Date: Wed, 23 Sep 2015 22:06:15 +0200

US sanctions have not worked and the factors that led to the embargo have changed. A rapprochement would be in both US and Sudanese interests.

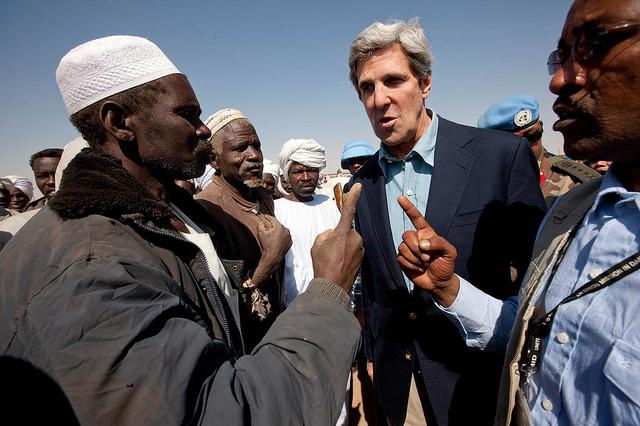

US Secretary of State John Kerry visits northern Darfur, Sudan. Photograph by Albert Gonzalez Farran/UNAMID.

The sun may have started to set on his tenure in office, but US President Barack Obama seems to have no intention of slipping into cruise control with regards to foreign policy. Against difficult odds, he recently mended fences with Cuba and Iran, two of the country’s longest-standing foes.

It may be tough for him to repeat the trick with North Korea given the Asian country’s apparent unwillingness to abandon its nuclear arsenal. But there is another international adversary with which the US could seek a relationship reboot: Sudan.

A regime led by President Omar al-Bashir is instinctively odious to many, but a lengthy US economic blockade has – like in Cuba – failed to achieve its laudable, if lofty, stated goal of hastening a peaceful, democratic state in Sudan. Meanwhile the key factors that led successive US administrations to dial up sanctions from 1993 to 2006 have changed fundamentally too.

South Sudan seceded peacefully in 2011. And while Darfur is still a hot mess, with more displacement in 2014 than any year since conflict erupted in 2003, it is largely due to tribal fighting rather than the iconic government-rebel war that brought the region to international infamy in the 2000s.

Amid newer global emergencies, it is donor fatigue – rather than obstructionism by Sudanese authorities – that has posed the main danger to international humanitarian relief in Darfur and elsewhere in the country: the UN has secured just 38% of its funding appeal for Sudan in 2015.

Troublingly, many civilians continue to die in government aerial bombing raids on rebel areas of the Nuba Mountains. Yet it is the rebels that have rejected an African Union-brokered ceasefire recently. Thrice. They have also attacked towns and killed scores of civilians indiscriminately, and the rebels refuse to get out of the way of a UN child polio vaccination effort.

Finally, the continued inclusion of Sudan on the US list of state sponsors of terrorism meanwhile is no longer warranted; Sudan remains a cooperative counter-terrorism partner of the US, as underlined in the most recent State Department yearly terrorism report.

Time to press the reset button

Just like Cuba and Iran, the unintended consequences of US sanctions on ordinary Sudanese have been devastating to living standards. Unlike these two other countries, however, the Sudanese government has zero leverage with America to engineer a mitigation of the embargo’s impact on vulnerable social groups. It lacks advocacy support from the diaspora in the US (as in the case of Cuba) or a potential nuclear capacity that would pose a strategic threat to the existence of US allies (as in the case with Iran).

Sudan, in short, does not really matter much in the hallowed corridors of Washington. If it did, policy towards the country would not have been captured, set, and held hostage by a coterie of US celebrity activists and their enabling anti-‘Khartoumites’ in successive administrations.

Consequently, Sudan has long found itself lumbered with an outsized economic embargo. That leaves it to President Obama to proactively free Sudan policy from the grip of dirigiste elements in his administration and celebrity activists and, in turn, put US sanctions onto a smart footing. He has compelling reasons for the US’ own strategic interests to do so.

The US cannot hope to shore up war-ravaged South Sudan without support from Sudan with whom it shares its longest border. Reconfiguring sanctions would encourage the Sudanese government to maintain its relatively benign stance to the war of its southern neighbour.

Similarly, the Sudanese government’s assistance to regional anti-ISIS, Houthi, and Boko Haram operations would all likely scale new heights if Obama eased US sanctions significantly. Relaxing the economic blockade would help Sudan better stem the flow of migrants from Africa to Europe too.

Circumstances in Sudan are not ideal – they likely never will be – to rejig the embargo. Freedom of the press remains irregular, rule of law and freedom of association both leave much to be desired, and government paranoia of civil society is rampant. But that is also true across Africa, including amongst US allies.

Most important, Sudan has no fundamental differences with the US and would quickly provide Obama with a strong and reliable partner amid unprecedented turbulence in the vicinity. The US blockade of Sudan cannot go on forever. It is a travesty of America’s notion of justice that the length of punishment should have no end in sight for ordinary Sudanese and a tenuous link at most to the original sin.

President Obama has acknowledged that the US had been mistaken to keep the same policy approach to Cuba and expect a different result. He has also recognised that it had not served the interests of the US, or of ordinary Cubans, to try to push Cuba towards collapse. It is time Obama realises the same holds for Sudan and acts on it.

Ahmed Badawi is Managing Director of the Sudan Centre for Strategic Communications (SCSC) in Khartoum, Sudan