“Regime change” or destabilizing sanctions are Official Washington’s policy options of choice in dealing with disfavored nations, but these aggressive strategies have proved harmful and counterproductive, says ex-CIA analyst Paul R. Pillar.

By Paul R. Pillar

Many variables are involved in the messy predicaments in the Middle East, but one way of framing the history and issues of U.S. policy toward the region is in terms of the approaches that have been taken toward so-called rogue regimes. That term, one should hasten to add, obscures more than it enlightens. But it has been in general use for a long time. Take it as shorthand to refer to regimes that have come to be considered especially troublesome and are subjected to some degree of ostracism and punishment.

Three basic approaches are available in formulating policy toward such a regime: (1) keep ostracizing and punishing it in perpetuity; (2) try to change the regime; or (3) negotiate and do business with it, to constrain it and to influence its actions. There are some contradictions between the approaches. Any regime that is led to believe that it is going to be overturned anyway, or that it will be perpetually punished anyway, lacks incentive to make concessions in a negotiation.

The approaches that outside powers, especially Western powers and above all the United States, have taken toward Middle Eastern regimes that have come to be considered rogue have varied — not only from one state to another but also over time in the policy toward any one state.

Iraq was subject to punishment for a long time, with the prevailing outlook not involving urgency to try different things. The perspective, as voiced by Secretary of State Colin Powell, was that Saddam Hussein was “in his box.”

Then suddenly the policy became one of forceful regime change, stimulated by nothing other than such a project has been on the neoconservative agenda and that the surge in militancy in the American public mood after the 9/11 terrorist attack, even though Iraq had nothing to do with that event, finally made realization of that agenda item politically possible.

Libya under Muammar Gaddafi was subject to years of punishment and ostracism. As far as international sanctions were concerned, this did have a specific declared objective: involving the turning over of named suspects in the bombing of Pan Am 103 in 1988. Once Qaddafi surrendered the suspects, real negotiation ensued. It resulted in an agreement that ended (while opening up to international inspection) Libya’s unconventional weapons programs and confirmed the Libyan regime’s exit from international terrorism.

Then, after an internal insurrection broke out in Libya, the idea took root — first in Western European capitals, although Washington would go along — that the situation should be exploited to intervene on behalf of the rebels and to help overthrow the regime. Regime change supplanted negotiation.

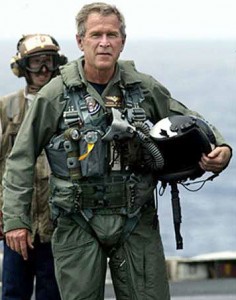

President George W. Bush in a flight suit on May 1, 2003, after landing on the USS Abraham Lincoln to give his “Mission Accomplished” speech about the Iraq War.

Policy toward Syria has been a mixed bag all along. There has been lots of punishment, but without some of the isolation to which other regimes have been subjected; the United States kept diplomatic relations with Syria even after placing it on the list of state sponsors of terrorism.

Once an internal revolt broke out in Syria, a situation similar to Libya arose, in that some outsiders (principally Gulf Arab states and Turkey) wanted to take advantage of the situation to topple the Assad regime. With Russian and Iranian help, and also for internal reasons, the regime has managed to hang on.

But “Assad must go” became a slogan elsewhere, and many in the West took regime change to be an objective. There was negotiation leading to the surrender and disposal of Syrian chemical weapons, but some, including in the United States, did not like that approach.

While there has been some backing away from the idea that Assad must go, others outside Syria say that still should be an objective. In short, there has been conflict and controversy, even within the United States let alone in any larger coalition, over just what the objective should be.

Iran has been subject to much punishment in the form of sanctions. Then after Hassan Rouhani’s election in 2013 there was real negotiation on an important issue. This led to the conclusion and implementation of a multilateral agreement that places limits on, and subjects to international scrutiny, Iran’s nuclear program.

A Balance Sheet

Before turning to a balance sheet regarding the results of these different approaches, some observations are in order about what has too often been overlooked with two of the approaches. The sustained use of punishment in the form of sanctions often has been accompanied by confusion about exactly what the objectives are — if that objective is to be anything besides punishment for punishment’s sake, which does not advance anyone’s interests.

An objective might be to make it directly harder for the targeted regime to do certain things, such as to procure advanced military technology. Or it might be to try to provoke an internal revolt, although this rarely works, for several reasons including where the blame for the pain usually falls.

Often the rationale for the sanctions is that it is an inducement to get the targeted regime to change its policies. But this does not work unless there is a positive alternative to the negative one of punishment and sanctions, and unless there is a firm expectation that the sanctions will end if the regime chooses a different, specific, identifiable course. And that is what has often been overlooked and missing.

This explains the years of failure of imposing sanctions on Iran without providing any positive alternative. If such an alternative had been offered, a nuclear agreement could have been reached years earlier, when Iran’s nuclear program was much smaller.

As for regime change, one needs to reflect first of all on just how irregular and extreme is the notion that if we don’t like someone else’s government, forcefully overthrowing it is to be considered as just another policy option. Such a notion is contrary to tenets of international law and international order than have been in effect since the Peace of Westphalia in the Seventeenth Century.

Also overlooked when regime change is turned to is how other people may have different ideas from our own about what rulers are legitimate and who should get their support — a factor in considering the status of Bashar al-Assad in Syria. Overlooked all too often as well is what comes after the ruler we don’t like is gone. A simple faith that something better is bound to fall into place has led to the problems we have seen in spades in Iraq and Libya.

Now for the balance sheet. The results of regime change in Iraq have been too glaringly bad to need a full recounting. They include a civil war that has never ended and has claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands, has disrupted the Iraqi economy, and has created enormous flows of refugees and displaced persons. These include the birth of a major terrorist group that we now know as ISIS. And for those who don’t like to see Iranian influence anywhere, the war that toppled Saddam resulted in the single biggest increase in Iranian influence in the region in at least the last couple of decades.

Libya has seen prolonged chaos since the removal of Gaddafi. Contending governments based in different parts of the country have competed for power, with only tentative and fragile progress made recently toward a reconciliation. The economy, despite the oil resources, is in shambles. Instability has been exported from Libya in the form of both men and materiel, and ISIS established in Libya its biggest presence outside of Iraq and Syria.

In Syria, the closest thing to successes have come from the bits of negotiation and diplomacy that have come into play: those involving the Assad regime’s surrender of chemical weapons and some partial and temporary cease-fires. The war in Syria — the war itself, not any particular political outcome in Damascus — has been a major breeder of extremism and the threat of instability spilling over borders.

Actions against the regime have brought counteractions not only from external supporters of the regime but also internal players who see the alternatives as worse for them. Moreover, it would be difficult to escape a similar conclusion from the point of view of our own interests — that is, that the most feasible alternatives to the current Syrian regime would not be those hoped-for moderate forces the building up of which always seems to fill short, but instead radical extremists.

The brightest spot in this regional picture is found in the one place where the policy move by the United States, in cooperation with international partners, has been in the direction of negotiation. That involves Iran, and the big result so far has been the agreement to restrict Iran’s nuclear program, which certainly is one of the most significant steps in recent years on behalf of nuclear nonproliferation.

It is just one issue, but an important one. And lest we forget, it was the issue about which anti-Iran activists had for so long been crying most loudly. What comes later in dealings with the Iranian regime will depend in large part on the continued attempts of hardliners in more than one capital, but especially in Washington, to sabotage the nuclear agreement.

But at least there has been an unshackling of diplomacy in the Middle East in the sense of establishing, even in the absence of full diplomatic relations, something closer than before to a businesslike dialogue with one of the most significant states about issues of mutual concern (including countering ISIS, an issue on which U.S. and Iranian interests run parallel).

It should have been apparent, on an a priori basis alone, that overthrowing foreign government we don’t happen to like is not to be considered as just another foreign policy option, even for a superpower. And it should have been apparent that punishment for the sake of punishment doesn’t do anyone any good, beyond registering our dislikes.

When we take into account the actual record of results from the different approaches that have been taken toward regimes we choose to call rogue, these conclusions should be all the more obvious.

Paul R. Pillar, in his 28 years at the Central Intelligence Agency, rose to be one of the agency’s top analysts. He is author most recently of Why America Misunderstands the World. (This article first appeared as a blog post at The National Interest’s Web site. Reprinted with author’s permission.)