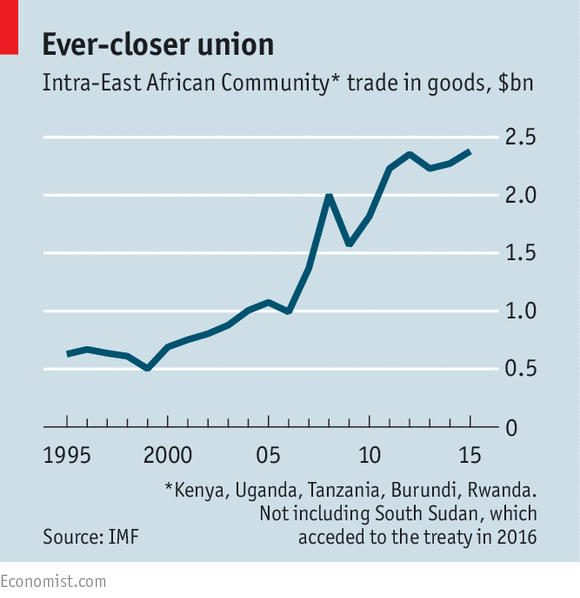

WHEN the first East African Community (EAC) collapsed in 1977, some in the Kenyan government celebrated with champagne. Since its resurrection in 2000, officials are more often found toasting its success. A regional club of six countries, the EAC is now the most integrated trading bloc on the continent. Its members agreed on a customs union in 2005, and a common market in 2010. The region is richer and more peaceful as a result, argues a new paper* from the International Growth Centre, a research organisation.

Many things boost trade, from growth to international deals. The researchers use some fancy modelling to pick out the effect of the EAC. They find that bilateral trade between member countries was a whopping 213% higher in 2011 than it would otherwise have been. Trade gains from other regional blocs in the continent are smaller: around 110% in the Southern African Development Community (SADC), and 80% in the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA).

Those numbers for the EAC are all the more impressive because the available data stop before the EAC’s common market had properly come into effect. Progress on that front has sometimes stuttered. A 2014 “scorecard” identified 51 non-tariff barriers. Full implementation could double the income gains seen so far, say the researchers. Not surprisingly, it is landlocked Rwanda which would see the biggest benefits. Tanzania, which has dragged its feet on integration, would profit the least.

The researchers are warier of the EAC’s other grand project: creating a common currency by 2024. The impact on trade would be small, they say, and not worth the risks. A study last year by the IMF found that east African economies move out of sync with each other, using exchange rates to absorb shocks. Greater convergence might make a common currency viable; without it, a single currency would mean that wages might have to do the work of adjustment, as Greece has become painfully aware. The euro crisis should give policymakers pause for thought.

Political convergence matters too. Recent squabbles over railways and an oil pipeline show the difficulty of coaxing headstrong leaders to cooperate. But interdependence has reduced the risk of war, the researchers argue. Regional trade blocs make sense for Africa. National economies are small: at market exchange rates, the combined GDP of the EAC, home to 170m people, is less than New Zealand’s. Regional groupings have more clout, and could one day form a continental free-trade area (a planned link-up between the EAC, COMESA and SADC is a start). Then the champagne corks would really start popping.

*‘Regional Trade Agreements and the pacification of Eastern Africa’, Thierry Mayer and Mathias Thoenig, International Growth Centre Working Paper, April 2016