As all eyes are turned to the vast Democratic Republic of Congo which is today facing a pivotal moment, neighbouring resource-rich Congo-Brazzaville's ongoing deadly political crisis seems forgotten.

Formerly named the French Congo after 1882, modern-day Congo-Brazzaville (or Republic of the Congo) was rocked by a significant outbreak of violence on 4 April 2016 on the day the Constitutional Court published final election results showing President Denis Sassou-Nguesso had won a hotly contested March presidential poll after he amended the constitution to remove presidential term limits.

"To normalise the situation, Sassou Nguesso started arresting the main opposition leaders, whom he deemed most dangerous, including Paulin Makaya, Gerenal Mokoko and his collaborators, but he realised this wouldn't be enough when he faced another form of resistance, this time para-military, organised by Pastor Ntumi in the Pool region," Andréa Ngombet, a young Congolese activist now living in Paris, exclusively told IBTimes UK. "So, he did what he knows how to do best: repression."

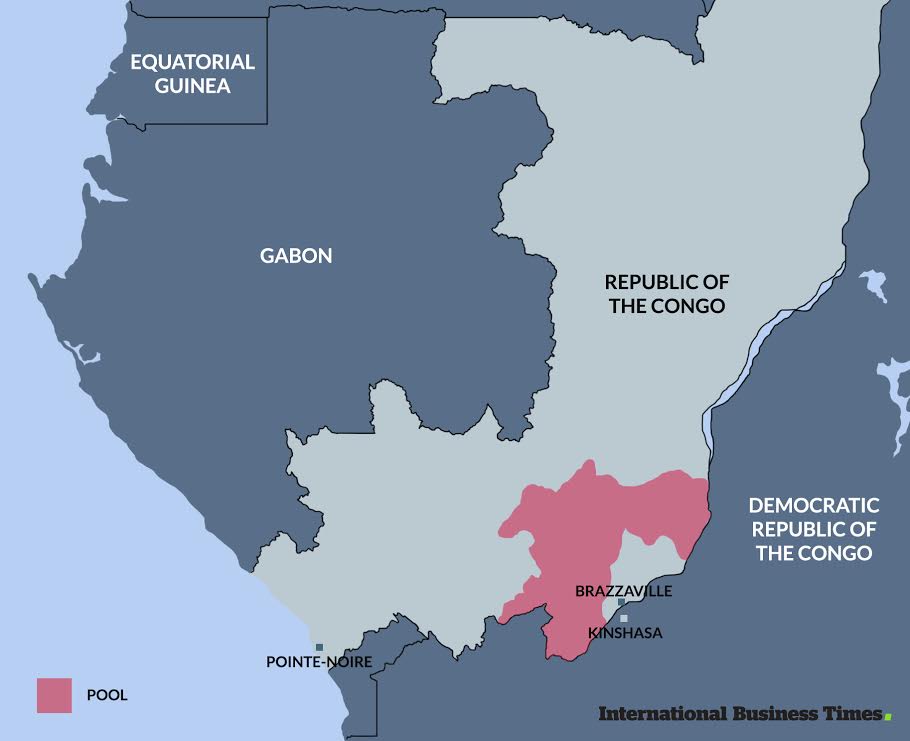

While the former French colony of four million rarely captures global attention, the Congolese opposition and several rights groups claim hundreds of civilians may have been killed and thousands more displaced in security operations carried out by Sassou Nguesso's government, including in Pool, the south-eastern region of Congo-Brazzaville.

The Pool, which the authorities describe as "terrorist command centres", is home to former rebel leader, Pastor Frederic Ntumi, whose suspected former rebels known as the 'Ninjas' are blamed for post-electoral fighting. The Ninjas signed agreements with the government to stop fighting in 2003, after wars and insurgencies dating back to the 1990s.

Now, the United Nation's Refugee Agency even talks of more than 13,000 displaced. With nowhere to go, they were forced into the forests. Now, with the rainy season they find themselves in an extremely precarious situation, with little water and food provisions running out.

The displaced told the UNHCR 50% of houses in some targeted villages were burned and they were scared to return. These war refugees now face famine and related conditions including acute malnutrition.

From August, the crisis took an international dimension, after an attack on the Congolese embassy in Paris, France, following which Sassou Nguesso allegedly looked for culprits.

André Okombi Salissa, another unsuccessful presidential candidate went into hiding, but members of his family and close associates have been arrested, including Augustin Kala Kala who was allegedly kidnapped on 29 September before he was found, almost tortured to death, in critical condition on 13 October on the doorstep of Brazzaville's morgue. Roland Gambou, Okombi Salissa's brother, died earlier this month following violent treatment in prison.

Makaya was sentenced to 24 months in prison and fined FCFA2.5m (£3,260, $4,005) in July this year for having organised and participated in a demonstration against the October constitutional referendum — a reform which allowed Sassou Nguesso to run again for presidency. Authorities accused Makaya, leader of Unis pour le Congo (UPC) party, of "incitement to public unrest" after the protest turned violent. Makaya appeared before a court of appeal to challenge his sentence less than 10 days ago, on 21 December. His bail application was denied. Makaya's appeal hearing will resume on 17 January 2017.

Accurate numbers are difficult to come about, but the Observatoire Congolais des Droits de l'Homme (OCDH), a local rights organisation, estimates there currently are some 100 political prisoners.

Last month, two rights organisations including OCDH received the testimony of Jugal Mayangui, a junior police staff officer, who was also severely tortured and left for dead some eight days later. According to his family, Mayangui was suspected of colluding with Pastor Ntumi. Trésor Chardon Nzila, OCDH's director, later reported military officials, who he alleged tortured Mayangui, told him: "You, Bakongo, we will exterminate you."

What do world leaders say?

"Despite these horrific crimes, the Congolese crisis is taking hold and is being forgotten for financial reasons, due to international corruption," Ngombet explained, highlighting several recent scandals.

These include the Rota do Atlantico (Route de l'Atlantique, or Atlantic road) case of alleged corruption between former Portuguese football manager José Veiga — nicknamed 'Monsieur Afrique ' — and Congolese officials.

Revealed in the Panama Papers expose, the so-called Chironi scandal established a link between Philippe Chironi, a French citizen living in Switzerland and Congo's ruling family. French courts suspect Chironi "of having participated in laundering operations of the misappropriation of public funds for the benefit of the Sassou-Nguesso family" — estimated at tens of thousands of euros, according to Le Monde. The Congolese president has denied any wrongdoing.

"Considering the sums revealed in the Panama Papers, we are talking about such wide international corruption that we understand that it is difficult, for many (political) actors to speak, because they may or may not be closely linked to some of these cases," Ngombet added.

With tensions running high, France, Congo's principal foreign ally, is struggling to take a defined stand because of a number of economic interests in the oil-rich region. Activists have urged President Francois Hollande to stop France's alleged support to Sassou-Nguesso.

Despite earlier reports of a meeting between US President-elect Donald Trump and the embattled Congolese leader, Trump's spokeswoman Hope Hicks on 27 December confirmed no meeting would take place. This decision, Ngombet said, may be attributed to activists' calls for the US not to associate itself with the Congolese head of state.

In addition to this, the country, on the verge of bankruptcy is facing floods and a deepening economic crisis, due to lower oil prices — the country's main source of revenue. "We are facing harsher days ahead, because the economic crisis is hurting us hard," Ngombet said. "We are just hoping that, as eyes turn to Kinshasa (DRC's capital) on the other side of the Congo river, they will sooner or later take a real interest in our situation".