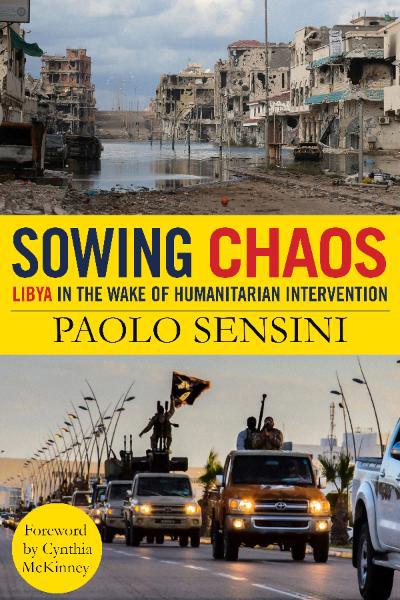

Libya’s post 2011 King Idris Flag

It is rare for a historian to write a history of a significant issue and bring it into the present time; even rarer when the work coincides with the reemergence of that issue on the world stage. Paolo Sensini has done just that with Sowing Chaos: Libya in the Wake of Humanitarian Intervention (Clarity Press, 2016). It is a revelatory historical analysis of the exploitation and invasion of Libya by colonial and imperialistic powers for more than a century.

It is also timely since the western powers, led by the United States, have once again invaded Libya (2011), overthrown its government, and are in the process (2016) of creating further chaos and destruction by bombing the country for the benefit of western elites under the pretext of humanitarian concern.

As with the history of many countries off the radar of western consciousness, Libyan history is a tragic tale of what happens when a country dares assert its right to independence – it is destroyed by violent attack, financial subterfuge, or both.

As with the history of many countries off the radar of western consciousness, Libyan history is a tragic tale of what happens when a country dares assert its right to independence – it is destroyed by violent attack, financial subterfuge, or both.

Although an Italian and Italy has a long history of exploiting Libya, a close neighbor, Sensini stands with the victims of colonial and imperial savagery. Not an armchair historian, he traveled to Libya during the 2011 war to see for himself what was true. Despite his moral stand against western aggression, his historical accuracy is unerring and his sourcing impeccable. For 234 pages of text, he provides 481 endnotes, including such fine sources as Peter Dale Scott, Patrick Cockburn, Michel Chossudovsky, Pablo Escobar, and Robert Parry, to name but a few better known names.

His account begins with Italy’s 1911 war against Libya that “Francesco Saverio Nitti charmingly described …. as the taking of a ‘sandbox’.” The war was accompanied by a popular song, “Tripoli, bel suol d’amore” (Tripoli, beauteous land of love). Even in those days war and love were synonymous in the eyes of aggressors.

This war went on until 1932 when the Sanusis’s resistance was finally crushed by Mussolini. First Italy conquered the Ottoman Turks, who controlled western Libya (Tripolitania); then the Sanusis, a Sunni Islamic mystical militant brotherhood, who controlled eastern Libya (Cyrenaica). This Italian war of imperial aggression lasted 19 years, and, as Sensini writes, “was hardly noticed in Italy.”

I cannot help but think of the U.S. wars against Afghanistan and Iraq that are in their 15th and 13th years respectively, and counting; they are not making a ripple on the placid indifference of the American people.

Sensini presents this history clearly and succinctly. Most of the book is devoted to the period following the 1968 overthrow of King Idris by the Free Unionist Officers, led by the 27 year old captain Mu’ammar Gaddafi. This bloodless coup d’état by military officers, who had all risen from the poorer classes, was called “Operation Jerusalem” to honor the Palestinian liberation movement. The new government, The Revolutionary Command Council (RCC), had “three key themes …. ‘freedom, socialism, and unity,’ to which we can add the struggle against western influences within the Arab world, and, in particular, the struggle against Israel (whose very existence was, according to Gaddafi, a confirmation of colonialization and subjugation).”

Sensini explains the Libyan government under Gaddafi, including his world theory that was encapsulated in his “Green Book” and the birth of what was called “Jamahiriyya” (State of the Masses). Gaddafi called Libya the “Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriyya.”

Under Gaddafi there was dialogue between Christians and Muslims, including the establishment of diplomatic relations with the Holy See, and visits from Eastern Orthodox and Anglican religious leaders. Fundamentalist Islamic groups criticized Gaddafi as a heretic for these moves. Gaddafi described Islamists as “reactionaries in the name of Islam.” His animus toward Israel remained, however, due to the Palestinian issue. He promoted women’s rights, and in 1996 Libya “was the first country to issue an international arrest warrant with Osama bin Laden’s name on it.”

He had a lot of enemies: Israel, Islamists, al Qaeda, the western imperial countries, etc. But he had friends as well, especially among the developing countries.

A large portion of the book concerns the U.S./NATO 2011 attack on Libya and its aftermath. This attack was justified and sanctioned by UN Resolutions 1970 (2/26/11) and 1973 (3/17/11). These resolutions were prepared by the work of the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) that in 2000-2001 produced a justification for powerful nations to intervene in the internal affairs of any nation they chose. Termed the “Responsibility to Protect” (R2P), it justified the illegal and immoral “humanitarian” attack on Libya in 2011. The ICISS, based in NYC, was founded by, among others, the Carnegie Corporation, the Simons, Rockefeller, William and Flora Hewitt, and John D. and Catherine MacArthur foundations, elite moneyed institutions devoted to American interventions throughout the world.

When the US/NATO attacked Libya, they did so despite the illegality of the intervention (an Orwellian term) under the UN Resolutions that prohibit arming of ‘rebels’ who do not represent the legal government of a country. On March 30, 2011 the Washington Post, a staunch supporter of US aggression, reported an anonymous government source as saying that “President Obama has issued a secret funding that would authorize the CIA to carry out a clandestine effort to provide arms and other support to Libyan opposition groups.” None of the mainstream media, including the Washington Post, noted the hypocrisy of reporting illegal activities as if they were legal. The law had become irrelevant.

The Obama administration had become the opposite of the Kennedy administration. Whereas JFK, together with Dag Hammarskjold the assassinated U.N. Secretary General, had used the UN to defend the growing third world independence movements throughout the world, Obama has chosen to use the UN to justify his wars of aggression against them. Libya is a prime example.

Sensini shows in great detail which groups were armed, where they operated, and who they represented. The US/NATO forces armed and supported all sorts of Islamist terrorists, including the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG), led by Abu al-Laith al Libby, a close Afghan associate of Osama bin Laden, and al Qaeda’s third in command.

“These fanatical criminals (acclaimed as liberators by the mainstream media worldwide) were to form Libya’s emerging ruling class. These were people tasked to ensure a democratic future for Libya. However, the ‘rebel’ council of Benghazi did what it does best – ensuring chaos for the country as a whole, under a phantom government and a system of local fiefdoms (each with a warlord or tribal chief). This appears to be the desired outcome all along, and not just in Libya.”

Sensini is especially strong in his critical analysis of the behavior of the corporate mass media worldwide in propagandizing public opinion for war. Outright lies – “aligning its actions with Goebbels’ famous principle of perception management” and the Big Lie (thanks to Edward Bernays, the American father of Public Relations) – were told by Al Jazeera, Al Arabiya, and repeated by the western media, about Gaddafi allegedly slaughtering and raping thousands of Libyans. Sensini argues persuasively that Libya was a game-changer in this regard.

Here, the mass media played the part of a military vanguard. The cart, as it were, had been put before the horse. Rather than obediently repackaging and relaying the news that had been spoon fed to them by military commanders and Secretaries of State, the media were called upon actually to provide legitimation for armed actors. The media’s function was military. The material aggression on the ground and in the sky was paralleled and anticipated by virtual and symbolic aggression. Worldwide, we have witnessed the affirmation of a Soviet approach to information, enhanced to the nth degree. It effectively produces a ‘deafening silence’ – an information deficit. The trade unions, the parties of the left and the ‘love-thy-neighbor’ pacifists did not rise to this challenge and demonstrate against the rape of Libya.

The US/NATO attack on Libya, involving tens of thousands of bombing raids and cruise missile, killed thousands of innocent civilians. This was, as usual, explained away as unfortunate “collateral damage,” when it was admitted at all. The media did their part to downplay it. Sensini rightly claims that the U.S./NATO and the UN are basically uninterested in the question of the human toll. “The most widely cited press report on the effects of the NATO sorties and missile attacks on the civilian population is most surely that of The New York Times. In ‘Strikes on Libya by NATO, an Unspoken Civilian Toll’, conveniently published after NATO’s direct intervention had ceased. The article is truly a fine example of ‘embeddedness’:”

While the overwhelming preponderance of strikes seemed to hit their targets without killing noncombatants, many factors contributed to a run of fatal mistakes. These included a technically faulty bomb, poor or dated intelligence and the near absence of experience military personnel on the ground who could direct air strikes. The alliances apparent presumption that residences thought to harbor pro Gaddafi forces were not occupied by civilians repeatedly proved mistaken, the evidence suggests, posing a reminder to advocates of air power that no war is cost or error free.

The use of words like “seemed” and “apparent,” together with the oft used technical excuse and the ex post facto reminder are classic stratagems of the New York Times’ misuse of the English language for propaganda purposes.

Justifying the killing, President Obama “explained the entire campaign away with a lie. Gaddafi, he said, was planning a massacre of his own people.”

Hilary Clinton, who was then Secretary of State, was aware from the start, as an FOIA document reveals, that the rebel militias the U.S. was arming and backing were summarily executing anyone they captured: “The State Department and Obama were fully aware that the U.S.-backed ‘rebel’ forces had no such regard for the lives of the innocent.”

Clinton also knew that France’s involvement was because of the threat Gaddafi’s single African currency plan posed to French financial interests in Francophone Africa. Her joyous ejaculation about Gaddafi’s brutal death – “We came, we saw, he died” – sick in human terms, was no doubt also an expression of relief that the interests of western elites, her backers, had been served.

It is true that Gaddafi did represent a threat to western financial interests. As Sensini writes, “Gaddafi had successfully achieved Libya’s economic independence, and was on the point of concluding agreements with the African Union that might have contributed decisively to the economic independence of the entire continent of Africa.”

Thus, following the NATO attack, Obama confiscated $30 billion from Libya’s Central Bank. Sensini references Ellen Brown, the astute founder of the Public Banking Institute in the U.S., who explains how a state owned Central Bank, as in Libya, contributes to the public’s well-being. Brown in turn refers to the comment of Erica Encina, posted on Market Oracle, which explains how Libya’s 100% state owned Central Bank allowed it to sustain its own economic destiny. Encina concludes, “Hence, taking down the Central Bank of Libya (CBL) may not appear in the speeches of Obama, Cameron and Sarkozy [and Clinton] but this is certainly at the top of the globalist agenda for absorbing Libya into its hive of compliant nations.”

In five pages Sensini tells more truth about the infamous events in Benghazi that resulted in the deaths of US Ambassador Christopher Stevens and three American colleagues than the MSM has done in five years. After the overthrow of Gaddafi, in 2012 Stevens was sharing the American “Consulate” quarters with the CIA. Benghazi was the center of Sanusi jihadi fundamentalism, those who the US/NATO had armed to attack Gaddafi’s government. These terrorists were allied with the US. “Stevens’s task in Benghazi,” writes Sensini, “now was to oversee shipments of Gaddafi’s arms to Turkish ports. The arms were then transferred to jihadi forces engaged in terrorist actions against the government of Syria under Bashar al-Assad.” Contrary to the Western media, Sensini says that Stevens and the others were killed, not by the jihadi extremists supported by the US, but by Gaddafi loyalists who had tried to kill Stevens previously. These loyalists disappeared from the Libyan and international press afterwards. “The reports now focused on al-Qaida, Islamists, terrorists and protesters. No one was to mention either Gaddafi … or his ghosts.”

The stage for a long-term Western intervention against terrorists, who were armed by the US/NATO, was now set. The insoluble disorder of a vicious circle game meant to perpetuate chaos was set in motion. Sensini’s disgust manifests itself when he says, “Given its record of lavish distribution of arms to all and sundry in Syria, the USA’s warning that, in Libya, arms might reach ‘armed groups outside the government’s control’ is beneath contempt.”

Sowing Chaos: Libya in the Wake of Humanitarian Intervention is a superb book. If you wish to understand the ongoing Libyan tragedy, and learn where responsibility lies, read it. If the tale it tells doesn’t disgust you, I’d be surprised.

In closing, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that former Congresswoman Cynthia McKinney, a stalwart and courageous truth teller, has written a fine forward where she puts Libya and Sensini’s analysis into a larger global perspective. As usual, she pulls no punches.