Date: Mon, 16 May 2016 22:24:09 +0200

Uganda: Museveni has been sworn-in, now what?

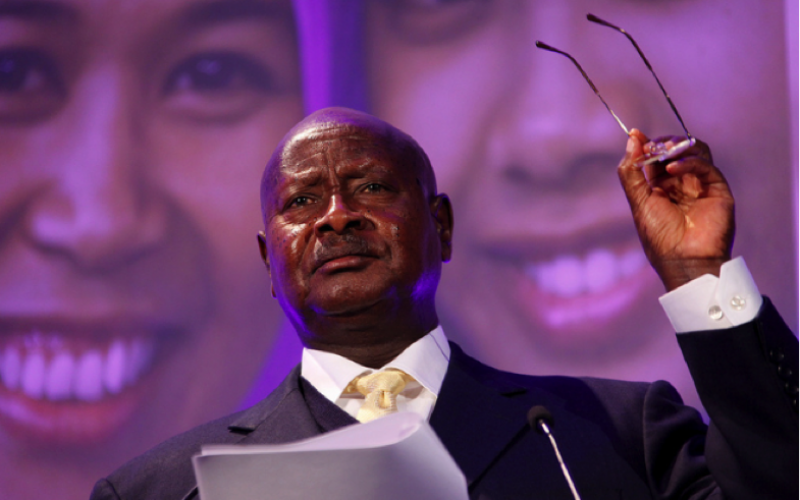

On May 12th, incumbent President Museveni of the National Resistance Movement (NRM) was sworn-in for a fifth term in office, continuing his 30-year rule. The 18th February elections were won with 60.62% of the vote through a combination of popular support, electoral coercion, and intimidation tactics.

The path to victory was far from simple. The incumbent faced notable challenges from Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) candidate, Kizza Besigye, who secured 35% of the vote and from a prominent NRM defector and former Prime Minister, Amama Mbabazi, who secured just 1.8% of the vote, running as the GoForward candidate.

Throughout the electoral process, Besigye was arrested on multiple occasions. Most recently on May 11th , he was arrested after holding a mock inauguration ceremony, as part of his ‘defiance’ campaign, claiming that he had won 52% of the vote. Besigye has subsequently been charged with treason. Also protesting the outcome, Mbabazi contested the results at the Supreme Court, which subsequently ruled in favour of Museveni and his alleged victory.

The European Union and the United States criticised the electoral process, claiming that the Electoral Commission lacked independence and that security crackdowns and mass arrests had created an atmosphere of intimidation.

But like it or not, Museveni is set to rule as President for at least the next five years.

Factionalism

During his term, Museveni will have to manage various factions within the NRM. The electoral process exposed the party’s increasing factionalism to the point where Mbabazi felt he had a genuine chance of securing the presidency by drawing on the support of disillusioned party members. With 19 cabinet ministers having lost their seats, the rebuilding of the cabinet may prove an important tool for managing various internal divisions. Yet, selection for such positions amidst internal competition risks generating controversy and damaging Museveni’s influence within the NRM.

Furthermore, uncertainty over the future leadership of NRM may accentuate tensions within the party over the next five years in a potential transition phase. By the 2021 elections, the President will be constitutionally too old to run for office. Rumoured successors are his son and head of the Special Command Forces, Muhoozi Kainerugaba and his wife Janet Museveni, formerly the Minister for Karamoja Affairs. But, such figures are neither particularly popular within the NRM or amongst the public, meaning that their increasing power within the party could undermine its unity. Similarly, other potential leaders may be seeking to improve their own prospects of becoming president by attempting to secure the support of various factions.

Alternatively, Museveni could in theory run for office again if the constitution were to be altered. With NRM controlling 268 seats in the 10th Parliament, the party has a majority of more than two-thirds, allowing them to change the constitution. But given the increasing levels of conflict following Museveni’s continued tenure, by 2021 dissent could be substantially higher, meaning that running yet again increases the risk for a Burundi-type scenario in Uganda.

Politics and petroleum

If Museveni is to maintain legitimacy over the next five years, employment levels, particularly amongst the large young population, need to substantially improve. A lack of inclusive economic growth was one of the main threats to Museveni staying in office. The party’s so-called “steady progress” program will not be enough to resolve the issue and achieve the goal of middle-income status by 2020.

One notable nascent economic sector that may be used to invest in economic diversification is the oil sector. Uganda has 2.5 billion barrels of oil reserves, production of which is expected to begin in 2018. Using oil revenues to invest in growing the manufacturing sector, would facilitate increased levels of employment.

However, investing in long-term inclusive economic growth may not be in Museveni’s political interests. The political return on investment would unlikely be substantial enough in the short-term to fix economic woes, such as the depreciating Ugandan shilling and unemployment, in order to improve his legitimacy.

Instead, a major boost in government revenues from oil production would potentially help Museveni to buttress his patronage networks. Such well-oiled networks would enable him to buy-off opposition figures (particularly in areas of western and eastern Uganda) and strengthen internal party cohesion, establishing a pseudo-legitimacy. Patronage has proved a relatively successful tool for Museveni thus far and is one strategy he is likely to continue to use to govern the political space.

East Africa relations

Regionally, Uganda’s oil is also proving to be of strategic importance in determining political dynamics. Originally, Museveni had agreed to establish a pipeline through Kenya to export oil, but has since then instead agreed to a pipeline through Tanzania. Owing to this, tensions between Tanzania and Kenya have become more pronounced. By example, President of Tanzania, John Magufuli, may have attempted to publicly embarrass the Kenyan President Kenyatta by addressing him in Luo language (an opposition ethnic group in Kenya) and declared Kenyatta’s own ethnic group, Kikuyus, a ‘threat’ to Tanzania’s national security.

As a regional power-broker, Museveni will need to sensitively manage evolving regional dynamics, not least with Sudan concerning the peace process in neighbouring South Sudan. Owing to competing interests, South Sudan’s civil war has largely been financed on the government’s side by Uganda and on the rebels’ side by Sudan. Museveni’s decision to host Sudan’s President, Omar al-Bashir – who is currently under an international arrest warrant from the ICC – at his inauguration ceremony, may contribute to ensuring a successful peace process which would facilitate more Ugandan exports to South Sudan.

A pivotal five years

Museveni’s next term may be pivotal for immediate and long-term stability in Uganda and East Africa. His plans for maintaining the status quo do not seem like a viable option in light of the various complexities and obstacles Uganda is up against politically and economically.

Uganda may be on a long-term downward trajectory toward instability. The electoral process showed that the country is divided and Museveni is facing a crisis of legitimacy. It is unlikely that a mixture of oppression and political patronage can resolve this. Nonetheless, these will likely remain the President’s preferred means of maintaining power.