Thousands have arrived in Syracuse, New York, without family, friends, or more than a handful of English words.

SYRACUSE—Drive around this economically depressed city and the signs of the more than 10,000 refugees who have settled here are everywhere, from the ethnic grocery stores on the Northside to clusters of Somali Bantu women sitting in brightly colored veils and dresses in Central Village, one of the city’s housing projects in the Southside.

The number of refugees arriving in America is nearing a recent high, and will continue to track upward following an announcement by President Obama last month that the country would welcome at least 10,000 displaced Syrians.

Syracuse, like other cities in the North and Midwest that have experienced population losses, has put out the welcome mat for refugees, with Mayor Stephanie Miner joining 17 mayors in a letter to President Obama encouraging the country to accept even more Syrian refugees.

But Syracuse, like many other cities with large populations of refugees, is grappling with the challenges of bringing strangers from abroad to a down-and-out area. More than 70 different languages are spoken in Syracuse City schools, which a court has declared underfunded. Nearby Utica banned 17-to-20-year-olds from city schools, instead choosing to bus them to a school where they can’t earn a diploma. Syracuse is still trying to figure out how to find housing for refugees who can’t afford much and how to ensure, in a region where jobs are hard to come by, that refugees don’t fall into perpetual poverty.

So far, the city has struggled to deliver on those goals. According to analysis by Paul Jargowsky, a fellow at the Century Foundation, the number of high-poverty census tracts doubled in Syracuse from 2000 to 2013. Many of the areas that saw the highest jumps in concentrated poverty were Northside neighborhoods where large populations of refugees have resettled. Even there, refugees have a hard time finding affordable housing.

Refugee Admissions to the United States, 1995 to 2014

After trying to make a go of it in Syracuse, some refugees have decided to move on. The choice to pick up and move might be more feasible for the immigrants in Syracuse than it it is for those in other areas. The city has a larger proportion of “free cases” than other regions. Free cases are essentially refugees who do not come to join family members or sponsors, but who instead arrive knowing no one, said Felicia Castricone, who directs the refugee-resettlement program at Catholic Charities of Onondaga County. About 60 percent of Catholic Charities’ cases are free cases.

Castricone showed me around the Office for New Americans, a shabby brick building where refugees come for English lessons, rides to medical appointments, and meeting with case officers. In the basement classroom, women in headscarves sat at computers and upstairs, kids climbed on an indoor jungle gym while two Bhutanese children sat on a leather couch playing games on handheld devices.

People who come alone often find the challenges of securing a job and a permanent (and affordable) place to live especially difficult because they don’t have the same connections others may have. Osman Ali, a Somali refugee, is one of them. On the day I visited, he sat at a table at the Office for New Americans as a volunteer pointed to objects on an overhead projector, naming them one by one, in an effort to teach him English.

Ali is soft-spoken and clean-shaven, with a slight scar by his right eye. He lived in a refugee camp in Turkey until coming to Syracuse, and his mother and sisters are still in Somalia, waiting for him to send money home. When Ali arrived in Syracuse alone he was assigned to an apartment where he still lives by himself. He quickly found a job in Syracuse at a café owned by a Somali, but it closed because business was slow. “I am very nervous because I don’t have job,” he said. He’s been looking for two years now.

A volunteer teaches English at Catholic Charities in Syracuse (Alana Semuels)

A volunteer teaches English at Catholic Charities in Syracuse (Alana Semuels)

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services doesn’t have any hard data on the number of refugees who—like Ali—come by themselves, but of the 69,909 refugees who arrived in in the U.S. in 2013, about 24,000 were under 18 years of age, and about 27,000 were married.

Some refugees live with roommates, at least to start, or meet others when they’re learning English or receiving services with their refugee resettlement agency. But those that don’t can face the same affordable-housing challenges as other low-income people do.

“Refugees have very limited public assistance when they arrive and if they do not have a family to live with, are left with few housing options,” according to a report on housing in Syracuse county. “Very low-income households also struggle to find quality housing, a problem that was identified as being especially problematic for single refugees.”

Having children or a spouse significantly boosts the amount of money a person can receive, so solo refugees often get a much smaller amount of cash assistance. An amount that often doesn’t even cover the cost of an apartment, even in a relatively affordable city such as Syracuse, Castricone said.

“For a single person, they really need to get to work as soon as possible,” she told me.

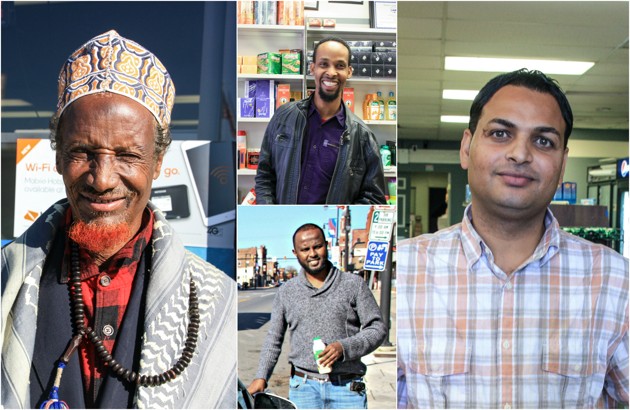

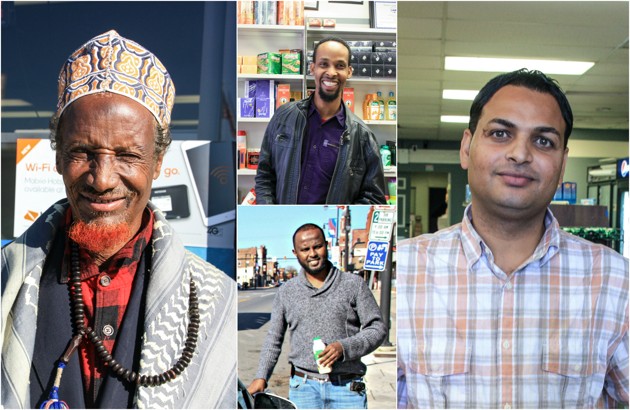

Somali refugees in Syracuse, clockwise from top middle: Warfalibaax Mursal, Osman Ali, Abdullah Ismael. The man on the left did not give his name. (Alana Semuels)

Somali refugees in Syracuse, clockwise from top middle: Warfalibaax Mursal, Osman Ali, Abdullah Ismael. The man on the left did not give his name. (Alana Semuels)

There are organic resources that people such as Ali find when they arrive. A day or two after he came, he was pointed to Mursal’s Store, a convenience store run by Somalis that also serves as an informal gathering place. The store is constantly bustling with Somalis coming in, wishing store owner Warfalibaax Mursal “as-salamu alaykum,” asking for help to send money to family or buying foods that they can cook to remind themselves of home.

Abdullah Ismael, a Somali taxi driver who came to the U.S. by himself a decade ago, pointed out a man he said arrived from the refugee camps only four days ago. The man had already found his way to Mursal’s store, he explained. Many refugees are more comfortable at Mursal’s store,—where they can speak Somali or Arabic—than they are in resettlement agencies, where they are encouraged to speak English. “This is our Armory Square,” he explained, referring to the bustling section of Syracuse’s downtown.

But while some parts of this informal social network created for people arriving in Syracuse alone are successful, the jobs piece is still a big challenge. Many refugees find work in hospitality or food services, or at the furniture manufacturer, Stickley, which employs a large number of refugees. Catholic Charities has launched a five-week daily training course that teaches refugees food-service skills.

Many of the jobs are in far-flung suburbs that are difficult to get to without a car, Mursal says. So people such as Osman Ali move on if they can’t find jobs.

Mursal, for example, was resettled in Syracuse with 11 family members. Eight have since moved to Minnesota, which has a large Somali population and where, he says, they felt more comfortable and had better connections for finding work.

Minnesota tops the country in secondary migration, with 2,206 people moving there from another state last year, according to the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement. Ohio was second, with 533, and Iowa and Florida had around 445 each. Arizona, California, and New York saw the most refugees leave to go to other states; in New York, in 2012, 156 refugees moved to the state from other places, but 566 left. That’s despite relatively generous benefit levels: Families can receive $770 from TANF and single adults can receive $475 a month in New York State. In Florida, they only get $303 and $180, respectively.

Refugees at a class at Catholic Charities in Syracuse (Alana Semuels)

Refugees at a class at Catholic Charities in Syracuse (Alana Semuels)

Refugees appear to move because they can’t find work in the states where they’re placed. In 2012, only 33 percent of refugees in Arizona were able to find work, and only 25 percent of those in California were employed, while 55 percent of refugees in Minnesota had entered employment in 2012.

Mursal has seen many Somalis arrive in Syracuse and leave, frustrated, after they’re unable to find work. Others only come for a few days and leave for elsewhere, since they’ve heard the opportunities are better there.

“Syracuse must create more jobs. They come here and then they go to Minnesota where someone can hook them up,” he told me.

Osman Ali has friends in Syracuse, and now knows the bus system and that he can survive through a cold winter. But he’s preparing to leave, perhaps to Ohio. It’s not a prospect he welcomes. In Syracuse, he has his apartment, his English classes, his buddies at Mursal’s store. But he doesn’t have a job, and his sisters and mother need him to work. So he’s striking out soon, moving again, in search of a new place to call home.