Date: Sun, 21 Feb 2016 18:25:27 +0100

The former secretary general of the United Nations and Egypt's Minister of Foreign Affairs for 14 years passed away on Wednesday

Boutros Boutros-Ghali, 93, died on Tuesday in a Cairo hospital after being admitted with a broken pelvis.

President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi issued a statement offering condolences to both the Ghali family and the nation following the death of the prominent legal and political figure.

The loss of Boutros Boutros-Ghali, who made admirable legal and political contributions to international life, will be felt in diplomatic quarters across the world, said the statement issued by the office of the president on Tuesday afternoon.

The statement said Ghali will always be remembered in Egypt for helping negotiate the Egyptian-Israeli peace initiative that allowed the full return of Sinai, and for his diligence in consolidating Egypt’s diplomatic relations across Africa.

El-Sisi called Ghali when he was admitted into hospital last weekend to wish him well.

Amr Moussa, former Arab League secretary-general, also offered condolences for the loss of “a true patriotic diplomat who spared no effort to serve the interests of his country and who managed to do so remarkably”.

Ghali’s international reputation derived on decades of academic and diplomatic work. He was born on 14 November 1922 to a leading Coptic family.

His grandfather, Boutros Ghali, assassinated in 1920, was the only Copt to serve as Egypt’s prime minister. In his three volumes of memoirs, based on the detailed journals he habitually kept, Boutros Boutros Ghali reflected on the political path his family had followed and often referred to his grandfather.

Typical of the sons of leading wealthy families, Ghali studied law at Cairo University and at the University of Paris.

He embarked on an academic career and, in cooperation with Mohamed Hassanein Heikal, the late legendary editor and chairman of Al-Ahram, helped establish Al-Ahram’s Alsiyassa Aldawliya (International Politics) magazine in 1965.

In his memoirs, Ghali wrote that he had always refused to fulfill his father’s hope that he join the diplomatic corps, only to be summoned by President Anwar Sadat in 1978 and offered a job as a minister of state for foreign affairs.

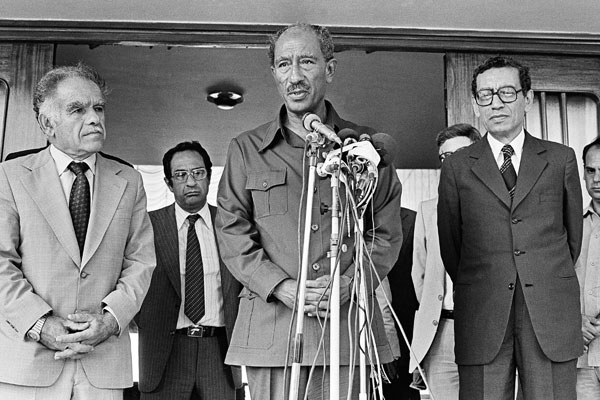

Ghali said that his instincts were to decline the post, but Sadat would not hear of it. As a consequence, Sadat was able to complete the Camp David negotiations that eventually led to the signing of the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty in March 1979, with Ghali at his side, despite facing the consecutive resignations of two foreign ministers.

Ghali always defended the choices Sadat made as the only possible path at the time. In private talks and in interviews, he consistently argued Egypt had no option but to move forward with the peace process so as to free up political and diplomatic energy to focus on relations with Africa, core to Egypt’s existence and for too long ignored.

In two volumes, Egypt’s Road to Jerusalem and Between Jerusalem and the Nile, Ghali offered detailed and revealing accounts of his efforts to encourage Sadat and his successor, Hosni Mubarak, to give greater priority to relations with Africa.

He conceded he was not always successful, his efforts hampered by Cairo’s focus on political developments in the Arab World and by African scepticism, with many of the continent’s statesmen accusing Egypt of chauvinism.

Fayza Aboul-Naga, national security advisor to the president and a former minister of state for foreign affairs, insists that despite the obstacles, “What Ghali did for Egypt in Africa is remarkable.”

Ghali was particularly successful in capitalising on Egypt’s support for liberation movements in Africa under President Gamal Abdel-Nasser in the 1950s and 1960s, says Aboul-Naga.

In 1980 Ghali set up a special unit for African cooperation within the Foreign Ministry. It was this unit, say Egyptian veterans of the Foreign Ministry’s Africa Desk, which managed, despite chronic underfunding, to keep bridges between Cairo and African capitals open, particularly through the medical, scientific and education missions it sent across the continent.

In 1991 Egypt nominated Ghali for the post of UN secretary-general. He became the first African to take the top job.

He wrote about his five years at the UN headquarters in New York in his memoirs, reflecting on the shifting topography of international relations that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union.

During his time at the UN he fell afoul of Madeleine Albright, then the US permanent representative to the UN, who told him his chances of securing a second term were close to zero. Washington, she said, would block his reappointment.

Arab and Western diplomats attributed Washington’s hostility to Ghali to the international inquiry he commissioned into the 1996 Israeli massacre in the Lebanese village of Qana, where civilians attempting to escape Israel’s Grapes of Wrath operation were shelled inside a UN compound. Ghali argued that US antagonism to him was more complicated, and was a direct result of his attempts to ensure that the UN could operate apart from the direct wishes of the US.

Aboul-Naga, who was a member of Ghali’s team during the UN years, argues that what matters is not the number of terms he served but what he tried to do while he was in the job.

Following his departure from the UN, Ghali served as secretary-general of La Francophonie from 1998 to 2002. He was later appointed honorary president of the National Human Rights Council by Hosni Mubarak, a position he resigned from following Mubarak’s ouster.

Ghali was married to Leia Maria Ghali. The couple had no children. His closest family member was his nephew, Youssef Boutros Ghali, who was a minister of finance under Mubarak and now lives in exile in London.

In recent years, Ghali said he had two wishes left that he would like to see fulfilled: to establish an organisation bringing together all the states of the Nile Basin, something he worked hard to achieve and that he hoped would have spared Egypt from its current stand-off with Ethiopia, and for an end to the dispute between his nephew and the state.

Youssef Boutros Ghali was tried, in absentia, following Mubarak’s 2011 removal, and after a five-minute hearing sentenced to 30 years.

Ghali, say younger and mid-career Egyptian diplomats, will always be remembered for having been someone who found it very easy to connect with the West but who never lost sight of, or faith in, Egypt’s relations with Third World countries, especially with Africa.

Ghali’s funeral service will be held Thursday at Al-Abbasiya Coptic Cathedral. A presidential source told Al-Ahram Weekly that the president is planning to join the Ghali family, friends and students in paying respects to the former UN secretary-general.