US legal and military justifications for conducting attacks in Somalia have evolved recently, leading to a surge in airstrikes. Could the same precedent be used elsewhere in Africa?

Somalia, Libya, where next? Credit: US Army/Richard Bumgardner.

In March 2016, after weeks of gruelling exercises, a couple hundred al-Shabaab recruits marched in formation in front of their officers. The newly-minted graduates were in Raso Camp, about 120 miles north of Mogadishu, preparing for a large-scale offensive on a nearby drone base.

But that attack never took place. Instead, American planes conducted two flyovers, releasing three precision-guided missiles on each run. Within minutes, scores were killed – as many as 150 according to some sources – and many more were injured. Nearby cattle-herders recounted scenes of carnage and confusion as militants collected their dead comrades’ bodies as the camp burned around them.

According to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, the US had just launched its deadliest ever airstrike.

This wasn’t the first air operation the US had conducted in Somalia. In fact, 18 others preceded it. But this was the first strike in which the US invoked self-defence in the face of an “imminent threat”. And since Raso Camp, this justification has been used on six further occasions.

The US, it seems, has found a legal tool that provides grounds for easier and more expansive military operations in Somalia, and it may not stop there.

[Al-Shabaab has changed its tactics. AMISOM must do so too]

Entering Somalia

For many years, US involvement in Somalia was synonymous with the failed 1993 operation in which 19 US soldiers and hundreds of Somali citizens died in a failed raid in Mogadishu. This incident, immortalised in the Hollywood blockbuster Black Hawk Down, led the US to withdraw and made it wary of intervening in foreign conflicts.

That changed after the September 11 World Trade Centre attacks in 2001. In a few short years after this, the US military found itself in Afghanistan and Iraq, with covert counter-terror teams expanding operations even further around the globe.

In 2006, Somalia’s civil war led to the emergence of al-Shabaab, a militant Islamist group dedicated to waging war against the Somali government and its political and military allies. And so, 13 years after it had retreated, the US had reason to be interested in Somalia once more. In 2007, it re-entered in support of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), a regional peacekeeping mission tasked with fighting al-Shabaab and supporting the fledgling Somali government.

The US launched its first air operation in Somalia in that same year, targeting the alleged organisers of the long-past but hard-remembered 1998 embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania. The attack, conducted by a manned aircraft, hit four villages and a training camp near Ras Kamboni in the south of Somalia, killing up to ten Islamist militants. One of those was Fazul Abdhullah Mohammaed, a well-known figure within al-Qaeda, a group to which al-Shabaab would officially pledge allegiance in 2012.

The US justified this strike using the same Authorisation of Military Force (AUMF) that was used to invade Afghanistan after September 11. This authorisation was initially signed into law to give the US president the flexibility “to use all necessary and appropriate force” to hunt down non-state actors complicit in the 9/11 attacks. However, since its inception, the AUMF has been re-interpreted to justify lethal force against actors and in places far away from its original intended jurisdiction.

In the case of Somalia, the argument was made that specific al-Shabaab leaders had pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda, which planned the September 11 attacks. This justification received little scrutiny partly because there were relatively few air operations planned in Somalia. However, more recently, the number of strikes has risen. Moreover, the justification has evolved further.

Whereas before, US officials had to show some sort of connection between the proposed targets and those behind 9/11, now force is justified through “unit self-defence” as in the case of Raso Camp. Under this justification, troops can respond to any threats of “imminent force” posed to either US or allied forces. And with the US considering AMISOM an allied force, this means any enemy plotting against AMISOM can be considered equivalent to one planning to attack US troops.

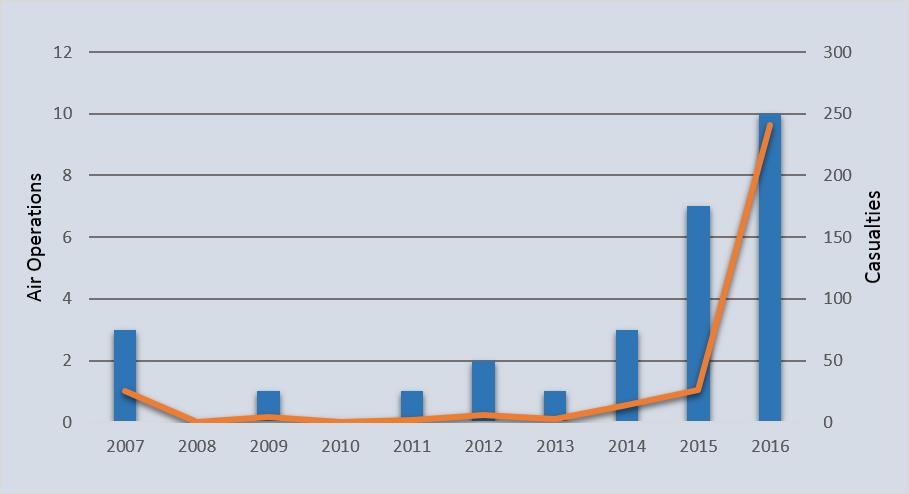

This new understanding provides significant leeway for conducting strikes that may or may not be of immediate tactical importance, such as in the case of Raso Camp. And already, the number of strikes has increased sharply to the point that 60% of all US strikes in Somalia have occurred in 2015 and 2016 alone.

The increasing pace of US airstrikes in Somalia. Source: The Bureau of Investigative Journalism. Note: Casualties are the average of low and high estimates.

[The few known knowns about US drone policy in Africa]

Mission creep?

As well as Somalia, the administration of President Barack Obama has used the AUMF to pursue militants in Yemen, Syria and Iraq. And with so-called Islamic State (IS) claiming affiliates in the likes of Nigeria, Libya and Bangladesh, the next US president has disturbingly broad legal powers to extend the geographic scope of US strikes even further. America’s political and tactical interests of course vary widely from place to place, but if it did want to expand its operations in various parts of Africa in the future, it would have precedents to follow.

The US simply has to follow the three-step pattern of: 1) Identify a connection between a target group and al-Qaeda; 2) Use the AUMF to initiate assaults, support an ally fighting it, or send in military personnel; and then 3) Use the justification of “unit self-defence” to sustain or expand strikes.

In West Africa, the US already operates unarmed surveillance drones out of Cameroon, Niger, and Burkina Faso, while it has deployed military advisers to Nigeria to help combat Boko Haram, a militant Islamist group that pledged allegiance to IS in March 2015. Elsewhere in the Sahel, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and other Islamist groups are still present and operative. Meanwhile in North Africa, the US conducted its first public airstrikes in Libya against Islamic State just earlier this month.

[What led IS to announce a new Boko Haram leader? Here are two clues from its communications.]

[Boko Haram, Islamic State, and the underlying concerns for West Africa]

While far removed from 9/11, these regions could be new frontiers in US operations, legally enabled by the AUMF and justified by the notion of unit self-defence. Without interrogation of these creeping principles, these authorisations combined with the growing influence of IS and other groups with historic ties to al-Qaeda could mean that the so-called War on Terror not only stretches on for generations but extends to other areas of Africa and beyond with little oversight.

Austin Brush studies International Relations at Tufts University in Boston, specialising in security and governance in East Africa.