Date: Fri, 20 May 2016 00:26:21 +0200

A QUICK GUIDE TO LIBYA’S MAIN PLAYERS

- Introduction

- Political actors

- Armed groups

- Jihadists

- May 19, 2016

Introduction

In Libya there are very few truly national actors. The vast majority are local players, some of whom are relevant at the national level while representing the interests of their region, or in most cases, their city. Many important actors, particularly outside of the largest cities, also have tribal allegiances.

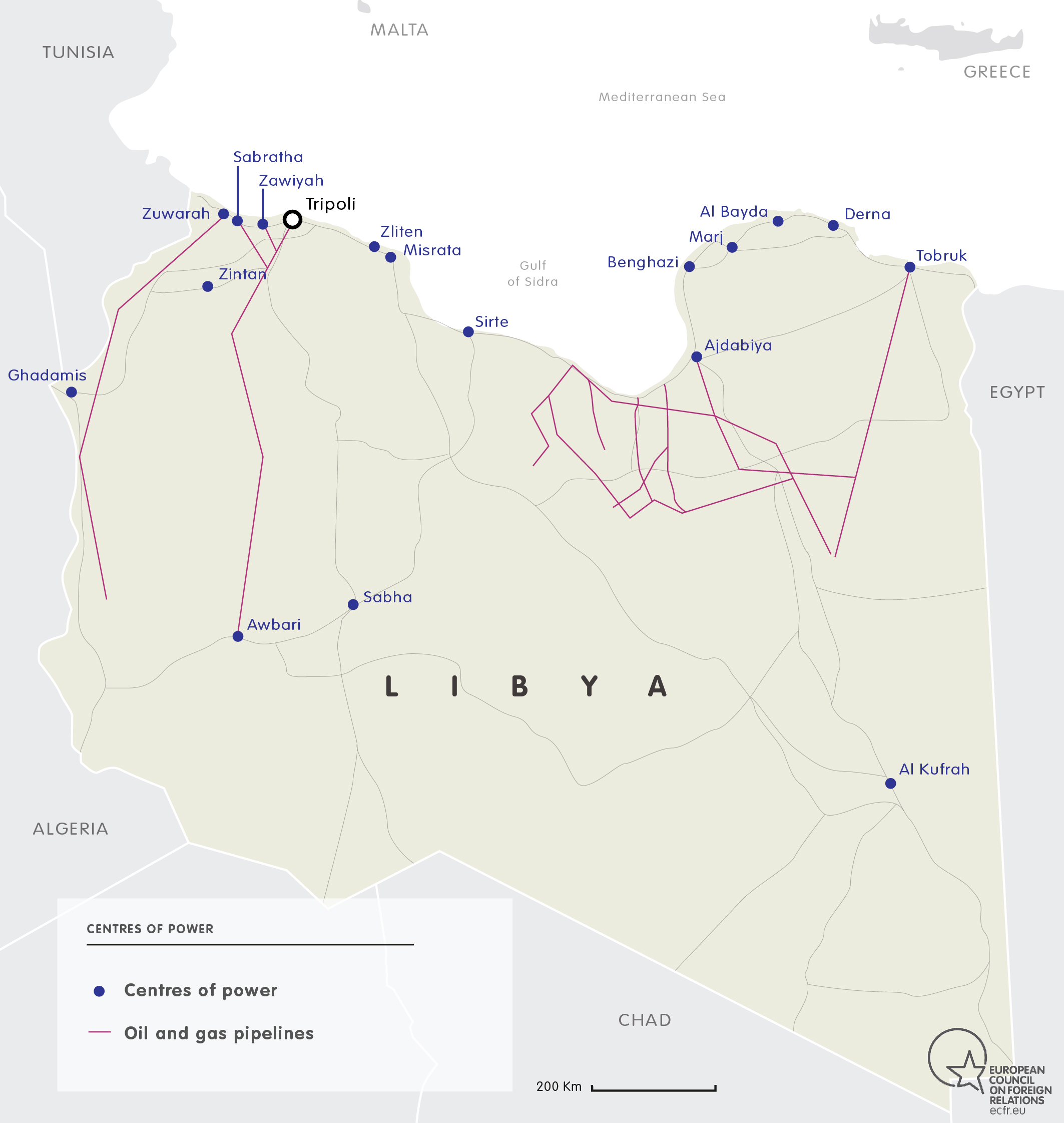

Since the summer of 2014, political power has been split between two rival governments in Tripoli and in Tobruk, with the latter having been recognised by the international community before the creation of the Presidential Council – the body that acts collectively as head of state and supreme commander of the armed forces - in December 2015. Several types of actors scramble for power in today’s Libya: armed groups; “city-states”, particularly in western and southern Libya; and tribes, which are particularly relevant in central and eastern Libya.

POLITICAL ACTORS

by Mattia Toaldo

One country, three governments

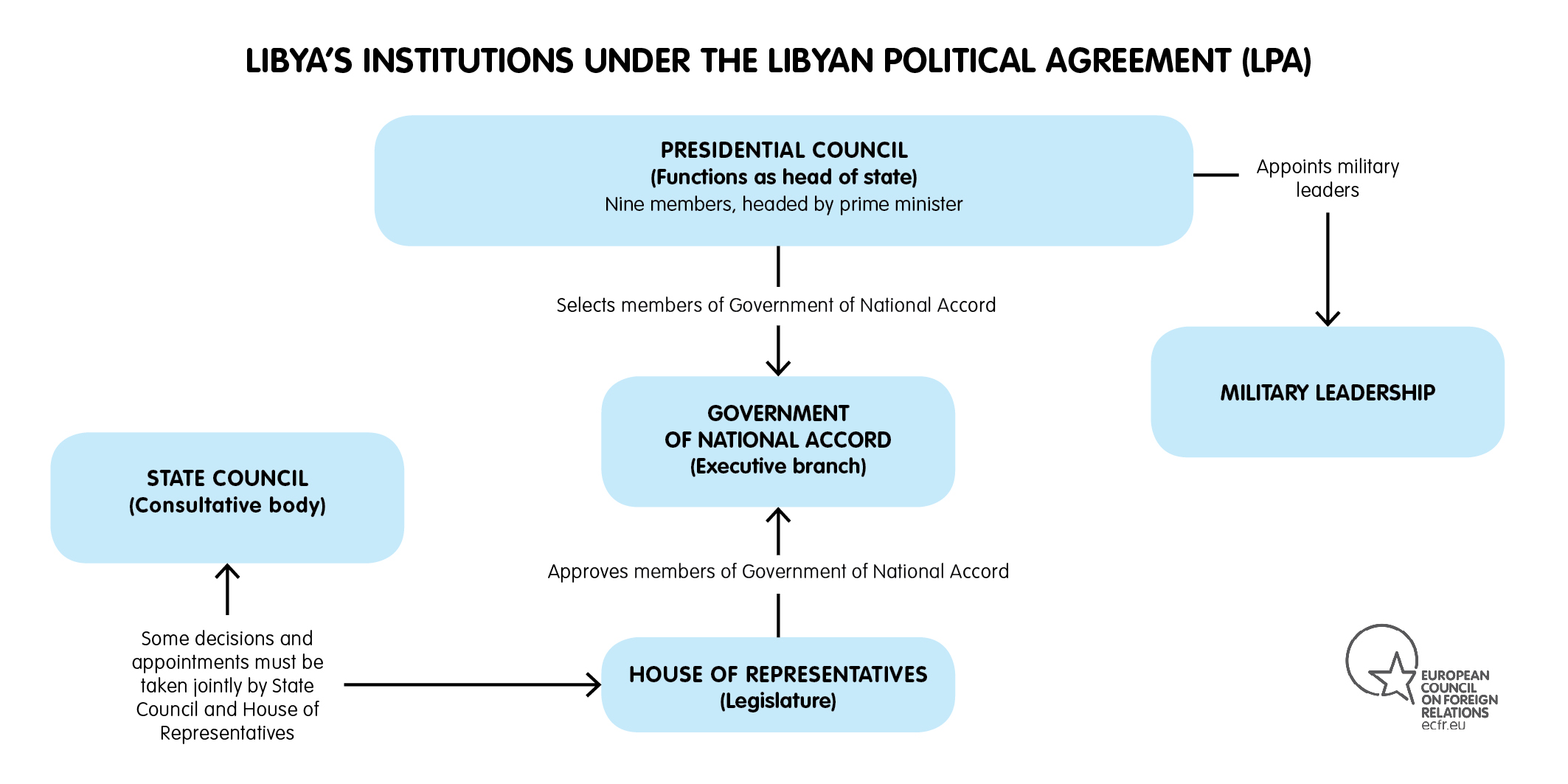

At the moment Libya has three centres of power. The first is the Presidential Council (PC), which has been located in the Abu Sittah navy base, a stone’s throw from central Tripoli, since 30 March 2016. The PC is headed by Fayez al-Sarraj – a former member of the Tobruk Parliament, where he represented a Tripoli constituency – and it was borne out of the signing of the UN-brokered Libyan Political Agreement (LPA) in December 2015. According to this agreement, the PC presides over the Government of National Accord (GNA), which is currently based in Tripoli. The GNA should be endorsed by the House of Representatives (HoR) which was previously based in Tobruk but could move elsewhere to guarantee the safety of its members some of whom have repeatedly reported being stopped from voting and threatened by members hostile to the GNA. For this reason, at the time of writing, the HoR has still not voted on the government, although on two occasions a majority of its members have expressed their support for it in a written statement.

The rival Government of National Salvation headed by Prime Minister Khalifa Ghwell - resting on the authority of the General National Congress (GNC), the resurrected parliament originally elected in 2012 - is also based in Tripoli, although it no longer controls any relevant institutions. The vast majority of the members of the GNC (also known as the “Tripoli Parliament”) have been moved across to the State Council, a consultative body created under the LPA which convenes in Tripoli.

The third centre of power is made up of the authorities based in Tobruk and al-Bayda, which also have to concede power to the GNA. The House of Representatives (HoR) in Tobruk is the legitimate legislative authority under the LPA, while the government of Abdullah al-Thinni operates from the eastern Libyan city of al-Bayda and should eventually concede power to the GNA once this is voted into office by Parliament. The Tobruk and al-Bayda authorities are under the control of Egyptian-aligned, self-described anti-Islamist general Khalifa Haftar, who leads the Libyan National Army (LNA). There is an ongoing movement among a large number of members of the HoR to change the location of the House to a more neutral place in Libya.

Prime Minister al-Sarraj and the Government of National Accord

Prime Minister al-Sarraj is not a strong figure on his own, but some of the other eight members that make up his Presidential Council have close links to powerful stakeholders.

His deputy Ahmed Maiteeq, who served a short stint as prime minister of Libya before being hit by a court ruling, represents the powerful city-state of Misrata, which is the biggest backer of the GNA from both a political and military standpoint. Misrata’s militias were a crucial component in the downfall of Gaddafi and are still one of the two most relevant military forces in the country.

Another important deputy is Ali Faraj al-Qatrani who represents General Haftar who in turn heads the LNA – the other large military force. Al-Qatrani is currently boycotting the meetings of the PC on the grounds that it is not inclusive enough.

Al-Qatrani is a close ally of another member of the Presidential Council, Omar Ahmed al-Aswad who represents the city-state of Zintan in western Libya. Zintan played a very important role in the fall of Gaddafi-controlled Tripoli in 2011 and has good relations today with the UAE.

A third deputy is Abdessalam Kajman who aligned with the Justice and Construction Party of which the Muslim Brotherhood is the largest component while Musa al-Kuni represents southern Libya.

Finally, Mohammed Ammari represents the pro-GNA faction within the GNC (the “Tripoli parliament”), and Fathi al-Majburi is an ally of the head of the Petroleum Facilities Guards (PFG) headed by Ibrahim Jadhran.

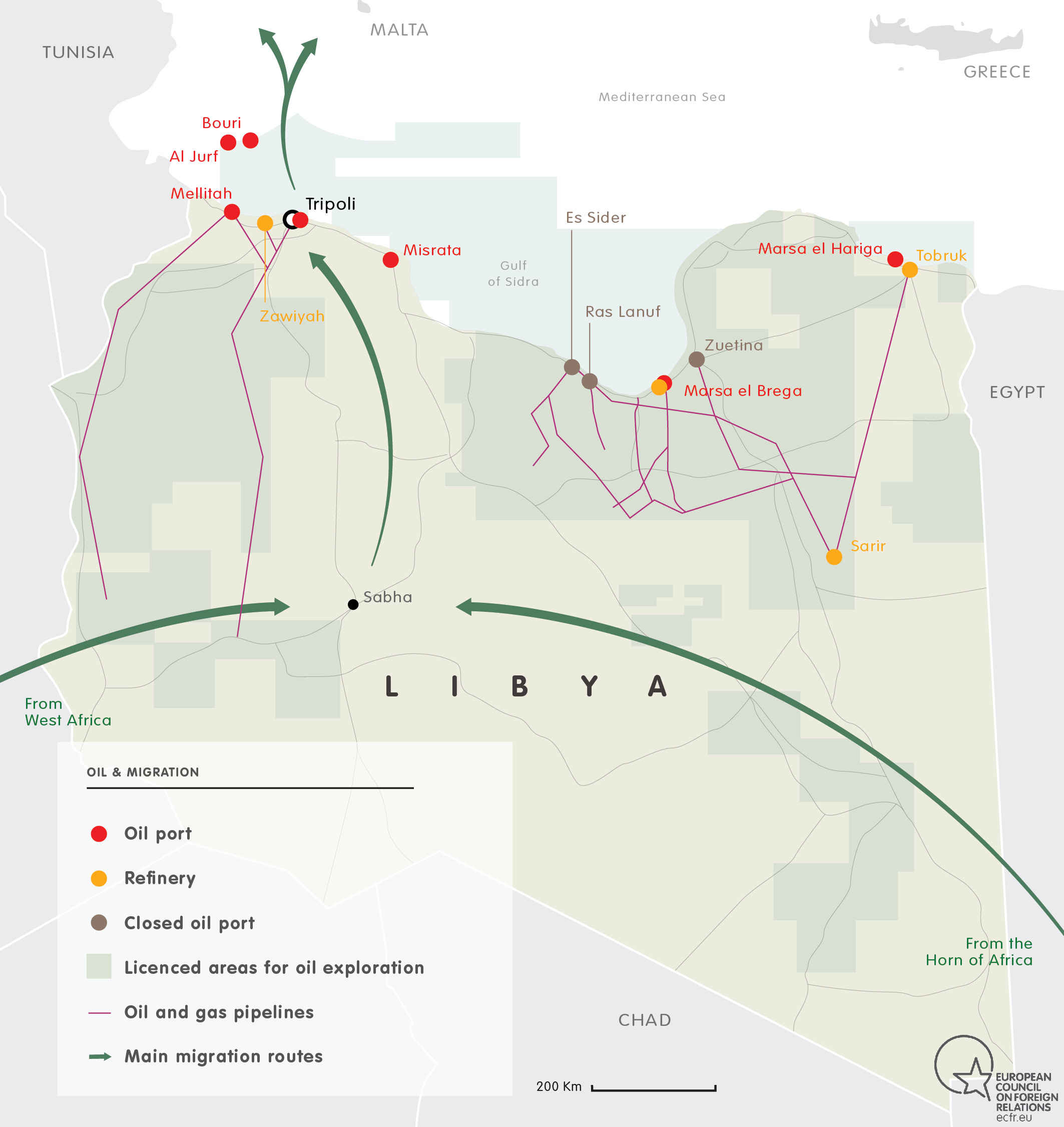

Two very important steps in consolidating al-Sarraj’s power base have been the pledge of loyalty by the two major Tripoli-based economic institutions (the Central Bank and the National Oil Corporation) and the statements of support by several municipalities in the West and South of the country.

In al-Sarraj’s government, two ministers stand out for the role they can play or have already played. Firstly, the Minister of the Interior Al-Aref al-Khuja has a police background and is in close contact with Tripoli’s militias. Secondly, the Minister of Defence Mahdi al-Barghathi, who is an army general from the same Libyan National Army of Haftar but politically distant enough from him to be accepted by other groups – and, in fact, rejected by Haftar himself.

Finally, within the power structure, a crucial role is played by the Temporary Security Committee (the TSC) which has conducted the security negotiations that allowed the PC to move peacefully to Tripoli on 30 March. Eventually, the TSC according to the LPA should be replaced by a proper National Security Council.

Abusahmain, Ghwell and the “Tripoli government”

The speaker of the General National Congress Nouri Abusahmain and the prime minister of the “Government of National Salvation” Khalifa Ghwell come from the cities of Zwara and Misrata respectively. Their military support base is the Steadfastness Front (Jabhat al-Samud) of Salah Badi. While they have received some weapons from Turkey in the past, they were never controlled or influenced by Ankara in the slightest. Initially they represented the Libya Dawn coalition which involves Islamists, the city-state of Misrata, and several other western cities (including parts of the Amazigh minority). Both Ghwell and Abusahmain have been hostile to the GNA and have been subjected to sanctions by the EU because of this. Their support base has gradually shrunk although they still retain some capacity to disrupt al-Sarraj’s activities here and there, particularly if popular support for him decreases or if some of the militias now supporting him decide to switch sides.

Haftar, Aguila Saleh, and the Tobruk power centre

The link between the head of the armed forces Khalifa Haftar and the Speaker of the Tobruk parliament Aguila Saleh Issa is very strong. Haftar rules from his headquarters in Marj (in eastern Libya) and has strong military control over both the al-Bayda government and the HoR in Tobruk. Also because of Haftar’s popular support in eastern Libya, very little happens in the HoR without his approval. Recently, Haftar’s forces made significant advances in Benghazi both against the Islamic State group (ISIS) and against the Islamist-dominated Benghazi Revolutionary Shura Council.

The Petroleum Facilities Guards and Ibrahim Jadhran

While al-Sarraj’s support base is now concentrated mostly in the West and in the South of the country, his more powerful ally in the East is Ibrahim Jadhran, the head of the PFG. A controversial figure, Jadhran fought against the militias from the city of Misrata in the past and is criticised by many Libyans for instigating and upholding a blockade of oil fields between 2013 and 2014. He now supports the PC, mostly because of a personal disagreement with general Haftar that erupted early in 2015. It is unclear whether all of the PFG stands behind Jadhran.

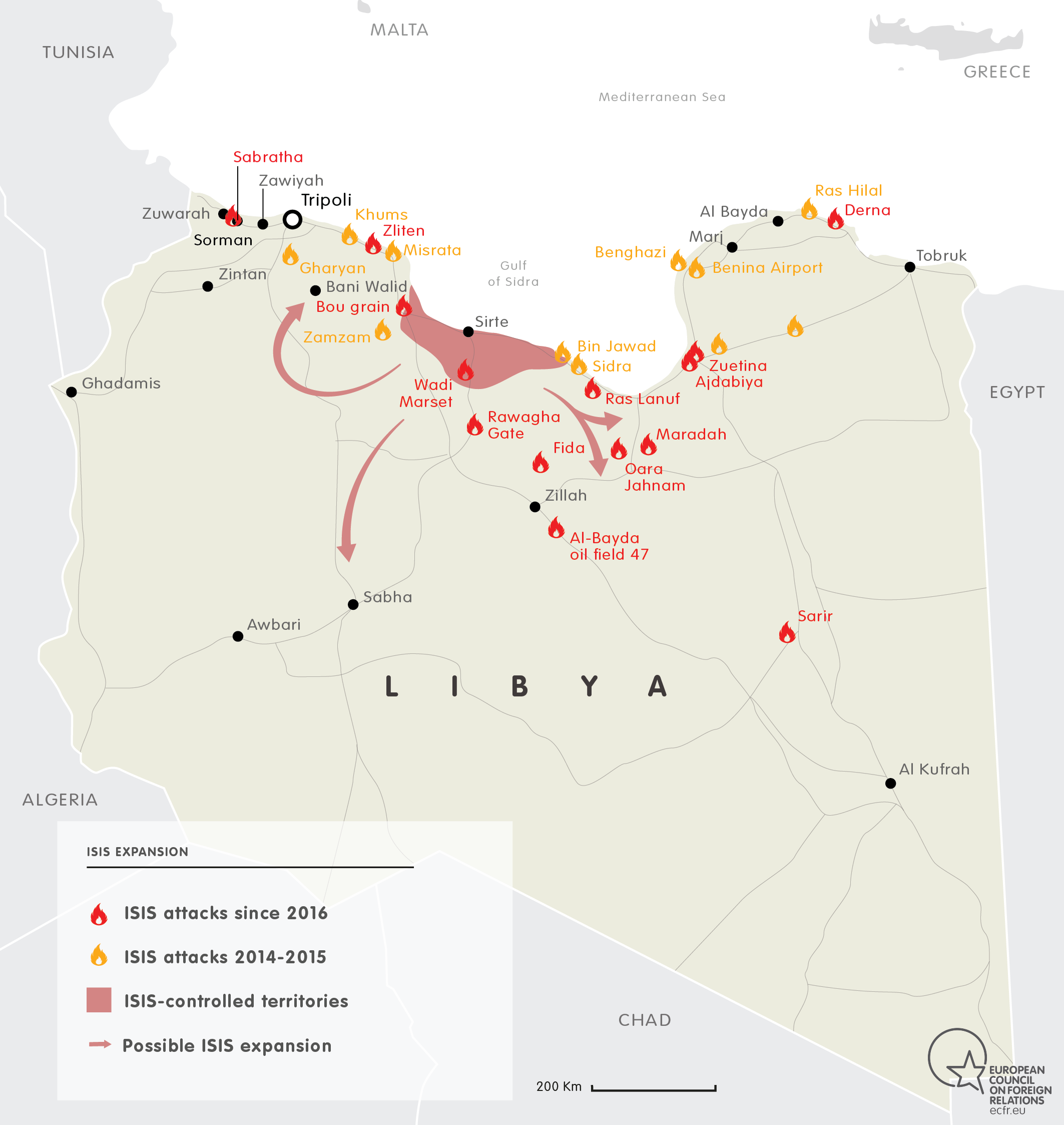

The Islamic State group in Libya

Also called Tandhim ad-Dawla (the Organisation of the State) by Libyans, ISIS now controls the central Mediterranean coast of Libya around the city of Sirte. It has carried out attacks in all major Libyan cities, including the capital Tripoli. ISIS also has a presence in other parts of Libya, such as Derna, Benghazi and Sabratha, although it has suffered significant setbacks in all three cities since the beginning of the year.

Regional actors

Egypt

No other Arab country plays as powerful a role in Libya as Egypt. Testament to Egypt’s involvement in the region is the regular travel Libyan leaders make to Cairo. The relationship between Tobruk and Egypt is not just defined by significant arms deliveries but also by a shared political project: eradicating political Islam and enhancing the autonomy of eastern Libya. For Egypt, according to some authors, having Cyrenaica – the eastern region of Libya – under the role of a leader that is friendly to Egypt – Haftar for instance – would create a buffer zone with ISIS and a territorial hinterland for any opposition to the regime in Cairo.

Nevertheless, over time Egypt has put out at least two statements that contradict this position. On the one hand, diplomats and the MFA have given assurances of their support to the UN-led political process; on the other, the security apparatus has supported Haftar even when it was clear that he was on a collision course with UN-backed unity efforts.

United Arab Emirates

Although sharing some of the same goals as Egypt, the UAE has a more nuanced position on the situation in Libya. Reportedly, it has been more supportive of UN negotiations and ultimately less engaged on Libya since its intervention in Yemen. Nevertheless, Emirati weapons are still delivered to both Haftar and the militias of the city-state of Zintan, according to a report from a UN panel of experts. Moreover, the UAE’s political influence should not be underestimated. The Libyan ambassador to Abu Dhabi, Aref al-Nayed, is ideologically one of the most important figures on the Tobruk side. He was even touted as potential prime minister at one point.

Turkey and Qatar

Neither Turkey nor Qatar have the same level influence on the Government of National Salvation that Egypt and the UAE have on the Tobruk side, although they would like to think they do. Turkish companies have, according to the UN panel of experts, delivered weapons to one side (the defunct Libya Dawn coalition) and Qatar has links with one Libyan politician and former jihadist – Abdelhakim Belhadj. Yet none of the major Libyan actors respond to input from Ankara or Doha the way that Tobruk aligns itself with Cairo’s policies.

Armed groups

by Mary Fitzgerald

The terms “army” and “militia” mean different things to different Libyans and this is one of the consequences of the political power struggle that has roiled Libya since 2014.

Haftar and the Libyan National Army

While Khalifa Haftar is recognised as general commander of the armed forces by the HoR in eastern Libya, his self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA) is a mix of military units and tribal or regional-based armed groups, and is not recognised as a proper army by all military personnel across the East or West of Libya. A number of senior military figures refused to join Haftar’s Operation Dignity against Islamists when it launched in May 2014. Some of these have since joined forces with his adversaries, whether cooperating with militias that comprised the Libya Dawn coalition in western Libya, or joining with local jihadist-led groups to drive ISIS out from the eastern town of Derna.

The former Libya Dawn

The Libya Dawn militia alliance that formed partly in response to Haftar’s Operation Dignity in summer 2014, and which drove then Dignity-allied militias from the western town of Zintan from Tripoli, no longer exists. The coalition was made up of both Islamist and non-Islamist militias, armed groups from Tripoli and the port city of Misrata, and fighters from other parts of western Libya, including from the Amazigh minority. It had fractured even before the UN-brokered deal aimed at establishing a unity government was signed late last year.

Tripoli

At present, Tripoli’s armed groups can be broadly categorised in terms of whether or not they support the unity government led by Fayez al-Sarraj that is currently trying to find its feet in the capital. For now, a majority are either explicitly supportive of, or ambivalent towards, the unity government. Those in the latter category are waiting to see if their interests will be maintained under the new dispensation. One of the most important figures supporting the new government is AbdelRauf Kara, leader of the Special Deterrent Force (or Rada) which is based in the Maitiga complex, also home to Tripoli’s only operating airport. Kara’s Salafist-leaning forces – which number around 1,500 – once sought to present themselves as a type of police force for the city, targeting alcohol and drug sellers in particular. Now they focus their efforts on tackling ISIS cells and sympathisers in the capital. Kara’s men are currently forming a counter-terrorism unit with members of army special forces in western Libya who refused to join Haftar. Armed groups from the Suq al-Jumaa area of Tripoli, including the Nawasi brigade, are also key to securing the unity government.

Another powerful figure in Tripoli is Haitham Tajouri, who heads the city’s largest militia. Tajouri, whose forces have threatened and intimidated officials since 2012, is not a particularly political figure. His priority is protecting the considerable interests he has accrued in the capital, and for now he remains ambivalent about the unity government.

Tripoli’s Islamist-leaning militias, some of which have links to figures from the now defunct Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG), tend to be the most sceptical of the unity government, though none have yet translated their scepticism into armed action.

Misrata

The prosperous port city of Misrata is home to Libya’s largest and most powerful militias. Misrata is not as cohesive as its residents sometimes claim. Local rivalries feed the power-play between the city’s constellation of armed groups. Prominent political and business figures in Misrata support the unity government, which includes the prominent Misratan, Ahmed Maiteeq, as deputy prime minister. This has helped secure the backing of the main armed groups from the city, including the two biggest – the Halbous and the Mahjoub brigades. A wildcard in Misrata is Salah Badi, a controversial former parliamentarian and militia leader who was a key figure in the Libya Dawn alliance in 2014 and who opposes the UN-backed unity government. Misratan forces have attempted a containment strategy to prevent ISIS from expanding westwards from its stronghold of Sirte, but they lack the capacity to eliminate ISIS entirely from the city.

Zintan and the Tribal Army

The small mountain town of Zintan enjoyed outsized influence in western Libya from 2011 until summer 2014 when its militias were driven from Tripoli by Libya Dawn. As a result, Zintani forces lost control of key strategic sites, including Tripoli’s international airport which was destroyed in the fighting. Some later joined with the so-called Tribal Army – comprising fighters from the Warshefana region on Tripoli’s hinterland and other tribal elements from western Libya – to confront Libya Dawn-allied factions. Fighting later subsided due to local ceasefires. A number of Zintani forces have distanced themselves from Haftar, while others remain supportive. Zintan’s militias, in light of the losses they suffered in 2014, are also assessing how they might fit into the changing order.

Benghazi: Haftar, the Benghazi Revolutionary Shura Council and ISIS

Fighting continues in Benghazi between the forces that joined Haftar’s Operation Dignity and their opponents, though the latter have been squeezed into a handful of districts after a major Dignity push in February resulted in several neighbourhoods being captured. Key to the anti-Dignity camp is the Benghazi Revolutionary Shura Council (BRSC), an umbrella group comprising a number of Islamist and self-described revolutionary factions. It also includes the UN-designated Ansar al-Sharia. The BRSC fights alongside ISIS against Haftar’s forces. The BRSC’s ranks have been fed by youth radicalised by Haftar’s campaign, which sought not only to eradicate Islamists of all stripes, including the Muslim Brotherhood, but also took on an ethnic character at times, targeting families of western Libyan origin in the city.

Both the Dignity and anti-Dignity camps in Benghazi have experienced internal rifts. Within the Dignity camp, which comprises army units, militias and armed civilians, the most important actor is the military special forces unit, known as Saiqa. The Saiqa is led by Wanis Bukhamada, a popular figure in the city. Some Dignity commanders in Benghazi have been critical of Haftar’s leadership, including Mahdi al-Barghathi, the designated defence minister of the unity government. Also of concern to many residents are the hardline Salafist fighters that joined Haftar’s coalition in 2014 and have been empowered as a result, taking over mosques and other institutions. Similarly, within the BRSC, tensions have grown over its relationship with ISIS, and some of its backers have pushed for the BRSC to distance itself from the group.

The Petroleum Facilities Guards

Once present in several regions of Libya, the PFG has fallen apart and the term is now mostly used to refer to the forces in eastern Libya under the command of Ibrahim Jathran, a former revolutionary fighter. In 2013 his PFG took control of the main oil export terminals in eastern Libya and later attempted to sell oil. The almost year-long episode cost Libya billions in lost revenues. While Jathran is often referred to as a federalist, he is not universally popular within the wider movement seeking regional autonomy for eastern Libya, and he can be better described as a political pragmatist, if not an opportunist. He has alternately allied himself with both the HoR and its opponents in western Libya. While Jathran initially claimed to be supportive of Haftar’s Dignity campaign, his relationship with Haftar has since soured to the extent he has accused Haftar’s forces of trying to assassinate him. The PFG has repelled several ISIS attacks on oil infrastructure in eastern Libya and Jathran currently supports the UN-backed unity government. There are claims of dissent within the existing PFG, and rumours that Jathran no longer controls the entire eastern PFG, although the extent of this dissent is unclear.

Jihadists

by Mary Fitzgerald

Libya is home to a range of jihadist groups, from the Islamic State group (ISIS) to al Qaeda-linked groups, to other Salafi-jihadi factions. Some are wholly indigenous and rooted in particular locales while others – particularly ISIS affiliates – have many foreigners at both leadership and rank and file level.

The legacy of LIFG

Libya’s jihadist network can be divided along generational lines, starting with those who emerged in the 1980s. Many from that older generation fought against Soviet-backed forces in Afghanistan. These veterans later created a number of groups in opposition to Muammar Gaddafi, the largest of which was the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) which is now defunct. Several former LIFG figures, including its final leader, Abdelhakim Belhadj, played key roles in the 2011 uprising and went on to participate in the country’s democratic transition, forming political parties, running in elections and serving as deputy ministers in government. This did not sit well with the second and third generation of jihadists - among the former were those who fought in Iraq after 2003, among the latter were those who fought in Syria after 2011 – who lean towards more radical ideologies and reject democracy as un-Islamic. The Libyans that have joined ISIS in the country tend to come from the second and third generations.

ISIS in Libya

Local returnees from Syria helped form Libya’s first ISIS affiliate in the eastern town of Derna in 2014. Many had fought as part of ISIS’s al-Battar unit in northern Syria before returning home to replicate the model with help from senior non-Libyan ISIS figures. The leadership of ISIS in Libya has always been dominated by foreigners, and the group’s current leader is Abd al-Qadir al-Najdi, whose name suggests Saudi origins. He replaced an Iraqi whom the US claims it killed in an airstrike in eastern Libya last year.

ISIS leader Abu Bakr al Baghdadi recognised the presence of ISIS in Libya in late 2014, declaring three wilayats or provinces: Barqa (eastern Libya), with Derna as its headquarters; Tarablus (Tripoli), with Sirte as its headquarters; and Fezzan (southwestern Libya).

ISIS was driven from its first headquarters in Derna last year by a coalition of forces which included the Derna Mujahideen Shura Council, an umbrella group comprising fighters led by local jihadists including LIFG veterans, who joined with army personnel who had rejected Khalifa Haftar and his Operation Dignity campaign. More recently, the same alliance routed ISIS from its remaining redoubts on the outskirts of the town.

ISIS began to build its presence in Sirte in 2011. Sirte, which was Gaddafi’s former hometown and one of the regime's last hold-outs during the 2011 uprising, is now an ISIS stronghold. Prominent ISIS cleric Turki al-Binali and other senior figures visited Sirte as the group began to consolidate control. It did so by reaching out to locals who felt aggrieved over the city’s marginalisation in post-Gaddafi Libya. However, the group met some resistance in summer 2015 as a number of residents attempted an uprising, which was then brutally quashed. Since then ISIS has tried to impose a system of governance on the city, using public executions to instil fear. It has also sought to expand its sphere of influence throughout the surrounding region, taking control of a series of small towns east of Sirte from which it has mounted attacks on nearby oil infrastructure. However, as its leader al-Najdi admitted in a recent interview with an ISIS publication, Libya’s array of armed groups and the rivalries between them has so far made it difficult for ISIS to expand much beyond Sirte’s hinterland.

ISIS also had a smaller presence on the outskirts of Sabratha, a coastal town in western Libya, until a combination of US airstrikes and attacks by local forces - including former jihadists from that first generation - managed to uproot the militants earlier this year. In Benghazi, those fighting Haftar’s Operation Dignity include Libyan and foreign members of ISIS. Although Sirte is the group’s ostensible base, ISIS sleeper cells operate in Tripoli and other cities and towns in Libya. While the Pentagon estimates there are over 6,000 ISIS fighters in Libya, the UN and many Libyans believe that the number is lower.

Ansar al-Sharia in Libya

Formed in 2012 by former revolutionary fighters calling for the immediate imposition of sharia law, Ansar al-Sharia’s first branch was set up in Benghazi, but affiliates have also emerged in towns such as Derna, Sirte and Ajdabiya. While Ansar al-Sharia’s leadership tended to be drawn from Libya’s second generation of jihadists, the majority of its rank and file were from the generation that came after it. The UN put Ansar al-Sharia on its al-Qaeda sanctions list in 2014, describing it as a group associated with Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and Al-Mourabitoun. Both groups mentioned also have a presence in Libya, both in the south and central/eastern regions, largely through Libyans who once worked with them elsewhere, particularly in Algeria, before returning home after Gaddafi was ousted.

Ansar al-Sharia has run training camps for foreign fighters, including a significant number of Tunisians, travelling to Syria, Iraq and Mali. Individuals associated with Ansar al-Sharia participated in the September 2012 attacks on the US diplomatic mission in Benghazi.

While they are, at the core, an armed group, Ansar al-Sharia adopted a strategy between 2012 and 2014 that focused on preaching and charitable work to build popular support and drive recruitment. As a result, it became the largest jihadist organisation in Libya, with its main branch being stationed in Benghazi.

In response to Khalifa Haftar’s Operation Dignity, Ansar al-Sharia’s Benghazi unit merged with other militias to form the Benghazi Revolutionary Shura Council (BRSC) in summer 2014. While Ansar al-Sharia is now the dominant force in the BRSC coalition, it has experienced internal disarray due to the deaths of senior figures - including founder Mohammed Zahawi – and the loss of a number of members through defection to ISIS. Other Ansar al-Sharia units across the country also experienced an uptick in defections as ISIS began to expand in Libya. With ISIS trying to further co-opt existing networks, tensions have grown between it and Ansar al-Sharia (and by extension with the latter’s associates in AQIM and Al-Mourabitoun) as they compete for members and territory. However, in Benghazi they still fight together against Haftar’s forces. The rivalry between ISIS and al-Qaeda associated groups like Ansar al-Sharia is likely to define Libya’s jihadist milieu for the forseeable future.

Intervening better: Europe’s second chance in Libya

The publication draws on extensive work in the region and interviews with Libyan officials to explain how the West can do a better job of intervening in the country after the failure of the post-Gaddafi transition.

It argues that Libya is at a dangerous turning point. The unity government is facing two rival governments and dozens of armed groups. Once one of Africa’s wealthiest nations, Libya is in desperate need of humanitarian aid, and its chaos threatens to unleash greater migration flows and terrorism on Europe.