While the opposition tries to unite, the presidency seems to be working out various possible scenarios for staying in power.

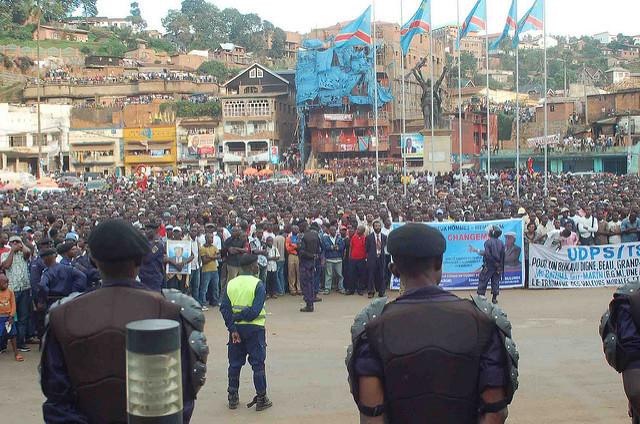

Crowds turn out to see veteran politican and opposition leader Étienne Tshisekedi in 2011. Credit: VoteTshisekedi.

For nearly a decade, the Democratic Republic of Congo has been an electoral democracy, a fragile and dysfunctional one, but an electoral democracy nonetheless. However, in the eyes of many Congolese, this status risks being forfeited at the stroke of midnight on 20 December 2016.

According to the DRC’s constitution, the president is permitted two consecutive mandates of five years. But with just five months to go until the end of President Joseph Kabila’s second term, there are no signs of an election to appoint his successor.

The government has regularly reaffirmed its commitment to elections and attributed the open-ended postponement to technical and financial factors. But given that Kabila doesn’t appear to consider himself bound by the constitution and that he has been notoriously uncommunicative about his intentions, many fear that he intends to delay the election until he can find a way to stay on for a third term.

On two separate occasions recently, Kabila has assured the people that elections are coming, but he omitted to say when they would be or whether he will be taking part.

Does Kabila want a third term?

In recent months, Kabila’s potential route to extending his presidency has become more visible. This May, the constitutional court – responding to a request from 260 pro-Kabila parliamentarians – ruled that that the incumbent is allowed to remain in office until elections are held.

This decision horrified the opposition who argue that the Senate President should take over if elections haven’t been held. But for Kabila’s allies, the ruling gives a veneer of legality to a scenario in which Kabila stays on beyond 19 December.

At the same time, supporters of the president appear to be preparing the country for the possibility of a referendum to modify the constitution. This plan – which was frequentlyfloated in 2013 and 2014 – seemed to have been dropped in September 2014 after the president of the National Assembly failed to secure parliamentary approval for a referendum. But it appears to now be back on the table.

Since June, Henri Mova Sakanyi and Ramazani Shadari – the respective secretary-general and deputy secretary-general of Kabila’s PPRD party – have been telling supporters and reporters that a referendum is the desire of the Congolese people.

For instance, the gung-ho Shadari told a reporter this month that “there will be a third term for Kabila that the population is going to impose…either by referendum or another form”. Meanwhile, in an interview on 11 July, Sakanyi cast Kabila as the reluctant leader selflessly awaiting the instruction of his people. “He doesn’t want to change the Constitution and a referendum is not on the agenda”, he said, before adding that a referendum would be “constitutional” and that if the population calls for one “we will bow before their will”.

To the surprise of no one, billboards and banners have also begun to pop up throughout the country welcoming a referendum and unending Kabila hegemony.

[See: DR Congo’s electoral process is at an impasse. Here are 3 scenarios for what comes next]

Obstacles to an extension

While progress may have been relatively smooth thus far, recent history suggests that this plan will not be plain sailing. After all, in 2014, the president’s allies failed to secure the 60% super-majority in the National Assembly necessary to organise a referendum.

In that vote, some of the politicians that made up Kabila’s parliamentary majority must have gone against his wishes. And in September 2015, the president’s dominance in the National Assembly was further weakened when a platform of seven parties – known as the G7 – split from the government.

Meanwhile, Kabila’s supporters must also be aware that any attempt to bludgeon a referendum bill through the legislature could trigger the kind of unrest witnessed inJanuary 2015. Back then, protesters in towns across the DRC took to the streets against proposed changes to the electoral law that could’ve extended Kabila’s rule. In the repression that followed, dozens were killed.

The insistence by the likes of Sakanyi and Shadari that the Congolese population is clamouring for more Kabila is also highly dubious. Kabila is deeply unpopular in much of the country and, although there is no reliable polling, it is thought the majority of the population would prefer to see a new head of state before the year is out. This means that even if the president’s political footsoldiers can engineer a referendum, it is probable they would have to deploy a variety of underhand tactics to win it.

If the route to Kabila’s continued rule via a referendum is ruled out, another possibility is that the president could anoint a dauphin to run with his blessing. There are no immediately obvious nominees for this role, but the possibility certainly seems to be under consideration. For instance, Kabila’s chief diplomatic counsellor has said that while the president will remain in power beyond the end of his mandate, he will leave office at the next election.

Whether this is Kabila’s preferred strategy or simply a Plan B if he can’t secure a third term is anyone’s guess. The contrary messages currently originating from Kabila’s allies may be explained by the fact the president is yet to make up his mind on the best strategy and is working on several possible scenarios.

Can the opposition unite?

What are the opposition’s prospects of spoiling the president’s plans? At first sight, the travails of Moïse Katumbi – whose presidential bid has been swiftly and ruthlessly neutered – suggest it will struggle.

The former governor of Katanga Province and member of Kabila’s PPRD quit the ruling party in September 2015. He secured the endorsement of two opposition platforms and launched his presidential campaign in this May.

But within two weeks, the 51-year-old found himself subject to an arrest warrant on allegations he had recruited foreign mercenaries. And then, on 22 June, while in South Africa for medical treatment, Katumbi was sentenced in absentia to three years in prison for illegally selling a building. Both charges have been denounced as politically motivated.

[See: Moïse Katumbi and the Congo’s race for the presidency]

Historically, the Congolese opposition has been fragmented, riven by competing egos and diverging visions. But at least publicly, most leading figures have acknowledged the importance of confronting Kabila with a united front and behind a joint presidential candidate.

However, this is easier said than done. When Katumbi launched his campaign, he did so with the backing of the G7 and a smaller coalition known as the Alternance pour la République (AR). But other major opposition parties such the UNC and MLC have so far shown a clear lack of appetite for a Katumbi presidency.

Nevertheless, efforts to unite have been central to the opposition’s strategy. And the showpiece of this quest took place on 8-9 June when Étienne Tshisekedi, who finished as the runner-up in the 2011 elections, held a two-day conference on the banks of Lake Genval in Belgium to which the leaders of the DRC’s main opposition parties and coalitions were invited. This gathering yielded the Rassemblement, a new platform established to resist attempts to change to the constitution and ensure Kabila’s departure from power this year.

Beyond providing the opposition with a renewed sense of cohesion, the creation of theRassemblement was significant for restoring the 83-year-old Tshisekedi – who was chosen to serve as the platform’s president – to the heart of the Congolese opposition. Tshisekedi regards himself as the winner of the 2011 election and has effectively been boycotting national politics since the acceptance of his defeat by the Supreme Court and international community. Furthermore, as of September 2014, he has lived in Belgium on account of his health which has further curtailed his ability to communicate with followers.

In spite of this hiatus, however, Tshisekedi remains the best known figure in the Congolese opposition – with the possible exception of Katumbi – and has an unparalleled capacity to mobilise support in important parts of the country, most notably Kinshasa. His central position in the Rassemblement undoubtedly gives the new organisation greater authority.

However, while the Rassemblement successfully gathered Katumbi’s devotees – the G7 and the AR – under the same roof as Tshisekedi’s UDPS, it appears to have driven a wedge within the third major opposition coalition: La Dynamique de l’Opposition. At the Genval conference, La Dynamique’s smaller parties took part enthusiastically, but the heads of the coalition’s two largest parties – Vital Kamerhe of the UNC and Eve Bazaiba of the MLC – were conspicuous by their absence.

It appears Kamerhe and Bazaiba are wary of what they see as the burgeoning relationship between Tshisekedi and Katumbi. The latter did not attend the conference but is thought to have been closely involved and was represented by the G7 and AR as well as his elder brother Raphael Katebe Katoto, who is close to Tshisekedi.

Since the conference, more has been said about La Dynamique’s position, but things remain unclear. The MLC’s Bazaiba has said that La Dynamique is not a member of theRassemblement but will collaborate with it. Senior UNC figures seem unclear about the nature of their involvement, and to compound the confusion, two of the party’s highest ranking officials participated in the conference in a personal capacity in spite of their party’s position. Meanwhile, the smaller parties within La Dynamique – the most significant of which is Martin Fayulu’s ECiDé – are simply behaving like fully signed up members and seem to have migrated to Tshisekedi’s orbit.

What now?

Both Tshisekedi and Katumbi have declared their intentions to return to the DRC for a ‘Grand Meeting’ of the Rassemblement in Kinshasa and nationwide demonstrations on 31 July. And if both men were to set foot on Congolese soil, it would undoubtedly invigorate Kabila’s opponents. It should be noted, however, that Tshisekedi’s homecoming has been announced without materialising on previous occasions, while Katumbi will be aware that he risks arrest if he returns.

In private, members of the opposition say they are waiting for certain key dates before revealing their hand. These include: 19 September, when the electoral body should call the election; 27 November, the latest date on which the vote should happen according to the constitutional timetable; and 19 December, the final day of Kabila’s mandated term. It will become much easier to evaluate the opposition’s strength and unity after witnessing the kind of force it can mobilise as we approach and pass these milestones.

At the moment, it seems that the only option to avoid the opposition and government clashing amidst a deepening constitutional crisis is the national dialogue that Kabila abortively launched last November. According to the president, this would be an inclusive forum aimed at ensuring credible elections, and the UN and international community have repeatedly called for it to be held. But to date, all the main opposition parties have rejected it, dismissing it as a trap.

Recently, however, the Rassemblement has agreed to discuss the possibility of a dialogue and has met with the forum’s panel of facilitators, which contains members of the African Union, UN, EU and La Francophonie. The UNC also now appears less hostile to the idea of an internationally-mediated conference.

But ultimately, the possibility of talks will depend on whether the opposition is prepared to compromise on certain pre-conditions, such as the liberation of political prisoners and strict adherence to the constitution. In other words, will they make a presidential promise to stand down in December the price of their participation? If so, it’s a price Kabila won’t pay and the talks will not happen.

If this is the case, President Kabila will remain in power over an increasingly exasperated country. Most Congolese citizens have not seen any improvement to their quality of life during Kabila’s two terms, and his efforts to prolong his unpopular reign could ignite the most frustrated sections of the population.

Latent anger combined with the increasing militarisation of the regime makes for a combustible cocktail. And if this impasse continues, with the last vestiges of Kabila’s legitimacy finally withering away on 20 December, it becomes more likely that Kabila’s future – and that of the DRC – will not be settled at the ballot box or in a mediated forum, but on the streets.

William Clowes is a journalist based in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Follow him on Twitter at _at_WTBClowes.