Date: Wed, 22 Jun 2016 00:33:30 +0200

Libya: In the Eye of the Storm

By Lisa Watanabe for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

21 Jun 2016

Irregular migration to Europe and the rise of the so-called Islamic State (IS) in Libya have increased the urgency of restoring order to this oil-rich country. The new unity government will need to impose its authority in a country where localism and armed militias still hold sway. International actors should ensure that their engagement supports the political process and the unity government.

Five years after the fall of Muammar Gaddafi, Libya appears to be taking a positive step towards ending a two-year conflict that has seen the country divided between two rival governments and parliaments, each allied with loose coalitions of armed militias fighting each other. The growing governance and security vacuum this has generated is viewed with increasing alarm by the international community, not least due to the rise of IS in Libya and the country’s role as departure point for migrants hoping to reach Europe. A political solution to the conflict has come to be seen as critical to reducing instability in Libya, as well as preventing the chaos in the county from spilling over further to North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and Europe. Following the signing of a UN-brokered political agreement in December 2015, the creation in March 2016 of a Government of National Accord (GNA), led by the technocrat Fayez al-Sarraj, has thus been met with relief.

Implementing the political settlement will be far from straightforward, however. While the conflict has often been characterized as primarily one between Islamists and their opponents, it is considerably more complex. To be sure, ideology has been a mobilizing factor. However, the conflict has been driven by the competing interests of local groups that have been able to deploy violence for political gain and control over resources. The new GNA will need to reconcile these competing groups as it lays the foundations of new governance structures and stronger state institutions, particularly in the security sector. International support aimed at assisting Libyan authorities in degrading the IS – or, more generally, in stabilizing the country – must be harmonized with the GNA’s efforts to increase its support base and to build sustainable political and state structures.

A Fractured Land

Following the uprisings in neighboring Tunisia and Egypt, a rebellion in Libya brought an end to Gaddafi’s 42-year rule on 20 October 2011, when the country’s leader was captured and killed. The insurrectionists were a medley of brigades grouped together as the National Liberation Army(NLA) and accompanied by individual militias linked to various cities or tribal communities. Some of these militias and brigades were subject to the authority of local councils established to administer liberated cities and regions; others formed their own military councils. They were unified only in their aim of overthrowing Gaddafi, which they succeeded in doing, with the help of the NATO-led mission, Operation Unified Protector, which was mandated under the rather ambiguously worded UNSC resolution 1973 to “take all necessary measures” to protect civilians. Once Gaddafi had been murdered and NATO’s mission ended a week later, the myriad militias and their associated localities became nodes of power with revolutionary kudos.

The National Transitional Council (NTC), the political face of the rebellion and the first interim political authority in Libya, existed alongside these rival constellations of political and military power. Several attempts were made to demobilize and co-opt the militias. In October 2011, a Supreme Security Committee was created to perform provisional policing tasks. It was comprised entirely of personnel recruited from the militias. However, the body itself soon came to represent a threat, allegedly carrying out attacks on Sufi shrines, foreign embassies, and state institutions. In another move to tame the militias, the NTC in March 2012 created a military structure that existed alongside the army, the Libyan Shield, into which whole revolutionary brigades and militias from the NLA were integrated. However, this ultimately meant that they retained their existing chains of command and loyalties and continued to pursue their own agendas, despite being on the state payroll.

Without having successfully reintegrated or demobilized the militias, the NTC set about establishing a new political system. General elections in July 2012 established an interim parliament, the General National Congress (GNC). The National Forces Alliance, a loose coalition of liberals and former regime supporters, held the majority of seats allocated to party lists, followed by Libya’s Islamist political parties, the Justice and Construction Party and the Watan Party. The majority of remaining seats were held by independent candidates, most of whom were allied with Islamist parties. One of the major tasks of the GNC was to draft a constitution within 18 months. After this period, the mandate of the GNC would expire and elections would be held to replace it with a new parliamentary body, the House of Representatives (HoR), from which an elected government could be formed.

The Slide into Civil War

However, between 2012 and 2014, a rift emerged in the GNC that would eventually grow into a civil conflict. Despite their comparatively poorer showing in the elections, compared to liberals and their allies, Islamist political parties were able to join forces with independent parliamentarians to push through controversial legislation. The most divisive piece of legislation was the 2013 Political Isolation Law banning top-ranking Gaddafi-era officials from public service. The legislation appeared to be aimed at prohibiting Mahmoud Jibril, the leader of the National Forces Alliance, and his allies from participating in politics. Moreover, the vote was held with Islamist-aligned militias positioned outside the GNC building. The seeds of Libya’s conflict were further sown when a military offensive,Operation Libya Dignity, was launched by General Khalifa Haftar in May 2014 against militias in Benghazi and Tripoli that were aligned with Islamist parties, following his earlier unsuccessful calls for a coup.

It was against this backdrop that the June 2014 general elections went ahead as scheduled, despite the GNC having missed the deadline for establishing a constitution. Once again, liberals and former regime supporters gained a majority of parliamentary seats. This time, however, a significant number of them moved to Tobruk to set up the HoR instead of in Tripoli or Benghazi, as foreseen in the NTC’s transitional road map. The remaining GNC parliamentarians in Tripoli accused them of orchestrating a coup against the “revolution” and declared the HoR to be illegitimate. Militias supporting GNC parliamentarians then launched a counter-offensive, Libya Dawn, against Operation Libya Dignity.

Libya hence was divided into two broad coalitions – the Dawn coalition of militias aligned with the GNC in Tripoli and its government, on the one hand, and the Dignity coalition aligned with the HoR in Tobruk and its government, on the other. While the HoR’s government was recognized by the majority of the international community, it has struggled to gain authority within the country. Meanwhile, the GNC’s claim to a legitimate right to rule was strengthened by a Libyan Supreme Court ruling on 6 November 2014 declaring the June elections null and void, due to parts of the electoral law being unconstitutional. It continued to attempt to govern from Tripoli. Nevertheless, even though it controlled most state institutions, including the Central Bank and the National Oil Corporation, it was unable to prevail.

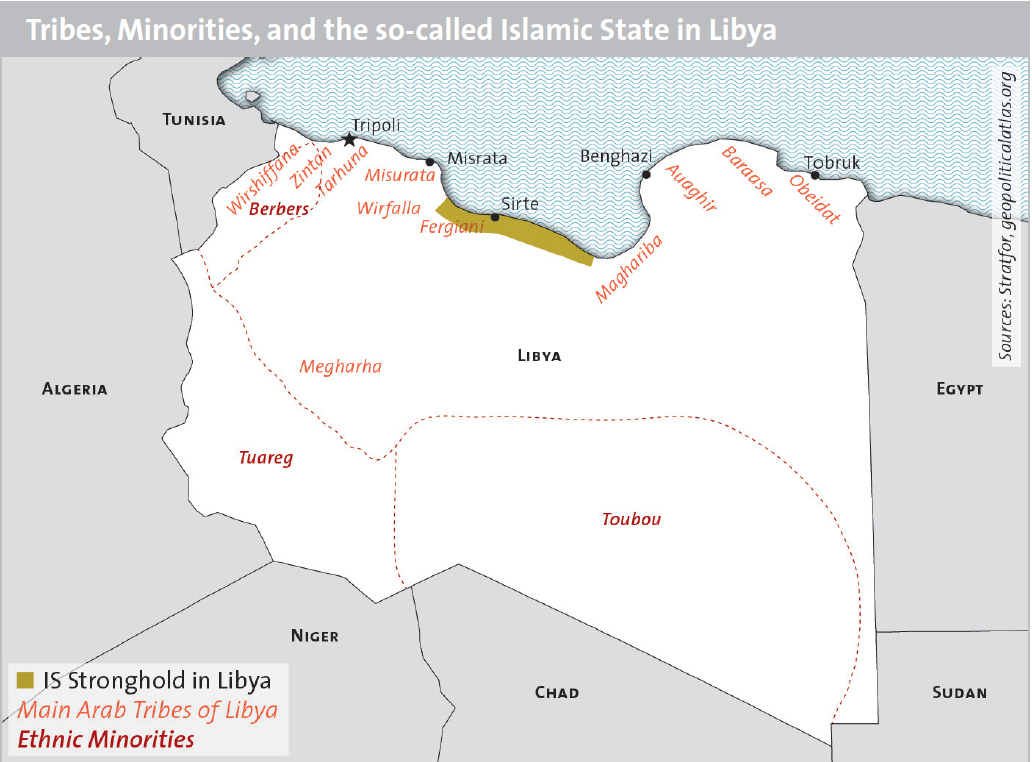

The Dawn coalition includes the Misratan militias, the Libyan Muslim Brotherhood, former members of the once al-Qaida-affiliated Libyan Islamic Fighting Group who are now politicians and leaders of militias, as well as Berber tribes. In the Dignity camp are those who oppose Islamists, not so much due to ideology as out of mistrust about their intentions with regards to purging politics and the public sphere of remnants of the old regime. It comprises elements of the Gaddafi-era armed forces, the Zintani militias, and eastern Libyan tribes in favor of federalism. The divisions are thus local – connected to the interests of powerful localities and tribal communities – as well as, to a lesser extent, regional and ethnic.

At first glance, these two loose coalitions appear to reflect ideological divisions. However, the conflict is driven more by interests and competition for relative power and resources than by ideology. Haftar has sought to depict his campaign as one against Islamists. The regional dimension of the conflict has also served to reinforce this characterization. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Egypt have backed Haftar and the government in Tobruk as part of their broader objective of weakening political Islam in the region, launching air strikes and allegedly providing equipment to strengthen Haftar’s and Dignity’s position. The Libyan Dawn coalition, in turn, has been favored by countries perceived to be pro-Islamist, namely Turkey, Qatar, and Sudan, which have allegedly provided it with weapons. Meanwhile, British, French, US, and Russian special forces have been providing support to the Tobruk government. However, this support appears to have been aimed primarily at halting the spread of the IS. They have since been joined by Italian special forces.

Gaddafi’s Legacy

Post-conflict dynamics notwithstanding, Gaddafi’s deliberate efforts to keep governance and state structures weak set the stage for the prevalence of localism and the emergence of militias. In Gaddafi’s version of popular democracy – the Jamahiriya – the people were represented by popular congresses elected at the local level, which in turn selected popular committees as executives. No political parties or parliament existed. While the popular congresses purposely cut across tribes to curb the power of tribal notables, tribal loyalties remained significant. Gaddafi himself relied on tribal loyalties to shore up support through a system of patronage facilitated by oil and gas revenues. Moreover, tribal allegiances would often determine the outcomes of elections to the popular congresses. Local and tribal affiliations, thus, were politically important even during the Gaddafi era.

Having come to power in 1969 through a military coup, Gaddafi also sought to prevent the development of a strong police or army, thwarting the development of an esprit de corps by regularly rotating the leadership and using tribal patronage to foster rivalries and prevent cohesion. Gaddafi relied on a parallel set of security institutions to protect the regime: the Intelligence Bureau of the Leader, the Military Secret Service, the Jamahiriya Security Organization, and Purification Committees tasked with identifying subversive elements in the popular committees. Gaddafi assigned key posts in these structures to individuals with family or tribal ties to the Gaddafi clan.

It was not surprising, then, that the army and police forces disintegrated when the rebellion began, that local communities and tribes were crucial mobilization factors in the 2011 civil war and beyond, or that military forces emerged at the local level, with those in the cities of Misrata and Zintan playing particularly important roles in the rebellion. Those tribes that had been oppressed under Gaddafi, notably the eastern tribes of oil-rich Cyrenaica and the Berber tribes of the northwest, were amongst the first to join the rebellion and have advanced their political calls for federalism and greater representation, respectively, ever since.

Exploiting the Security Vacuum

Amid the chaos in Libya, the so-called Islamic State as well as al-Qaida-affiliated groups have gained ground in the country. The prospect of the IS in particular expanding its presence in Libya is of increasing concern, while the unity government has been focused on the immediate task of establishing its presence and authority in Tripoli. The number of IS militants in Libya is unknown; estimates range from 2,000 to 10,000. The actual number is likely to be somewhere in the middle, around 5 – 6,000. This would make the IS one of the largest armed non-state groups in Libya, which has led some observers to qualify it as a third force, as it is not aligned with either the Dawn or the Dignity coalitions. However, its limited territorial control – which includes only the coastal city of Sirte and its environs – suggests that this assessment of its strength may be exaggerated.

The group’s presence is, nevertheless, worrisome. In addition to its efforts to hold on to territory and expand eastwards into Libya’s “oil crescent” in order to disrupt the state’s oil revenue, it already seems intent on using the country as a base from which to destabilize Tunisia and Egypt. Both of which provide opportunities to target symbols of the respective regimes, as well as to carry out high-profile attacks on tourists. Its destabilizing effect may even reach beyond Libya’s immediate regional neighbors to Europe. Libya could also serve as a training ground and transit country for IS militants planning attacks in Europe, particularly if European foreign fighters should choose to go to Libya as an alternative to Syria and Iraq or flee from Syria and Iraq to Libya, and eventually return home. Understandably, pressure has been building to find a political solution to the conflict that would facilitate more concerted international efforts to eliminate IS in Libya.

In addition to the IS, people smugglers have been able to exploit the governance and security vacuum in the country by organizing the sea crossing for migrants seeking to enter Europe irregularly. Libya constitutes a key transit state on the Central Mediterranean migration route, a major route that comprises the sea passage from North Africa to Europe. While the number of migrants taking this route decreased in 2015, it is expected to rise again in 2016. This would place Italy, and perhaps Malta, under severe strain again. In June 2015, the EU launched EUNAVFOR, a maritime mission to deter and disrupt people smuggling from Libya. However, to date, it has only been able to operate in international waters. The EU would like to see it operate in Libyan territorial waters and on Libyan beaches to be more effective. However, since the Libyan GNA is unwilling to give permission at this stage, international actors, including the EU, are considering alternative initiatives.

Stabilizing Libya

While the new interim GNA may facilitate action against the IS and people smugglers, since there would be a single and, it is hoped, more effective political authority that would welcome some forms of international assistance, it faces formidable challenges. Its first task must be to widen its domestic support base. The political settlement that led to the GNA was reached under considerable pressure from the UN and the EU. Not all constituents of the two broad coalitions – Dawn/GNC and Dignity/HoR – supported the negotiations, and these elements have high “spoiler” potential. The GNA still lacks endorsement by the HoR as a whole, as the UN-drafted political agreement did not require that both parliaments vote on it before it could be signed. Continued opposition to the deal in the HoR is partly linked to the question of whether Haftar should become head of the armed forces, which the HoR had made him. Haftar too could act as a spoiler. His unilateral assault on the IS in Sirte, which he began in April 2016 in spite of the GNA’s announcement that it intends to create an anti-IS task force, appears de- signed to strengthen his own political bar- gaining power. This recent development is symptomatic of two additional challenges the GNA faces, namely reducing the use of armed force for political gain and avoiding a situation where the fight against the IS further increases the country’s fragmentation.

Engaging tribes will be critical to establishing broader political support. Gaining the support and trust of eastern tribes will be especially important to undermining Haftar’s capacity to act as a spoiler. Tribal leaders are likely to be particularly concerned about the distribution of power within state institutions, as well as political and economic governance structures. The GNA will also need the support of key militias to carry out basic government tasks and to foster national reconciliation. Since the majority of the militias are tied to localities, the role of city councils will be important as well. The efforts to integrate key militias that support the GNA into formal policing and military structures should not be ruled out as futile. It is important to remember that under earlier attempts to tame them, they were only integrated into provisional or parallel security structures. They were, therefore, not sufficiently incentivized to lay aside their parochial interests. Establishing cohesion in security structures would be a tremendous challenge, to be sure. Tying their willingness to combat the IS under the coordination of the GNA’s anti-IS task force could be a first small step in this direction.

The GNA must also avoid appearing as the puppet of external actors. This means that international actors should focus on supporting the implementation of the political settlement and the GNA. While the UK, France, the US, and Italy have been increasing the presence of their special forces in the country, and the US has even carried out air strikes against IS targets, any counterterrorism support they provide should be tied to support for the political process and the GNA, ideally with the backing of regional powers that have a stake in conflict in Libya. As such, international assistance in the form of training, intelligence, and equipment should be channeled and coordinated through the GNA, though even this is not without its risks. Broader stabilization efforts would be best focused on support for mediation, ceasefire monitoring, and capacity-building, especially with regard to building cohesion within national police and armed forces.

About the Author

Dr. Lisa Watanabe is a Senior Researcher at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich. She is the author of several publications, including ‘Borderline Practices – Irregular Migration and EU External Relations’.