AT 2pm in the tiny African state of Djibouti everything stops. As the sun burns high in the sky people retreat to their homes, save for a few men lying in the shade of colonial-era walkways, chewing qat leaves that bring on a hazy high. In the soporific heat you would be forgiven for thinking that time had forgotten the New Jersey-sized nation. Yet its quiet stability within the volatile Horn of Africa has made the country of just 875,000 people a hub for the world’s superpowers.

The stars and stripes flutters alongside the runway where military and passenger planes touch down: Camp Lemmonier, America’s only permanent military base in Africa, hosts 4,500 troops and contractors who conduct missions against al-Qaeda in Yemen and al-Shabab in Somalia. The outpost, leased for $60m a year, shares an airstrip with the international airport, although its drones now fly from a desert airfield eight miles away after one crashed in a residential area in 2011.

Djibouti also hosts France’s largest military presence abroad (it still has an agreement to defend its former colony); Japan’s only foreign base anywhere; and Spanish and German soldiers from the EU’s anti-piracy force, who are billeted at the fancy Kempinski and Sheraton hotels. The Saudis and Indians are also rumoured to be interested in establishing outposts, as are the Russians.

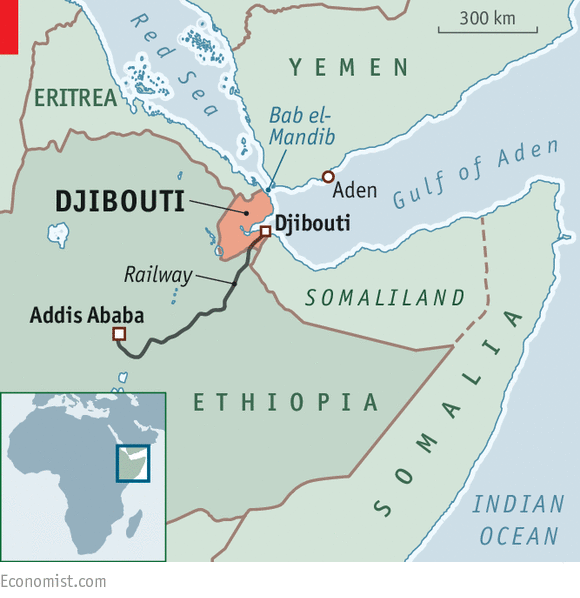

Meanwhile, China is building its first overseas base anywhere in the world in Djibouti, for which it will pay a more modest $20m in rent annually. It is supposedly nothing more than a logistics hub for anti-piracy operations and evacuating citizens from hotspots like Yemen, just 20 miles away across the Bab el-Mandib strait. Some Western officials fear that China may have bigger plans, however. It might in the future be awkward to have countries that do not always see eye-to-eye running military operations out of the same crowded space.

The tiny desert state wants to be more than a superpowers’ playground, though; it has ambitions to become a Dubai or Singapore at the gateway of the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. “We don’t have anything else but location,” says Robleh Djama Ali, the head of business development at the Djibouti Ports and Free Zone Authority. The country’s lack of natural resources may be coincidental, but its fortuitous geography, wedged between Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia, is no accident. France wanted a port to rival Aden, Britain’s colony on the other side of the Red Sea. It has been desirable more recently too. The terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001 brought the American military. Somali pirates brought EU soldiers. The Ethiopia-Eritrea war from 1998 to 2000 robbed Ethiopia of access to its smaller neighbour’s ports. Now 90% of Ethiopia’s imports come through Djibouti, accounting for 90% of its ports’ traffic.

Ethiopia’s double-digit growth over the past decade has rubbed off on Djibouti. Around $9.5 billion of energy and infrastructure projects are under way, including four more ports, two new international airports and two pipelines, and a railway to Ethiopia (the last, ministers promise, is due to open within weeks). Another $9.7 billion of proposals are as yet unfunded. To put this in perspective, Djibouti’s GDP was just $1.6 billion in 2014.

China is the biggest investor, much of it via soft loans. Officials won’t say exactly how much they are in hock to the Chinese, but both the IMF and African Development Bank have warned about its public debt, which is projected to balloon from 60.5% of GDP in 2014 to 80% in 2017. The finance minister, Ilyas Moussa Dawaleh, isn’t concerned: “what we are getting from China is much more important than any other long-standing partner,” he says.

The boom has not benefited everyone. The ports account for a whopping 70% of GDP, but only provide a few thousand jobs. The UN puts unemployment at 60%, though Mr Dawaleh claims it is half that (Djibouti’s data are dodgy). Illiteracy runs at about 45%. The lack of employment is offset by traditional support systems; one worker can support an entire extended family. So the government can buy the loyalty of, say, 30 people by hiring a single bureaucrat.

Dissent still simmers. Opposition figures claim police killed 19 people at a religious celebration in December 2015 (the government says only seven died). A corruption case brought by the government against Abdourahman Boreh, a wealthy businessman who was President Ismael Omar Guelleh’s right-hand man until he questioned his plan to run for a third term in 2011, was thrown out by a British High Court at the start of March. The country is voting on April 8th, but the re-election of Mr Guelleh for his fourth presidential term is a foregone conclusion; the opposition, an unwieldy coalition of seven parties, is fielding two rival candidates.