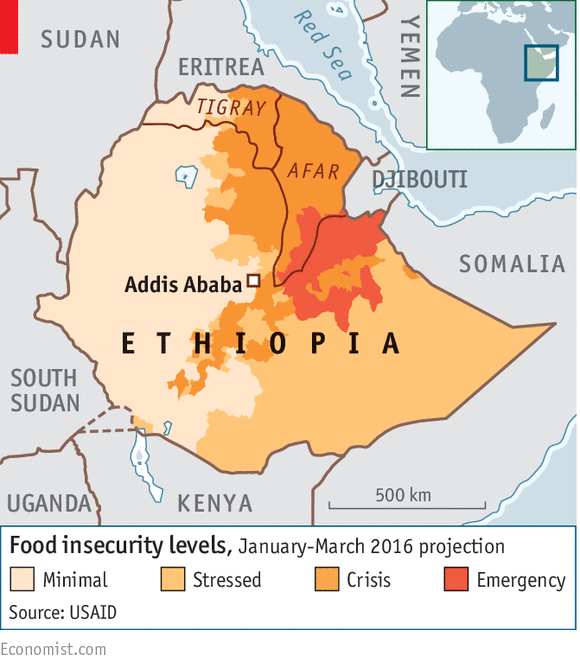

“THE animals die first” is a common refrain from many Ethiopians living in Tigray and Afar, two northern states, as the country experiences its worst drought in decades. Crop production in these regions has dropped by 50% or more in some areas, and failed completely in others. Hundreds of thousands of domestic animals are reckoned to have perished.

The rapidly changing skylines of Ethiopia’s modernising cities notwithstanding, about 80% of its population still live off the land. Yet despite the drought there are not yet scenes reminiscent of the famine of 1983-84 when as many as 1m people died.

That reprieve may not last. Those working for NGOs, which are now scrabbling to raise funds for relief, point out that in previous dry spells, hunger intensified from April onwards because by then people have eaten through their last food stocks or what little was harvestable. “The present situation here keeps me awake at night,” says John Graham, the country director for Save the Children, a charity.

Unlike in 1983, when brutal government policies increased the number of deaths, Ethiopia’s present rulers have done much to mitigate the impact. Their Productive Safety Net Programme provides jobs for about 7m people who work on public-infrastructure projects in return for food or cash. There are also a national food reserve and early warning systems throughout the woredas, local-government districts. Ethiopia even managed to accelerate the building of a new railway line—the country’s only one—to bring food supplies from Djibouti on the coast of the Horn of Africa.

But the country’s ability to help itself may soon reach its limit. Estimates of the number of people affected by drought doubled between June and October in 2015 to 8.2m, and are now pushing beyond 10m (of a population of about 100m). The government faces criticism for not acknowledging sooner that it needs help.

Ethiopians—both official and lay—are sensitive about their ancient, diverse country’s persistent association with misery and pestilence, while equally proud of its economic turnaround. There is also a sense that the government has not been found wanting with this drought; rather that it has simply encountered events beyond its control. The El Niño phenomenon is causing unusually heavy rains in some parts of the world and drought elsewhere.

Herein lies a challenge for Ethiopia: it is competing for international funds with other grave humanitarian crises, such as the wars in Syria and Yemen, and the international migrant emergency. Moreover, the international system’s cogs started turning late, after the government initially tried to go it alone. Ethiopia may also be up against donor fatigue. The estimated $1.4 billion needed to combat the drought’s impact remains less than half funded. Further concerns stem from the possibility that El Niño will also affect Ethiopia’s next rainy season. The UN reckons such a situation could result in more than 15m Ethiopians suffering food shortages, acute malnutrition or worse by mid-2016.