Rwandan President Paul Kagame (left) and Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari attend this year's African Union Peace and Security Council summit. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, January 30, 2016. (Minasse Wondimu Hailu/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

The Peace and Security Council of the African Union (PSC) is the most important African institution for the day-to-day management of peace and security issues facing the continent. It is the PSC, for example, that coordinates the AU’s conflict management strategies, decides when to authorize peace operations, rules on how to interpret “unconstitutional changes of government,” and determines when to impose sanctions against recalcitrant AU states.

Yet, at the last AU summit, under the headline banner: “2016: African Year of Human Rights,” African states elected arguably the most authoritarian cohort of countries ever to sit on the PSC. What consequences this will have for peace and security on the continent, as well as the AU’s relations with its principal external partners, remains to be seen.

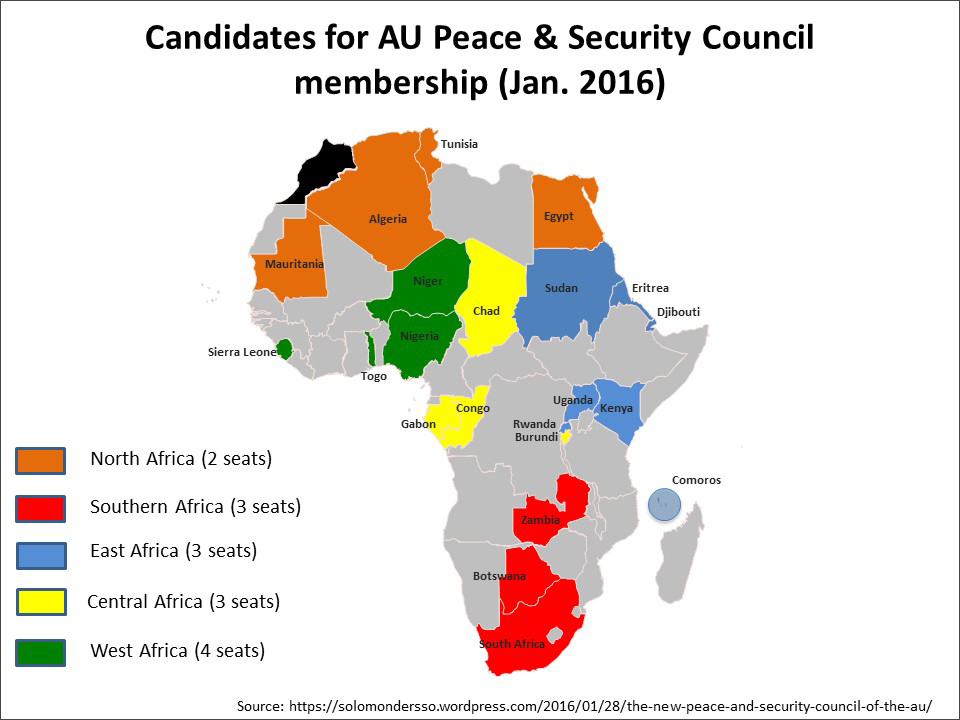

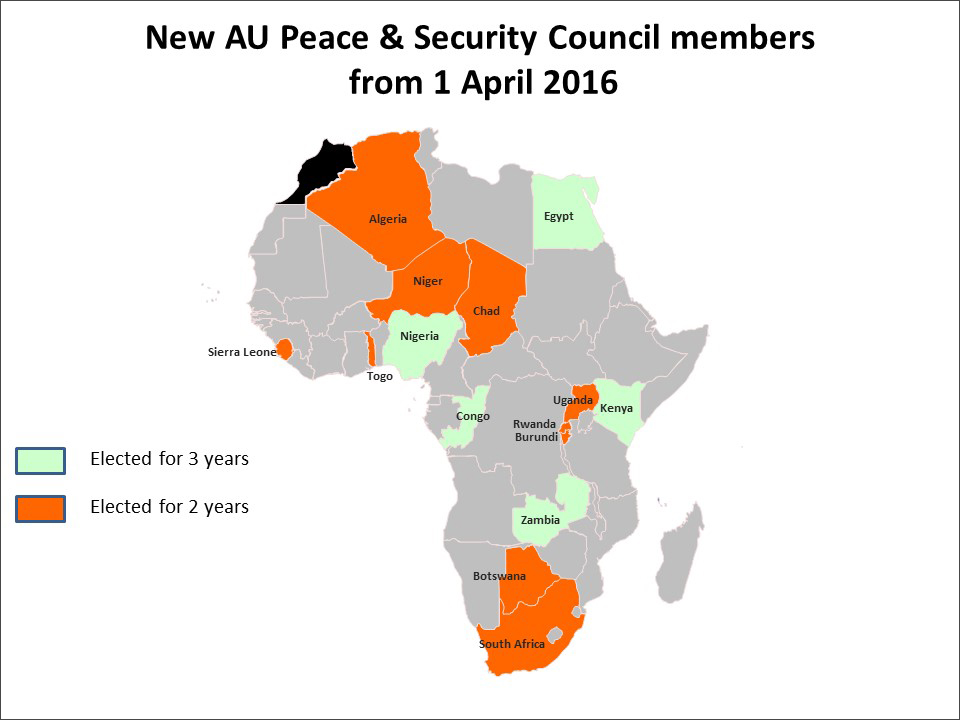

The PSC is comprised of five members elected for three-year terms and 10 members elected to serve for two years. This month, 15 AU members assumed their seats on the PSC following their election during the AU summit in January 2016. It is only the second time since the PSC was established in 2004 that all 15 members were up for re-election at the same time (the previous occasion being 2010). With this new cohort of members, 40 of the AU’s 54 member states have now served at least one term on the PSC.

Retiring members of the PSC are eligible for immediate re-election, and in this instance seven states were duly re-elected to serve on the Council (Algeria, Burundi, Chad, Niger, Nigeria, South Africa, and Uganda). Nigeria is the only state that has served consistently on the PSC since 2004. This is in spite of the AU’s explicit rejection of the idea of particular states holding permanent seats on the PSC. It was also notable that Africa’s five regions adopted different approaches to the PSC elections: the north, eastern, and central regions all held contested elections for their allocated PSC seats whereas west and southern Africa put forward uncontested candidates.

The latest PSC elections sparked some criticism, particularly over Burundi’s re-election while the summit simultaneously debated whether to deploy AU peacekeepers there. Since then, however, the composition of the current PSC has attracted relatively little commentary. Unfortunately, the current cohort is notable because it illustrates how most AU members are willing to set aside their own rules; in this case, some of the official criteria that should influence which states get elected onto the PSC. This is a long-standing problem for the AU, as I have noted elsewhere.

The official rules governing the conduct of the PSC are set out in the 2002 Protocol Relating to the Establishment of the Peace and Security Council of the African Union. The Protocol includes several references to factors that should be considered relevant when electing AU member states to serve on the PSC. For example, the Preamble emphasizes the link between democratic governance, human rights, the rule of law, and peace and stability in Africa. Article 3(f) states that one of the Council’s objectives is to “promote and encourage democratic practices, good governance and the rule of law, protect human rights and fundamental freedoms, respect for the sanctity of human life and international humanitarian law, as part of efforts for preventing conflicts.” Similarly, Article 4(c) states that one of the PSC’s founding principles is “respect for the rule of law, fundamental human rights and freedoms, the sanctity of human life and international humanitarian law.” Article 5(2) explicitly sets out the criteria for membership of the PSC, which include a commitment to uphold the principles of the AU and respect for constitutional governance as well as the rule of law and human rights. Finally, Article 5(4) states “There shall be a periodic review by the Assembly to assess the extent to which the Members of the Peace and Security Council continue to meet the requirements spelled out in article 5(2) and to take action as appropriate.” I’m aware of no evidence that such a review has ever taken place.

And yet the latest PSC elections repeatedly contradicted the Protocol’s directives. For example, seven current PSC members routinely deny their citizens various forms of political rights and civil liberties. They are “Not Free,” according to Freedom House’s Freedom in the World 2015 report (Algeria, Burundi, Chad, Congo, Egypt, Rwanda, and Uganda). Similarly, six PSC members are in the bottom half of the 54 AU members ranked by the Mo Ibrahim Index of African Governance 2015 (in order, Chad, Congo, Nigeria, Burundi, Togo, Niger). Seven PSC members were in the bottom third of the world’s most corrupt states as measured by Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index 2015 (in order, Burundi, Chad, Congo, Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria, Sierra Leone). And 11 of the current PSC cohort are among the worst 50 states in the world for human rights and rule of law according to the Fragile States Index 2015 (in order, Egypt, Chad, Nigeria, Burundi, Uganda, Congo, Rwanda, Togo, Algeria, Niger, Kenya).

These comparative national indicators are important. But it is also notable that the rule of law is under threat even in one of the PSC states that scores well on such governance indicators. Last week, South Africa’s constitutional court ruled that President Jacob Zuma had failed to uphold the country’s constitution when using public funds to renovate his private residence. The rule of law also looked distinctly shaky when South Africa’s Supreme Court of Appeal ruled that the government failed to carry out its domestic and international legal duty to arrest Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir when he had visited South Africa to attend the AU summit in June 2015.

The current crop of PSC members is therefore arguably the most autocratic yet, with the potential exception of the 2012-13 cohort. It remains to be seen how they will perform over the next 2-3 years. But such an authoritarian-heavy Council raises at least three significant questions. First, is it more evidence of a growing complacency among African leaders about the need for good governance and the erosion of democratic institutions in Africa? Second, will it have consequences for how external partners continue to engage with the AU in general and the PSC in particular? And, third, is it time, as Dr. Solomon Dersso has argued, to disqualify some of Africa’s worst governed regimes from running for election to the PSC?

Paul D. Williams is Associate Professor of International Affairs at George Washington University. _at_PDWilliamsGWU.