Date: Fri, 10 Feb 2017 14:59:30 +0100

Political unrest simmering in Ethiopia

Four months after declaring a state of emergency in a crackdown on protests, Ethiopia's government claims the country has returned to normal. Critics says the emergency decree remains an instrument of repression.

Author Merga Yonas

Date 10.02.2017

This coming April marks three years since protests broke out in Ethiopia. They were triggered by students in Ambo town, some 120 kilometers (74 miles) west of the capital Addis Ababa. The students were protesting against a controversial government plan dubbed "Addis Ababa and Oromia Special Zone Integrated Master Plan”.

The Ethiopian government maintained that the purpose of the plan was to amalgamate eight towns in Oromia Special Zone with Addis Ababa. The scheme would promote development.

However, residents in the eight towns were resentful of a plan they said had been devised behind closed doors. They were also worried that the plan, under the guise of development, would deprive farmers of their land, and have an unfavorable impact on local language and culture.

The protests which started in Ambo then spread to other towns in Oromia Regional State. On January 12, 2016, the Oromo People's Democratic Organization (OPDO), which is the local ally in the country's ruling coalition, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), revoked the plan.

But although the OPDO nominally represents regionally interests, the real power in the EPRDF is in the hands of the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF).

This sense of underrepresentation helped drive the protests in Oromia Regional State, which soon reached Amhara Regional State.

The response by the security forces to these protests, which had a strong following among young Ethiopians, was harsh. Hundreds were killed, thousands were injured, hundreds 'disappeared' and others went into exile.

But the protests conituned despite this lethal crackdown. In October 2016, the government responded by declaring a state of emergency for six months. .

Political crisis

Negeri Lencho, the minister who heads the government's communications office, told DW that the government had announced the state of emergency "not because it wanted to do it, rather it was forced to do it” because of the political crisis.

The administration of Prime Minister Hailemariam Dessalegn claims that the state of emergency has already brought peace back to the country. Critics could therefore agrue that it would be possible for the government to lift the decree even before the six months have expired. However, Lencho says that no timeframe has been declared so far either for the repeal or for the extension of the decree.

Opposition figures and members of the public DW spoke to dispute the claim that the state of emergency has restored peace to Ethiopia. The protests and the gunfire may have ceased, but the arbitrary arrests and human right violations continue.

Protests were initially triggered by anger over a development scheme for the capital Addis Ababa that demonstrators said would force farmers off their land

One Ambo resident, who asked to remain anonymous as he took part in the protests, said that the state of emergency had "unsettled the public's inner repose".

Repression was still in place, he said, despite the government "falsely" claiming that life was returning to normal.

"You cannot go out after curfew. You cannot stand anywhere with a few people. People are filled with fear. They fear the Command Post." The Command Post is the government body charged with implementing the state of emergency.

The town of Sabata, located 20 kilometers southwest of Addis Ababa, was part of the "Master Plan." One local resident said calm appears to have been restored to the town which was heavily affected by the protests, However the arrests and repression under the state of emergency continue, he said. "For example, there are youths who got arrested without a warrant and have been in prison for over three months on the charge that they have listened to music,” he told Deutsche Welle. "The state of emergency is being used by the state to take revenge against youth," he said.

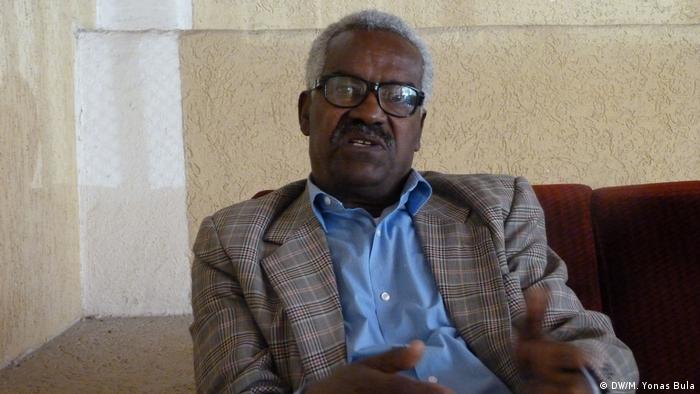

Mulatu Gamachu, deputy chairman of the oppostion Oromo Federalist Congress, says state security must avoid repression

Mulatu Gemechu, deputy chairperson of the oppostion Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC), said a de facto state of emergency had been in force in Oromia fo some time, but by making it public the government had acquired a legal shield for further acts of repression. Gemechu added that the country can become peaceful only when the state security forces with their firearms keep their distance from ordinary citizens and stop arresting people.

"If government claims peace is returning because of soldiers' presence, then it isn't peace,” Gemechu told DW.

Thousands of people were arrested following the declaration of the state of emergency. Although the Ethiopian parliament set up an inquiry board to investigate human right violations in the wake of the state of emergency, it has yet to submit its first report. Lencho says he has no knowledge of any such report.

Uncertainty over number of arrests

Government and opposition parties differ over the number of people who have been detained during the state of emergency. The government says 20,000 people have been arrested in Oromia, but Gemechu puts the figure closer to 70,000.

The government has said it will release more than 22,000 people. More than 11,000 were set free last Friday (03.02.2017)

The authorities said the prisoners were given "training in the constitution of the country and promised not to repeat their actions”.

But prisoners said that the government, in bringing together people from different areas to one location, had give them an opportunity to get to know each other and "strengthen their struggle and learn more about politics of the country”.