Date: Sat, 13 Aug 2016 23:49:46 +0200

Islamist Extremism in East Africa

Summary

The growth of Salafist ideology in East Africa has challenged long established norms of tolerance and interfaith cooperation in the region. This is an outcome of a combination of external and internal factors. This includes a decades-long effort by religious foundations in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states to promulgate ultraconservative interpretations of Islam throughout East Africa’s mosques, madrassas, and Muslim youth and cultural centers. Rooted within a particular Arab cultural identity, this ideology has fostered more exclusive and polarizing religious relations in the region, which has contributed to an increase in violent attacks. These tensions have been amplified by socioeconomic differences and often heavy-handed government responses that are perceived to punish entire communities for the actions of a few. Redressing these challenges will require sustained strategies to rebuild tolerance and solidarity domestically as well as curb the external influence of extremist ideology and actors.

A market in Mombasa, Kenya.

Highlights

- While Islamist extremism in East Africa is often associated with al Shabaab and Somalia, it has been

expanding to varying degrees throughout the region. - Militant Islamist ideology has emerged only relatively recently in the region—imported from the Arab

world—challenging long-established norms of tolerance. - Confronting Islamist extremism with heavy-handed or extrajudicial police actions is likely to

backfire by inflaming real or perceived socioeconomic cleavages and exclusionist narratives used by

violent extremist groups.

The risk of Islamist extremism frequently focuses on Somalia and the violent actions of al Shabaab. Yet local adherents to extremist versions of Islam can now be found throughout East Africa. As a result, tensions both within Muslim communities and between certain Islamist groups and the broader society have been growing in recent years.

These tensions have not emerged suddenly or spontaneously. Rather, they reflect an accumulation of pressure over decades. The genesis of this is largely the externally driven diffusion of Salafist ideology from the Gulf states. Buoyed by the global oil boom and a desire to spread the ultraconservative Wahhabi version of Islam throughout the Muslim world, funding for mosques, madrassas, and Muslim youth and cultural centers began flowing into the region at greater levels in the 1980s and 1990s. Opportunities for East African youth to study in the Arab world steadily expanded. As these youth returned home, they brought with them more rigid and exclusivist interpretations of Islam. The expanding reach of Arab satellite television has reinforced and acculturated these interpretations to a wider audience.

Questioning the Nature of Apostasy in Islam

In 2014, Abdisaid Abdi Ismail published a book questioning whether the death penalty for apostasy was just in Islam. In doing so he joined a growing stream of Muslim scholars rejecting the use of Islamic tenets as a political tool to support violent movements. The response in the region was dramatic. He himself was labeled an apostate, received death threats, and was kicked out of hotels in Kenya and Uganda. Some East African clergy called for his book to be burned. Their protests ultimately led to the book being removed from Kenyan bookstands—despite more than 80 percent of Kenyans being Christian and just over 10 percent being Muslim. His experience reveals the extent to which moderate voices and open debate on the teachings of Islam are being suppressed—reinforcing more rigid interpretations of Islam in East Africa.

The effect has been the emergence of an increasingly confrontational strain of Islam in East Africa. Salafist teachings, once seen as fringe, became mainstream. The number of Salafist mosques has risen rapidly. In turn, it became increasingly unacceptable to have an open dialogue on the tenets of Islam (see box). Growing intolerance has fostered greater religious polarization.

Over time, these tensions have turned violent. Attacks by militant Islamists against civilians in East Africa (outside of Somalia) rose from just a few in 2010 to roughly 20 per year since then. The vast majority of these have been in Kenya. Most sensational was the days-long 2013 siege of the Westgate shopping complex in Nairobi, where militants caused more than 60 civilian deaths and left hundreds injured. Though al Shabaab claimed responsibility for the attack, experts agree that the attack required support from multiple local, Kenyan sympathizers. Al Shabaab committed an even deadlier attack the following year when Somali and Kenyan members of the group stormed the campus of Kenya’s Garissa University and killed 147 students. Al Shabaab has attempted to maximize the potential divisiveness of these attacks by singling out non-Muslims for execution.

Local, smaller scale attacks have also increased in regularity. Bus stations, bars, shops, churches, and even moderate mosques and imams have been targeted. Some of these attacks have been attributed to the Muslim Youth Center (MYC), a Nairobi-based group that has lauded Islamic militant activities. MYC, which began using the name al Hijra in 2012, has also supported al Shabaab with fundraising and recruitment and was allegedly linked to the Westgate attack. In Mombasa, violent street clashes between followers of militant Islamist clerics and the police have erupted on a number of occasions.

In Tanzania, Sheikh Ponda Issa Ponda and his group Jumuiya ya Taasisi za Kiislam (“Community of Muslim Organizations”) have been accused of inciting riots and burning churches in Dar es Salaam. Tanzania is also home to the al Shabaab–linked Ansaar Muslim Youth Center.1

The U.S. embassy in Uganda has regularly issued warnings of possible attacks since 2014. One of those alerts coincided with Ugandan forces foiling an imminent attack by a Kampala-based terror cell, arresting 19 people and seizing explosives and suicide vests.2 Most memorably, Uganda suffered twin bombings in July 2010 that killed 76 who had gathered at a restaurant and a rugby club in the capital to watch the World Cup final. Al Shabaab claimed responsibility but in 2016 seven men from Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya were convicted of carrying out the attack.

Aftermath of the 1998 U.S. embassy bombing in Kenya.

Connections between the region and the global jihad movement also appear to be expanding. While Kenya and Tanzania were targets of the al Qaeda–orchestrated U.S. embassy bombings in 1998 and the Mombasa tourist hotel attack in 2002, the region has not been a hotbed of support for global jihadism. However, Tanzanian Defense Minister Hussein Ali Mwinyi has warned that increasing numbers of citizens were joining the Islamic State and al Shabaab.3 At some point, these East African recruits may also return home, presenting a new security threat.

The rising violence of Islamist extremists has generated a strong response from security actors in East Africa. At times, these operations are conducted indiscriminately, however. The Kenyan government’s Operation Usalama Watch, for example, resulted in the incarceration of an estimated 4,000 people, the majority without charge. Largely conducted in regions with sizable Somali Muslim populations, the impression of many in these communities was that they were being unjustly punished for the acts of a handful of extremists.4 The result may be more support for violent Islamist groups. Interviews with Kenyan-born members of extremist Islamist groups found that 65 percent of respondents pointed to Kenya’s counterterrorism policy as the primary factor that motivated them to join their violent campaign.5

In short, Islamist extremist ideology has been spreading throughout East African communities—bringing with it greater societal polarization and violence. Further escalation is not inevitable, however. The region has a long tradition of inter-religious harmony. Nonetheless, experience demonstrates that radical Islamist ideology can be very difficult to counter once it takes root in a society. It is vital for East African governments and citizens, therefore, to understand both the external and domestic drivers of these extremist ideologies, so that the process of radicalization can be interrupted before it cements itself within local communities and grows increasingly violent.

The Evolution of Islam in East Africa

Muslims have lived in East Africa for generations. Trade and cultural exchanges between East Africa and the Arab world are centuries old. These links predate European colonization and retain substantial social and economic influence. Precise numbers are not fully known but Muslims seem to comprise between 10 and 15 percent of the population in Kenya and Uganda and some 35–40 percent of the Tanzanian population.

There has never been a uniform Islamic community in East Africa. Rituals, celebrations, and theological interpretations vary across the region. Most East African Muslims subscribe to Sunni interpretations of Islam, though there are also Shi’ia communities and members of the Ahmadiyya sect. Sufism, often described as a “mystical” interpretation of Islam that includes the veneration of saints, is also common. Some Muslim communities have absorbed practices and rituals from traditional African beliefs, including attributing spiritual significance to sacred objects. Despite these differences, religious communities in the region, whether Muslim or non-Muslim, have historically tended to coexist peacefully and overlook differences in theology or religious practice.

This has changed for some communities in recent decades as a result of the growing influence of Salafist ideology. A small but growing number of Muslims have adopted more exclusivist interpretations of their religion, thereby changing their relationship with other Muslims, with other faiths, and with the state. The radical view of a global struggle for Islam is by no means pervasive but it is very much present in a way it was not before.6

One channel by which this shift has occurred is through education. Lacking other opportunities for schooling, Muslim families in marginalized areas rely on madrassas, or Islamic schools. Over the last several decades, these madrassas have been the beneficiaries of growing streams of funding from centers of religious education based in Arab countries. In the process, these students have been steadily exposed to the cultural and religious identity of their sponsors.

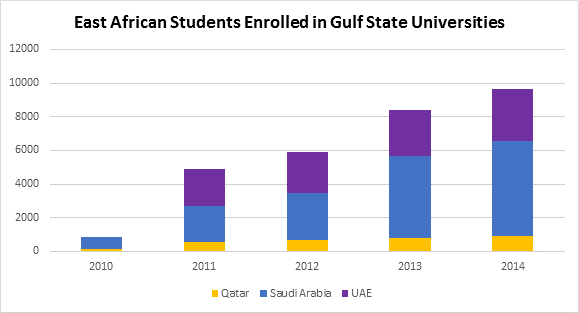

Opportunities for tertiary education have also expanded. While college degrees in the West continue to be viewed as most prestigious, following the 2001 World Trade Center attacks Western countries raised immigration hurdles. At the same time, scholarship opportunities in the Arab world were ramping up. This trend has continued and has been accelerating since 2010 (see figure). Out of practicality, many East African Muslims turned to these opportunities and became exposed to more fundamentalist versions of Islam.

Another vehicle through which interpretations of Islam in East Africa were shifted was through access to media from the Arab world. The expansion in the number and geographic reach of Arab satellite TV stations in the 1990s and 2000s brought Arab cultural norms to a wider audience in East Africa on a daily basis. This fostered more conservative interpretations of Islam regarding dress, the role of women, and differentiated relationships between Muslims and non-Muslims.

Sheikh Ponda Issa Ponda

The traction of such ideas is evident in the expanding popularity and influence of extremist clerics. Salafism, which had been a fringe off-shoot of Islam in East Africa in the 1990s, has become common today. A leading proponent in Kenya was the preacher Abou Rogo Mohammed, who for over a decade denigrated non-Muslims, criticized moderate Muslims, and instructed followers to forsake inter-religious dialogue, to abstain from politics, and to boycott elections. In one sermon Rogo deemed an attack on a church that killed 17 people as “just retribution” for Christian encroachment on Muslim lands. Rogo, who was closely affiliated with the militant Islamist group al Hijra and other conservative Islamic schools, separately proclaimed that “in this country we [Muslims] live amongst infidels.”7 Rogo’s ideology has persisted since his death in 2012. Tapes and DVDs of his and others’ incendiary sermons are still traded throughout the region.

In Tanzania, extremist clerics now aggressively challenge the authority of more moderate Islamic organizations and incite protests and clashes with government bodies under questionable pretenses. Sheikh Ponda has also challenged moderate Islamic groups such as Baraza Kuu la Waislam Tanzania (Bakwata), a quasi-state Islamic body. He and his followers have called for boycotts of state censuses and the removal of education officials whom they claim discriminate against Islamic schools.8 Ponda’s network, which has been active since the 1990s, includes hundreds of mosques and dozens of Islamic schools across Tanzania. Extremist interpretations of Islam and notions of a religious divide and persecution by the state have crept into the sermons of other Tanzanian Islamic preachers as well.9 As in Kenya, such rhetoric has come with an uptick in attacks, including against foreigners and Christian leaders.10

External Influences

A major contributing factor to East Africa’s shift toward more militant interpretations of Islam is the influence of well-funded foreign Islamist groups. This includes so-called Wahhabi organizations whose sponsorship of educational and religious activities has been fueled by the wealth of Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and other oil-rich Gulf states. Unlike East Africa’s historical tradition of infusing religious customs with local traditions, Wahhabism is an extremely conservative interpretation of the Koran. It forbids most aspects of modern education, requires strict dress codes, abides by ancient traditions of social relations, and disregards many basic human rights, particularly for women. While Wahhabism does not on principle denounce other faiths, many Wahhabi preachers do not tolerate other viewpoints. Even other interpretations of Islam, such as Sufism, are considered heretical and offensive to Wahhabis.11 In effect, the version of Islam that is being imported to East Africa is rooted within a particular Arab cultural identity.12 This is very different from the Islamic traditions that have evolved in other Muslim countries like Malaysia or Indonesia.

Kuwaiti officials at an Africa Muslims Agency building in Tanzania. Photo: Fadhili Abdallah.

Foreign-sponsored East African Muslim groups have had a presence in East Africa since the mid-20th century, but have expanded significantly since the 1970s.13 One estimate pegged funding from Saudi Arabia at $1 million per year on Islamic institutions in Zanzibar alone.14 The aims of the foreign funding are diffuse, going to social centers, madrassas, primary, secondary, and tertiary educational institutions, and to humanitarian and social programs. Many investments are large and multiyear. The Kuwait-based Africa Muslims Agency is a prime example.15 It has operations across the continent, including in Kenya, Malawi, Madagascar, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. One such operation involves a 33-year agreement signed in 1998 with the Zanzibari government to operate a university that has so far produced over 1,200 graduates.16

Not all beneficiaries of these funds are strictly Wahhabi or conservative to begin with. Some schools, social centers, and humanitarian outreach programs mix Wahhabi materials and programs with secular activities to reach a broader audience. In Kenya, the Saudi government has for decades provided financial support and scholarships to the Kisauni College of Islamic Studies in Mombasa, where Abou Rogo Mohammed studied.17 Likely dozens and potentially hundreds of madrassas and primary and secondary schools in Kenya have been built and underwritten in a similar manner.

Some activities supported by these foreign Islamic groups are laudable. They have sponsored medical care and provided aid during disasters, similar to other faith-based and secular organizations. However, these humanitarian activities are not entirely benign, since many of these Islamic groups will integrate proselytization into all their activities or will require that participants abide by strict, conservative customs to access funds or benefits.18

Logo of the Al Haramain Islamic Foundation. Image: HCPUNXKID

Some groups do have links to militant Islamist organizations. The Saudi-funded Al Haramain Islamic Foundation, for example, which had a large presence in refugee camps and supported many madrassas in East Africa, including some linked to Ansaar Muslim Youth Center, was closed and expelled from Kenya and Tanzania for such links.19 The Revival of Islamic Heritage Society, a Kuwaiti nongovernmental organization, was likewise found to have been providing financial and material support to al Qaeda–linked organizations, including al Shabaab’s predecessor, Al-Itihaad al-Islamiya (AIAI). Notably, AIAI’s Somali leaders were largely educated in the Middle East.20

Whether universities or bare-bones madrassas, educational institutions have obvious strategic value in shaping the beliefs of youth. Some of these schools do provide valuable instruction in math, sciences, and more. However, they also inculcate a rigid interpretation of Islam that is exclusionary and emphasizes da’wa, or the further proselytization of this brand of Islam. The curriculum also sometimes follows a principle called “Islamization of knowledge” developed in an effort to reconcile fundamentalist Islamic ethics into the disciplines of law, banking, and finance, among others. Over time, students absorb very definitive ideas of what is and what is not Islamic and who is and who is not a Muslim—and are encouraged to actively advance these same views.21 This is a recipe for confrontation, even if the programs that initially promoted such views did not advocate violence.

“The version of Islam that is being imported to East Africa is rooted within a particular Arab cultural identity.”

This growing influence of extremist Islam in East Africa has mostly been limited to particular neighborhoods, cities, or regions. But those effects have been cumulative and compounding, leading an increasing number of groups in the region to adopt progressively more aggressive and confrontational missions. The growth of networks that may be sympathetic to violent extremism lays the groundwork for the local collaboration that has been seen or suspected in deadly al Shabaab attacks in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda.

Socioeconomic Grievances

While the extremist Islamist ideology taking hold in East Africa is imported from elsewhere, exacerbating factors play a role in how meaningfully such ideology resonates upon exposure. For instance, despite terrorists exhibiting varying levels of wealth, education, zealousness, and experience, socioeconomic marginalization fuels the credibility and dispersal of extremist narratives. In East Africa, perceptions of unequal socioeconomic status and some ill-advised state actions have nudged Muslims toward more conservative tendencies and enabled “us versus them” narratives to resonate.

East African Muslims do have legitimate grievances. Youth unemployment in Kenya’s Muslim-dominated Coast and North Eastern provinces are 40–50 percent higher than the national average.22 Rates of primary and secondary school completion and attendance tend to be lower in Muslim counties, probably because there are fewer schools and teachers per student in the two coastal provinces than in other parts of Kenya. Similar patterns can be seen in Tanzania. The youth unemployment rate in the overwhelmingly Muslim island of Zanzibar has been about 17 percent in recent years,23 almost twice the national average of 9 percent.24 Also, the primarily Muslim coastal areas often have poorly defined property rights, hindering economic opportunities and paving the way for occasional land seizures by the government or large, non-local businesses.

Public opinion surveys depict a less divisive portrait at national levels. One survey of Kenyans showed that about half of Muslim respondents perceived their living conditions as the same or better than others. In comparison, about two-thirds of Christian respondents felt the same way. Still, this reflects Muslim sentiment that roughly matches the rest of Kenyan society—a perspective that has persisted for a number of years according to earlier survey rounds in 2008 and 2011.25 In Tanzania, 53 percent of Muslims surveyed perceived their living conditions as the same or better than other Tanzanians. Christians answered identically. Such results likely reflect the long history of harmonious interfaith relations in the region and the continuing resilience of such bonds when viewed at a nationwide level.

A mosque in Mombasa. Photo: Terri O’Sullivan.

The challenge of Islamic extremism is often a more local phenomenon. Perceptions of religious discrimination are higher in particular areas where divisive and exclusionary Islamic narratives have been present and circulating longer, such as Mombasa, Zanzibar, Tanga, and sections of Dar es Salaam and Nairobi. Accordingly, East African Muslims who subscribe to extremist interpretations of Islam remain a small (though vocal) minority. Yet the growth of this minority reflects and perpetuates a steady erosion of East African resilience in the face of the extremist Islamist ideology that has been coursing the region.

Claims that Muslims are deliberately denied economic, educational, and other opportunities relative to their non-Muslim compatriots have become common within the region’s Muslim communities, moderate and extremist alike.26 For many Muslims, particularly youth, such inequality validates the divisive messages of fundamentalist Islamic centers, madrassas, and mosques.

Government Actions That Alienate

East African governments have pursued legal action against various Muslim leaders in recent years in an attempt to isolate suspected extremists. Unfortunately, many of these judicial efforts have failed, further reinforcing a sense that the government is unfairly persecuting Muslims. For instance, when Sheikh Ponda was tried for inciting riots in Tanzania in October 2012, poorly framed charges and a weak investigation led only to a short, suspended sentence. Ponda was later charged again with inciting Muslims in Zanzibar and Morogoro to strike and riot. Yet, after 2 years of litigation he was acquitted for lack of evidence. Even then, prosecutors announced their intent to raise the twice-lost case to Tanzania’s High Court. In Kenya, Sheikh Mohammed Dor was charged with incitement after allegations that he intended to fund a coastal separatist group. Prosecutors soon altered the charges, a judge then postponed the trial, and eventually the state dropped its case entirely.

“This growing influence of extremist Islam in East Africa has mostly been limited to particular neighborhoods … but those effects have beencumulative and compounding.”

Prominent Muslim leaders in Kenya and Tanzania have also been detained by security agents without charge. Some have been mysteriously assassinated. Allegations of police-sponsored death squads that target radical Muslim leaders have been circulating widely for years. One incident attributed to such a squad is the death of Abou Mohammed Rogo, who was killed in a drive-by shooting in Mombasa in August 2012. In his vehicle were his father and daughter as well as his wife, who was injured. A little over a year later and just weeks after the Westgate mall attack in Nairobi, Rogo’s successor Sheikh Ibrahim Ismail and three others were killed in another drive-by shooting. Ismail’s successor, Sheikh Abubakar Shariff, known as Makaburi, was killed in April 2014, just 2 days after the police’s anti-terror unit linked him to al Hijra attacks in Mombasa the previous month.

Muslims for Human Rights, a Kenyan advocacy group, has claimed that police and prosecutors may be turning to extrajudicial measures due to their inability to conduct proper investigations or prosecutions of suspected Islamic extremists. That narrative has only strengthened over time. Human Rights Watch reported that, from 2014 to 2016, Kenyan security forces “forcibly disappeared” at least 34 people during counterterrorism operations in Nairobi and the northeast, and in at least 11 cases dead bodies were found of people who had recently been arrested by government authorities. One of Kenya’s top investigative journalists has claimed that the numbers were even higher, saying that he has uncovered 1,500 extrajudicial killings of citizens by the police since 2009.27

Sheikh Farid Hadi Ahmed

Similar charges have unfolded in Tanzania. In October 2012, Sheikh Farid Hadi Ahmed, the head of the Uamsho Islamic group, which advocates for an autonomous Zanzibar under Islamic law, went missing. Uamsho leaders called for the police to investigate. Supporters launched demonstrations, some deadly. Ahmed reappeared after 4 days and claimed that he had been abducted by police officers. He was promptly arrested by police and held without bail for months under a provision of the National Security Act. A judge ultimately dismissed several district-level charges against Ahmed since prosecutors failed to furnish any evidence against him. However, charges of incitement and conspiratorial involvement in his own kidnapping remained in place. Prosecutors then blocked Ahmed’s ability to file for bail or even to enter a plea. After taking his case to Tanzania’s High Court, Ahmed was eventually granted bail in 2014 after 17 months in jail. Six months later, he was rearrested on terrorism charges.

Beyond the specifics of this or other cases, the lack of transparency and pattern of haphazard arrests, bail policies, and prosecutions have made many Muslims suspicious of political leaders and state institutions. Combined with a sense that they have been economically marginalized, many are increasingly disinclined to work through existing governance structures in order to right perceived wrongs. As a result, extremist and exclusivist Islamic narratives can seem more compelling.

Reversing the Spread of Extremism

This review has shown that the drivers of Islamist extremism in East Africa are both external and internal. A framework for redressing this threat, therefore, will require a series of actions on both levels.

Counter external influences and emphasize domestic traditions of tolerance

Destabilizing, exclusivist Islamist narratives—a relatively recent import—have begun to erode a long history of tolerance in East Africa. Governments and civil society groups need to counter these by capitalizing on and strengthening the region’s much longer history of religious diversity and tolerance. This will take genuine and patient engagement on behalf of political leaders as well as indirect efforts to support more inter-religious dialogue that yields constructive and tangible benefits for participants.

As part of reinforcing indigenous, tolerant traditions, governments will have to address funding by foreign, fundamentalist Islamic entities. This will require adopting transparent and consistent means to regulate the funding sources, sectarian rhetoric, and militant leanings of religious groups. Groups that promote violence or open confrontation should clearly be banned and prosecuted. In addition, funding for social services should be separated from proselytization. However, blanket criminalization of conservative Islamic groups should be avoided as this will likely spur more support for violent movements. Rather, a policy of tolerance with a clear prohibition against violence and divisiveness should be pursued.

Improve political inclusion of Muslim communities

Political leaders should acknowledge that Muslims have some legitimate claims of marginalization, whether by design or neglect. This alone will send a powerful message to Muslim constituencies and may spark a sense of trust in collaboration and reform. Leaders should also expand engagement with Muslim communities, including those that may have experienced some radicalization but have not advocated violence.

Mohamud Ali Saleh

When security improved in Kenya’s northeast in the latter half of 2015 it was credited to the regional coordinator Mohamud Ali Saleh, a former ambassador to Saudi Arabia who had been named to the post after the Garissa University attack. The subsequent reduction in terrorism observed in this region stemmed not from more robust enforcement but rather as a result of Saleh’s skills as an interlocutor between the government and local communities. This resulted in improved community policing and intelligence tip-offs.

Invest in citizens economically and institutionally

Socioeconomic inequalities must be transparently addressed so they are minimized as legitimate grievances. Programs should target inequality of education, income, and opportunity, regardless of whether the root cause is truly religious discrimination or in fact a symptom of regional, urban, or rural dynamics. Programs could aim to boost employment levels in Muslim-majority areas.

Strengthening and clarifying property codes and land rights would also help. Muslims in coastal East Africa who hold tenuous land rights to their homes and businesses fear exploitation and expropriation by the government or large businesses. Strengthened property rights may ease religious tensions and allow for the growth and political engagement of a successful Muslim middle class.

“The situation calls for rebuilding and cultivating East African resilience in the face of radical messages and violent behavior.”

Education is also key. Muslim-dominated regions of East Africa lag behind in the number and quality of schools and teacher-to-student ratios. Politically, even small, quick improvements to existing facilities in these regions could build goodwill. Longer term, more Muslim youth should be targeted for scholarships to balance the effects from external ideological influences. Such educational opportunities will also enable them to fill subsequent leadership roles in the broader society, facilitating greater integration.

Practice due process

Governments must also understand that perceptions matter when countering radical ideology. Individuals who stir others to violence are certainly a threat to stability. However, if the public does not believe that legal processes are being followed, then police actions can further fuel support for radicals and their messages. Adhering to the law reinforces its value in the minds (and actions) of these marginalized communities, both as a source of protection and as a demarcation of illegality.

Governments should thus avoid expansive legal actions that have a weak basis or are likely to fail in court. Instead, they should focus on improving law enforcement procedures, evidence collection, and building prosecutorial capacity. When authorities do not have sufficient grounds to prosecute incendiary Muslim leaders or entities, arrests will only be perceived as harassment and counterproductively burnish extremists’ claims of victimization.

Extrajudicial police action must also stop. The government should instead support transparent, credible investigations by independent experts to evaluate claims that Islamic leaders were killed by anyone connected to the state or political leadership. Making these findings public may rebuild some element of trust in the government.

In aggregate, these efforts should not myopically focus on particular individuals who may come and go irrespective of the wider resonance of their views. Instead, they must delegitimize the ideology of violent extremism itself.

Notes

- ⇑ “Al Shabaab in Somalia still a threat to peace in spite of decline—UN,” defenceWeb, August 14, 2012.

- ⇑ “Uganda arrests 19 tied to suspected terror attack plot,” CBC News, September 14, 2014.

- ⇑ “Situation Report: Tanzania: Video Shows Possible New Islamic State Affiliate,” Stratfor Web site, May 18, 2016.

- ⇑ Ryan Cummings, “Al-Shabaab and the Exploitation of Kenya’s Religious Divide,” IPI Global Observatory, December 2014.

- ⇑ Anneli Botha, “Radicalisation in Kenya: Recruitment to al-Shabaab and the Mombasa Republican Council,” ISS Paper 265, September 2014.

- ⇑ Terje Østebø, “Islamic Militancy in Africa,” Africa Security Brief No. 23 (Africa Center for Strategic Studies, November 2012), 4. Chanfi Ahmed, “Networks of Islamic NGOs in Sub-Saharan Africa: Bilal Muslim Mission, African Muslim Agency (Direct Aid), and al-Haramayn,” Journal of East African Studies 3, no. 3 (November 2009), 426–437. Ioannis Gatsiounis, “After Al-Shabaab,” Current Trends in Islamist Ideology 14 (December 2012).

- ⇑ David Ochami, “How fiery cleric Rogo developed, propagated extremism,” The Standard, September 2, 2012.

- ⇑ Anne Robi, “Muslim Clerics Call for New Census Team,” Tanzania Daily News, June 4, 2012.

- ⇑ Ahmed, 430–431. “Muslim clerics warned against hate sermons,” The Citizen, January 7, 2013.

- ⇑ Andre LeSage, The Rising Terrorist Threat in Tanzania: Domestic Islamist Militancy and Regional Threats, Strategic Forum No. 288 (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, September 2014).

- ⇑ “Interview: Vali Nasr,” PBS “Frontline” Web site, available at <http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/saudi/interviews/nasr.html>.

- ⇑ Ben Hubbard, “A Saudi Morals Enforcer Called for a More Liberal Islam. Then the Death Threats Began,” The New York Times, July 10, 2016.

- ⇑ Gatsiounis, 74.

- ⇑ Katrina Manson, “Extremism on the rise in Zanzibar,” Financial Times, December 28, 2012.

- ⇑ Ahmed, 427.

- ⇑ “Africa Muslim Agency Sets Up College in Zanzibar,” Panafrican News Agency, July 26, 1998.

- ⇑ Kenyan Somali Islamist Radicalisation, Africa Briefing No. 85 (Nairobi/Brussels: International Crisis Group, January 2012), 5, 11.

- ⇑ Ahmed, 434–435.

- ⇑ Patrick Mayoyo, “Kenya Muslims Say No to US School Funds,” The East African, February 23, 2004. “Treasury Announces Joint Action with Saudi Arabia Against Four Branches of Al-Haramain In The Fight Against Terrorist Financing,” U.S. Department of the Treasury press release, January 22, 2004.

- ⇑ “Kuwaiti Charity Designated for Bankrolling al Qaida Network,” U.S. Department of the Treasury press release, June 13, 2008.

- ⇑ Joseph Krauss and Megan Lindow, “Islamic Universities Spread through Africa,” Chronicle of Higher Education 52, no. 44 (July 2007), 33–37.

- ⇑ Kenya’s Youth Employment Challenge, UNDP Discussion Paper (New York: United Nations Development Programme, January 2013), 64.

- ⇑ Issa Yussuf, “Zanzibar Pushes to Curb Unemployment,” Tanzania Daily News, November 24, 2014.

- ⇑ Tanzania Mainland Integrated Labour Force Survey 2014: Analytical Report, Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics (2015), 83.

- ⇑ See “Economy: Personal Economic Conditions: Your living conditions vs. others,” under Afrobarometer Round 5 (2010–2012): Kenya and Afrobarometer Round 4 (2008–2009): Kenya, Afrobarometer: Online Analysis.

- ⇑ Liat Shetret, Matthew Schwartz, and Danielle Cotter, Mapping Perceptions of Violent Extremism: Pilot Study of Community Attitudes in Kenya and Somaliland (New York: Center on Global Counterterrorism Cooperation, 2013).

- ⇑ Mohammed Ali and Seamus Mirodan, “Killing Kenya: People & Power investigates allegations that Kenya’s police are involved in extra judicial killings,” Al Jazeera, September 23, 2015.

Abdisaid M. Ali is the Regional Political Advisor for the Office of the European Union Special Representative for the Horn of Africa with a specific focus on extreme violence. The views set out in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union.