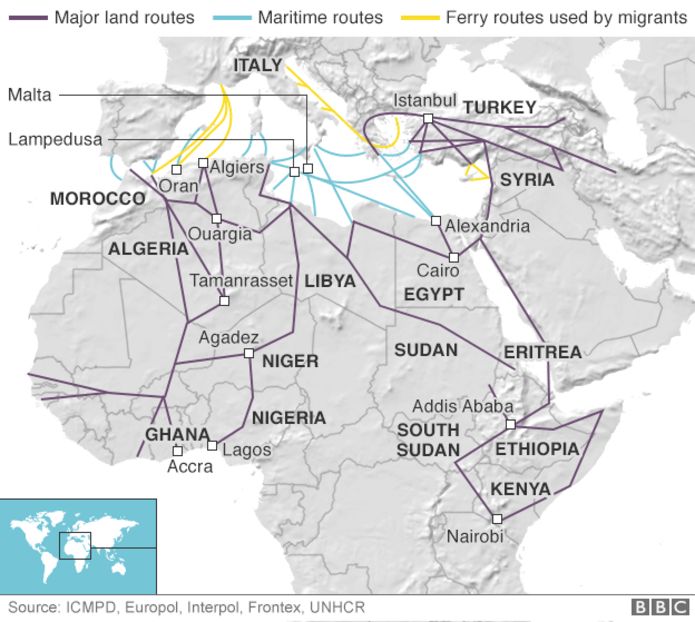

Perilous routes through Africa to Europe

The spider's web is at its most complex here. Some of these journeys are epic, with sub-Saharan and West African migrants crossing two perilous seas, one of sand and one of water, before arriving in Europe.

These journeys can take weeks or years to complete, with young men from Gambia, Senegal and Nigeria passing through several countries and relying heavily on people smugglers.

Among the largest groups crossing from Libya this year: thousands of Eritreans fleeing long-term conscription, as well as large numbers of Somalis and Nigerians.

In the eastern Mediterranean, huge numbers of Syrians cross from Turkey to Greece, accompanied by Afghans and Iraqis.

Syria: A displaced nation

Syria's civil war has now uprooted half the country's pre-war population. More than four million Syrians are refugees in neighbouring countries, with a much larger number internally displaced.

Syria is the main country of origin of asylum seekers in the industrialised world. This huge, growing exodus is one big reason why the number of forcibly displaced people in the world is now higher than it's been at any time since World War Two.

It also helps to explain why, when it comes to housing refugees, the burden falls more and more heavily on developing countries (86%, up from 70% a decade ago).

In the hands of people smugglers

Graphic scenes of the suffering experienced by refugees afloat in the Andaman Sea have drawn international attention to another desperate story of people smuggling and human deprivation.

The numbers are smaller than the Mediterranean, but the issues are similar.

Friday's meeting in Bangkok will attempt to grapple with this latest migrant crisis, but hopes are not high for any kind of action plan.

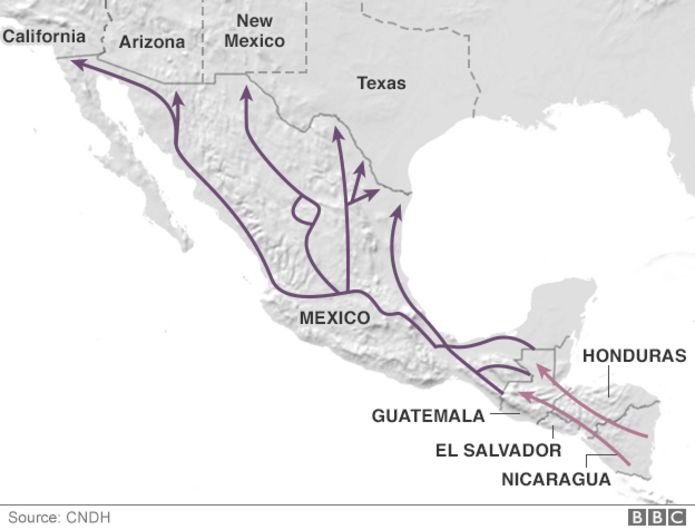

Journeys north through Mexico

The Mexico-Texas border remains the world's largest migration corridor. Mexicans are still the largest single group apprehended by US border officials but last year, for the first time, they were outnumbered by the combined total of other Central Americans.

Mexican migration has dropped, thanks to Mexico's improved economic circumstances, but worsening security situations have prompted large numbers of Hondurans, Salvadoreans and Guatemalans to journey north along a series of well-travelled routes.

The recent arrivals have included tens of thousands of unaccompanied children.

Growing global population

The share of international migrants in the world population has remained constant in recent years, hovering around 3%.

But as the world's population expands rapidly, so too does the raw number of people living outside their place of birth.

There are even more internal migrants: the figure of 740m is almost certainly a conservative estimate. It's hard to keep track of the millions of Chinese peasants who continue to converge on urban centres every year.

And the numbers of internal migrants fluctuate wildly: it's thought half a million Iraqis were displaced in a matter of weeks in June 2014.

Then there are natural disasters, which displace an average of more than 27m people every year.

Global migration fuels political debate, tests alliances and resources and keeps legions of statisticians very busy.