In 1946, the right to health was first articulated in the World Health Organization (WHO) Constitution, stating that, “the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being.” Shortly thereafter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted by UN General Assembly Resolution 217A (III) of 10 December 1948, outlined that everyone has the right to health, including health care. Importantly, beyond its ethical and rights dimensions, health is fundamental to human happiness and overall well-being, while it also makes an important contribution to economic growth and progress, since healthier populations live longer, are more productive, and tend to save more.

A variety of factors influence health status and a country’s general ability to provide quality health services for its people. In addition to ministries of health, other government departments, donor organizations, civil society groups, and both communities and individuals themselves are important actors. For example, investments in roads help improve access to health services, inflation targets can constrain health spending, and civil service reform can aid in creating opportunities (or limits) to hiring more health workers.

Although a low-income, developing country and despite its being located in a challenging, politically unstable region, Eritrea has remained committed to expanding health and health care, and sought to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. Notably, the country has developed coherent, integrated approaches, emphasized equity and inclusion, and utilized cost-effective, pragmatic approaches, involving broad participation and multisectoral collaboration and action. In fact, according to a recent WHO report, upon a number of key health-related measures, Eritrea’s figures are distinguished as amongst the best, both within the region and comparatively across the continent.

In regard to malaria, Eritrea has categorized the infectious disease as an issue of utmost national concern. Significantly, approximately 70% of the population live in endemic, high-risk areas, with the Gash Barka region bearing greater than 60% of the burden. Of note, the most common malaria parasites found in the country are Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum. The former leads to severe disease and death, while the latter is the deadliest species of all malaria parasites infecting humans.

To control malaria, Eritrea has employed an assortment of strategies, including the promotion of national campaigns and community based-programs. Many programs have focused on providing extensive awareness and information, organizing focus groups, using preventative interventions, and encouraging the use of medical check-ups and medication. As well, control strategies have incorporated early treatment, indoor spraying, a focus on drainage and larviciding, mass distribution of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs), and a variety of source reduction efforts.

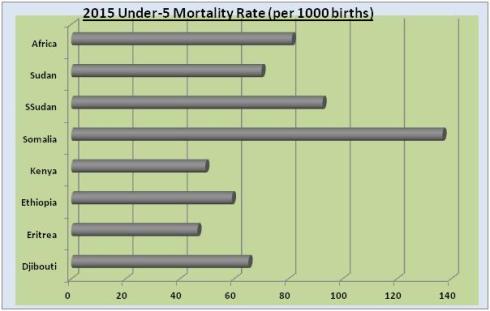

As a result of its multifaceted control measures, nearly 70% of children below age 5 now sleep under ITNs and over 60% of people own at least two ITNs. Consequently, national malaria incidence and deaths have declined dramatically, leading to Eritrea’s malaria intervention being described as “the biggest breakthrough in malaria mortality prevention in history.” According to the WHO, in 2013, Eritrea’s malaria incidence (per 1000 population at risk) was 17.4. By comparison, Djibouti’s incidence was 25, Ethiopia’s was 117.8, Kenya’s 266.3, Somalia’s 78.8, South Sudan’s 153.8, Sudan’s 37.7, Africa’s was 268.6, and the global average incidence was 98.6 (see Figure 1).

Another area of improvement for Eritrea has been in combating tuberculosis (TB), an airborne infectious disease which, alongside HIV/AIDS, is the most important cause of adult mortality in the world. According to the WHO, approximately 9 million people per year are infected with TB, with the large majority of these cases located within the world’s poorest, least developed countries. TB is caused by bacteria called Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The bacteria usually attack the lungs, but they can also damage other parts of the body. TB spreads through the air when a person with TB of the lungs or throat coughs, sneezes, or talks.

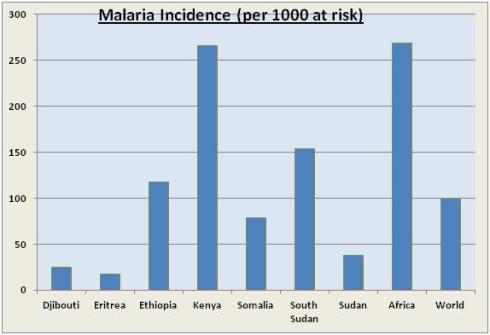

In Eritrea, TB has long been a significant public health issue – representing a major cause of morbidity and mortality – and an influential factor in severe economic loss and the exacerbation of poverty. However, since 1996, Eritrea’s Ministry of Health and the Tuberculosis Control Unit have focused on implementing a multisectoral approach that integrates holistic care, support, and treatment programs – all free of charge. Importantly, prevention has also been a priority, particularly in order to reduce overall health and medical costs. For example, TB sensitization and education programs have regularly been conducted in schools, public venues, and rural communities, while television programs, newspapers, posters, and brochures have raised general awareness. Consequently, Eritrea has made impressive progress in reducing the incidence of TB, with figures that stand out positively in comparison with its neighbours and global averages. Specifically, according to the WHO, Eritrea’s TB incidence (per 100,000 population) for 2014 was 78. By comparison, Djibouti’s incidence was 619, Ethiopia’s 207, Kenya’s 246, Somalia’s 274, South Sudan’s 146, Sudan’s 94, Africa’s 281, and the global average 133 (see Figure 2).

Finally, Eritrea has also made important progress in reducing both neonatal and under-5 mortality. Regarding the former, the first 28 days of life – the neonatal period – represent the most vulnerable time for a child’s survival. Notably, the proportion of child deaths which occur in the neonatal period has increased globally over the last 25 years. In terms of child mortality, the majority of deaths are preventable. Some of the deaths occur from illnesses like measles, malaria or tetanus, while others result indirectly from marginalization, conflict and HIV/AIDS. Globally, malnutrition and the lack of safe water and sanitation contribute to approximately half of deaths.

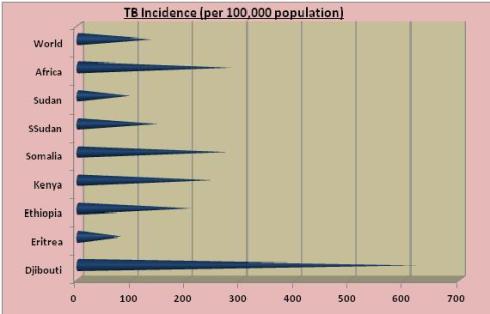

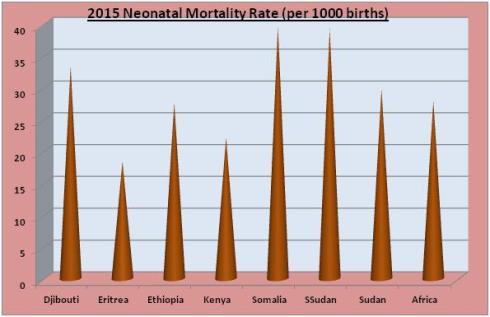

In Eritrea, reducing neonatal and under-5 deaths has involved practical, low-cost interventions delivered in an integrated, effective and continuous way. Measures utilized include, amongst others, expanding antenatal care, offering obstetric care, deliveries involving skilled birth attendants (e.g. who can resuscitate newborns at birth), ensuring good neonatal care (involving immediate attention to breathing and warmth, hygienic cord and skin care), early initiation of exclusive breastfeeding, providing insecticide-treated bed nets to prevent transmission of malaria, providing antiretrovirals for women with HIV, maintaining safe delivery and feeding practices, and the provision of vaccines, antibiotics, and micronutrient supplementation. Largely as a result of these measures, Eritrea has made tremendous strides in reducing neonatal and under-5 mortality. According to the WHO, in 2015, Eritrea’s neonatal and under-5 mortality rates (per 1000 births) were 18.4 and 46.5. In contrast, Djibouti’s measures were 33.4 and 65.3, respectively, while Ethiopia’s were 27.7 and 59.2, Kenya’s were 22.2 and 49.4, Somalia’s 39.7 and 136.8, South Sudan’s 39.3 and 92.6, Sudan’s were 29.8 and 70.1, and Africa’s were 28 and 81.3 (see Figures 3 and 4).

In its brief existence as an independent country, Eritrea has experienced significant progress within health and health care. This has involved the fulfillment and protection of fundamental rights and serves to provide an important platform for socio-economic growth and development. Moving forward, the country should remain committed to improving the health and development of its greatest asset – its citizens.

Figure 1: Malaria Incidence (per 1000 population at risk)

Figure 2: TB Incidence (per 100,000 population)

Figure 3: 2015 Neonatal Mortality Rate (per 1000 births)

Figure 4: 2015 Under-5 Mortality Rate (per 1000 births)