At the beginning of February, twenty-two years ago, the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front’s (EPLF) liberated the port city of Massawa. The victory in Massawa opened the floodgates for the liberation of Asmara, the capital city and eventually, the rest of Eritrea.

The loss of Massawa was a big blow to the Derg military junta of Ethiopia. In desperation, the Derg bombed the old historic port city of Massawa causing tremendous destruction to human life and to the city. While it may only have been a matter of time before the rest of Eritrea would be liberated, the question on everyone’s mind was if the Derg would do to Asmara what it had done to Massawa? What would be the fate of Asmara: a city established by women who longed for peace and harmony?

Asmara is the capital city of Eritrea, with a population of over four hundred thousand. Asmara is a shorter version of Arba’te Asmara. In Tigrinya, arba’te means four and asmara means "they (women) who united.” Taken together, it means “women who united the four.” There is archeological evidence emerging which indicates that there was an urban setting in Asmara and the vicinity of Asmara from early first millennium BC. However, for this essay, I’m referring to Asmara’s humble beginnings, which started when the women of four villages - Geza Gurotom, Geza Shelele, Geza Serenser and Gaza Asmae' - tired of continuous warfare, united their villages and menfolk and brought peace. It was in the women’s honor that the name "Asmara" came about. Therefore, Asmara is a city built on our early womenfolk’s peace dividend. It has kept its dividend to date. Today Asmara is one the safest cities in the world.

Asmara has always been a cosmopolitan city comprising different ethnic groups, religions, and nationalities. Due to Eritrea’s geographical proximity to the beginning of Christianity and Islam, Eritrea adopted both religions without force. The co-existence of the major religions has been time tested and, therefore, it’s not surprising to see the Catholic cathedral, the Grand Mosque, the orthodox Tewahdo church, the evangelical church and the synagogue are within walking distance from each other. Asmarinos, as they are affectionately and popularly called, wake up every morning to the sound of the call of the muezzin and the church bells ringing throughout the city.

Until Eritreans gained total control of their own country, Eritrea went through various colonial rulers: Ottoman Turks, Egyptians, Italians, British and Ethiopians. Street and neighborhood names, stamps and license plates retain evidence of the respective colonial rulers’ legacies. Names of streets were changed when one colonial ruler replaced another (even though some of the neighborhood's names from the pre-independence period still exist). The most vivid symbolic example of changing names is the main street in downtown Asmara.

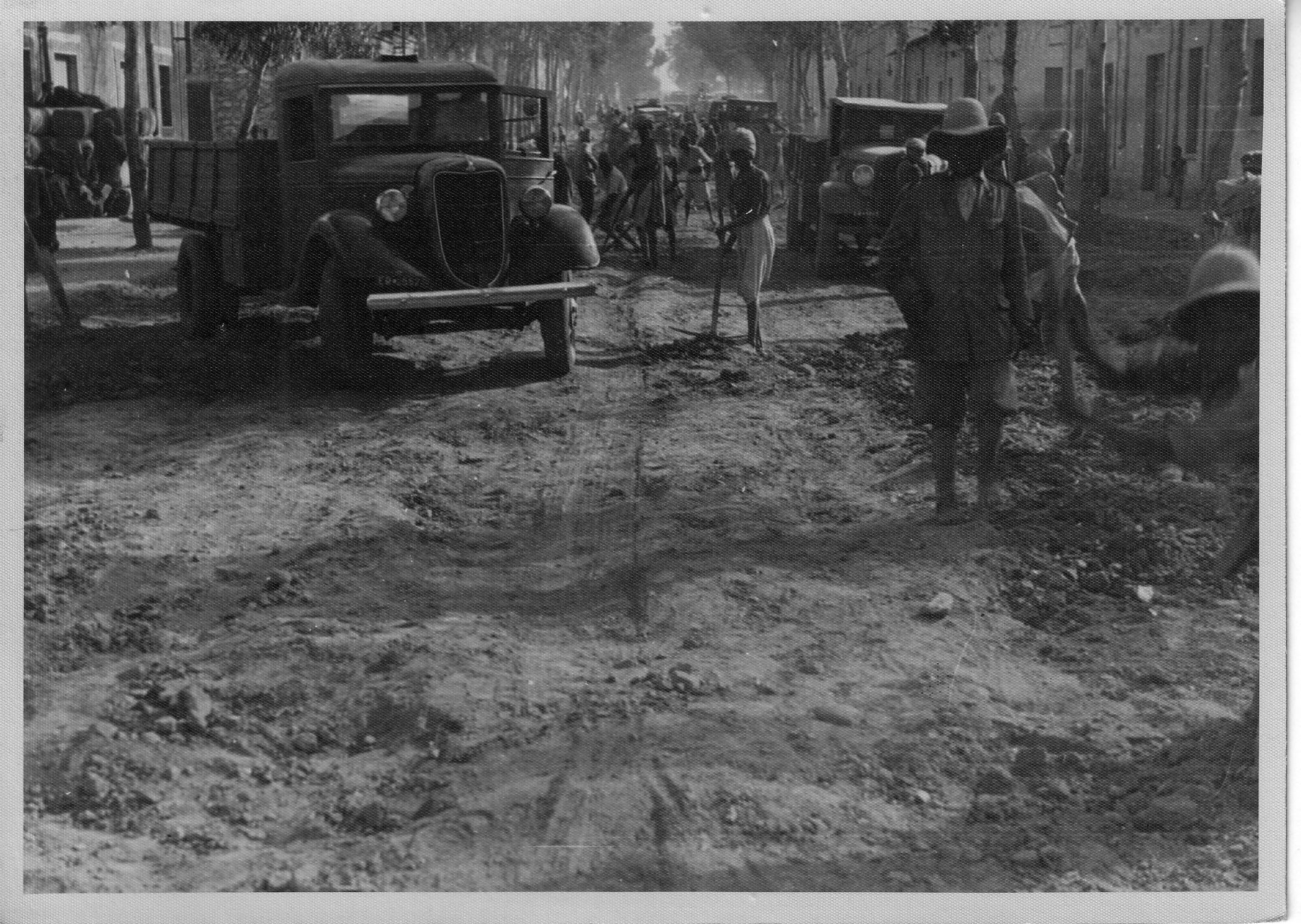

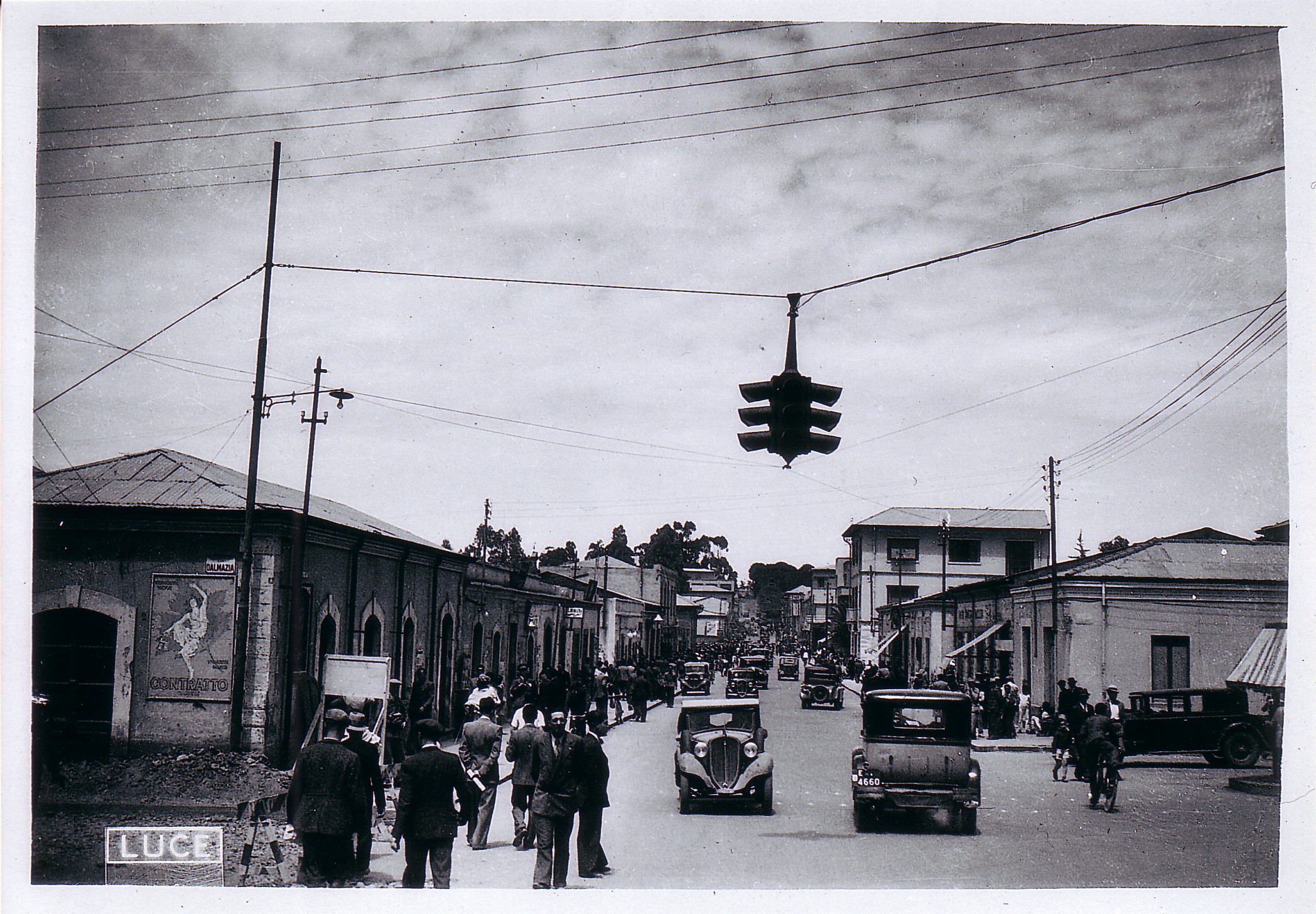

Mussolini Avenue: Italian period (1890-1941)

Queen Victoria Avenue: British period (1941-1952)

Godana Haile Selassie/ Emperor Haile Selassie Avenue (1962-1974)

Beherawi/National Avenue: The Derg period (1974-1991)

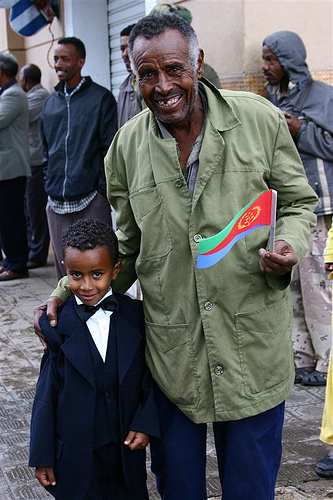

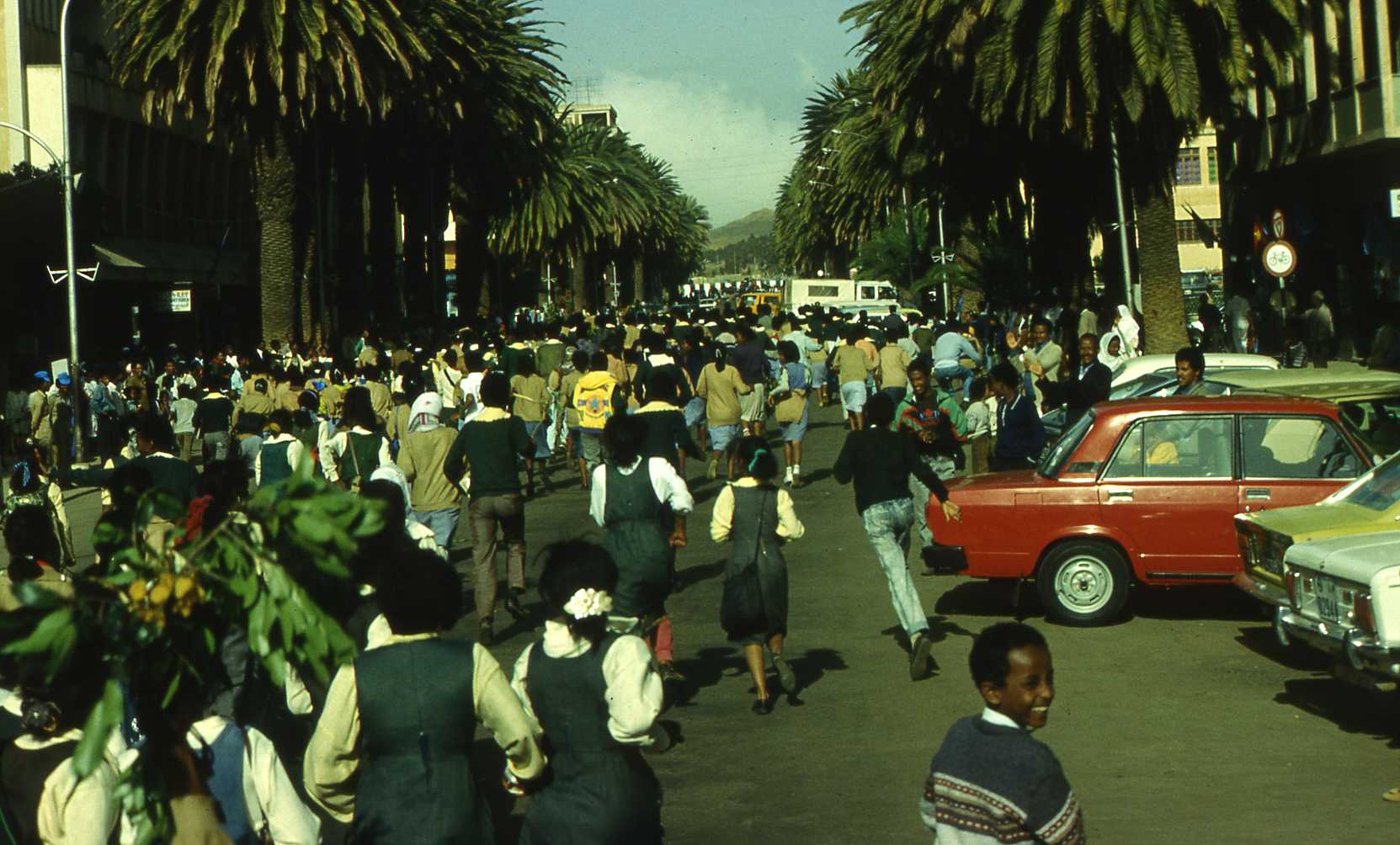

Godena Harenet/Independence Avenue (1991 until present)

These images present a pictorial odysseys of the city’s main street transformation through the various periods.

Asmara did not suffer the same destruction as Massawa. Only two years later, under the United Nations supervised referendum, Eritreans overwhelmingly voted (99.085%) for independence, thus making Eritrea “the oldest new nation”.

All images except 17 and 18 are courtesy of the RDC (Research and Documentation Center/ the defacto National Archives of Eritrea)

Images 17 and 18 are courtesy ©Eric Lafforgue.

Issayas Tesfamariam was born in Addis Abeba, Ethiopia to Eritrean parents. He moved to the United States in 1980. He studied film at San Jose State University and has a Masters degree from the University of San Francisco in Asia Pacific Studies. He has directed two films (Eritrea 2000: Under the Sycamore tree and more and Asmara: City of Radiance). He is working on four more documentaries on Eritrea. He has produced a coffee table picture book entitled, Eritrea: Colors in Motion. One of the pictures (firewood) in the book won San Jose State University's Global Studies department "Global Lens 2006" first prize. He was a lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley from 2005-2007. Currently he is the head of the Microfilming Department at the Hoover Institution Archives at Standford University. He is also a lecturer at the African and Middle Eastern Languages Department at Stanford University. He runs the blog, http://kemey.blogspot.com