Only Africa has solutions to African problems. That requires a healing leadership. We need to mobilize the people to reform the current leadership mindset, which is only destructive. Africa needs to address issues of civic education, of citizens being able to elect leaders who will make a difference, and to ensure we have institutions that make it impossible for anybody to act as if there were no laws.

Diagnosis: Negative leadership

In the 1960s, most African countries snatched their independence from the colonialists, but often without a broad and unifying vision to reconcile the leadership with the emancipatory aspirations of the people. In this context, without considering the specificity of the continent’s history, the victory of emancipation was short-lived or aborted. The new government systems in place could not satisfy the peoples’ aspiration for dignity, or gain the ability to pilot entire nations to achieve true liberty. Post-colonial Africa has gone through extreme odds. Since the 1960s, roughly 40 wars have resulted in 10 million deaths and created more than 10 million refugees.

Independence became nothing more than the perpetuation of colonialism as the new states’ leadership could only prevail under the approval of former colonial powers. Most of the time, to become a leader in Africa, you must be loved or accepted by Washington, Paris or London. The leadership did not attend to the needs of the population but instead worked hard to please the former colonial and imperialist powers. The countries ran as if they were still colonies. The legitimacy of today’s African leaders is put to question because it is difficult to work with a clear conscience for the realization of a vision imposed by others. In addition, the use of arbitrary violence to impose an alien vision on the people only aggravates the illegitimacy. Moreover, where there is domination, resistance is bound to emerge.

Political instability in Africa is endemic, cycling to endless violent crisis. It is a consequence of the violent creation of African states by colonial conquests; creation that was sanctioned by the International Berlin Conference of 1884-1885. Africa is a product of 500 years of struggle against a system that remains updated, sophisticated and globalized. It is a product of setbacks endured from the slave trade, the colonial conquests, resource plundering, wars, dictatorial regimes, and neo-colonialism brought by contradistinctions of the Cold War era.

The forms of structural adjustment imposed on the overall society by external forces have given birth to a culture of violence. As Jean de La Fontaine in Fables says: “The motive of the strongest is always the best. (Might is always right.)”. Hence an entrenched tradition of corruption and clientelism. It is clear that foreign interventionist forces push African governments to kneel to external powers even more than before their own people, whom they are supposed to serve. If one looks at history, one gets the feeling that instability has always been caused by the difficulty of articulating national interests within the interests of exogenous powers. Africa’s leadership crisis is manifested by trends of corruption, persistent abuse of power, lack of respect for the Constitution, and failure to create an environment where the young generation can have the possibility to nurture with true competence, to make a commitment to social justice and to develop the necessary skills for peace building.

While some first-rate political leaders spearheaded the struggle for independence, the nation-building process has not only failed to produce leaders of comparable stature, but it has also witnessed a decline in its achievements – aggravated by unethical leadership and bad governance (Adamoleku 1988:95). This frustrates the legitimacy of the leadership and their power by creating a toxic leadership and oppressive institutions.

In his first official trip in July 2009 to sub-Saharan Africa, addressing the Ghanaian assembly in Accra, President Obama declared, “Africa doesn't need strongmen, it needs strong institutions”. It is only through positive leadership that Africa can create strong institutions. A wicked leader is the one whom the people despise and the good leader is the one the people revere. The great leader is the one about who the people would say: “We did it ourselves.” (Lao Tzu). Like in the Bible (Matthew 20: 25:27), Jesus says to his disciples: “….You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their high officials exercise authority over them. Not so with you. Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first must be your slave.”

The example of Jesus’s teaching emphasizes a leadership that serves others (servant leadership). Jesus submitted his own life to sacrificial service under the will of God (Luke 22:42), and he sacrificed his life freely out of service for others (John 10:30). He came to serve (Matthew 20:28) although he was God’s Son and was thus more powerful than any other leader in the world. He healed the sick (Mark 7:31-37), drove out demons (Mark 5:1-20), was recognized as Teacher and Lord (John 13:13), and had power over the wind and the sea and even over death (Mark 4:35-41; Matthew 9:18-26). In John 13:1-17 Jesus gives a very practical example of what it means to serve others. He washes the feet of his followers, which was properly the responsibility of the house-servant.

During the long Cold War, strong states with one-party regimes as an expression of power held sway. However, with the advent of democracy in the 1990s, freedom created by liberal economies brought back the concept of leadership in Africa as a key element of sound management of public affairs. Yet the issue of leadership is still unclear in African mentality due to the legacy of colonialism. This poses the question of the future of post-colonial states, because of recurring socio-political crises and the difficulties of allowing the population to own the leadership. The need to invent a new mode of governance that would not compromise the democratic process became evident starting in the 1990s.

In Africa, during elections, the masses choose the candidate, not based on the issues raised or virtue, but based on subjective considerations such as tribal, regional affiliations or material gain. A new concept of leaderships is needed to bring about peace and healing where it has been violently removed for centuries. This is already seen through the repeated rigging of elections and the gradual return of the military to power.

Our continent has suffered from a lack of leadership able to have a vision that would uplift the population and affirm their strategic position in the globalized world. There should be a leadership that inspires a certain sense of pride and dignity for the people whose conscience is still marked by major traumas. The submissive tendencies and docility that still dominate African minds tend to maintain the continent on the path of incompetency and mediocre performance. This predicament, which dates back to the era of the slave trade, through the colonial period to the successive dictatorships, cannot easily turn a population of over a billion people into peaceful nations.

The excessive concentration of power in the hands of a few is one aspect that has stifled free local initiatives. Gradually but surely, institutions have been emptied of their national and patriotic content, and this has resulted in the ruin of several countries on the continent. The deterioration of the states favored a bureaucratic system, which systematically impoverished a large majority of the population. Because basic human needs, rights and fundamental freedoms are not met, this can only be a foundation for structural and direct violence. Structural violence causes direct violence and direct violence reinforces structural violence; both are interdependent of each other. Structural violence is the cause of premature deaths and avoidable disability that effects people closely linked with social injustice. It is not a coincidence that, “in several sub-Saharan countries, a person can hope to live on average only 46 years, or 32 years less than the average life expectancy in countries of advanced human development, with 20 years slashed off life expectancy due to HIV/AIDS,” according to the UNDP.

As the crisis of ethical political leadership is responsible for Africa’s underdevelopment and insecurity, and its social and structural injustices, we need to rethink the kind of leadership that is needed. The future leadership must focus on serving African populations by taking care of their well being through developing the health, education, economic, security and other critical sectors. The population must be the driving force of this development. The leadership crisis will be transformed if the economy empowers the vulnerable. Economic growth and expansion of the middle class is fundamental for the ‘emergence of a vibrant civil society which in turn places ever greater pressure on the state to establish more participatory forms of governance…’ (Paczynska 2008:238).

In developed nations where the majority of the population are economically stable, civil war is unlikely. Meeting citizens’ human needs is a long-term solution to the leadership crisis. Poverty reduction, employment provision, and economic security ameliorate not only the leadership crisis, but also insecurity (Jeong 2000; Paczynska 2008). Leaders from the public and private sectors and faith communities will consider best practices and proven models that advance social and political stability. We need a leadership that will transform African economies by eliminating war, conquest, looting, and predation to economies of peace, which first serve the needs of the population.

Given the history of war, violence, political and ethnic hatred in Africa, leadership transformation requires a capacity for forgiveness and non-violence from leaders and citizens for peace to flourish.

Healing leadership: the way to peace

Over the past three decades efforts have been made to resolve conflicts in Angola, Burundi, Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ivory Coast, Kenya, Liberia, Mozambique, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, Uganda, etc. The success or failure of the dialogue process is always the determining point that shows whether the countries will remain at war or engage toward the road to peace.

In 1992, the Arusha (Tanzania) Agreement collapsed, paving the way to the 1994 Rwandan genocide. A decade later, the Naivasha Agreement signed in Kenya (2005) ended one of the longest civilian wars between South and North Sudan. This led to a referendum in 2009, which won the independence of South Sudan. But independence did not end conflict in South Sudan. The ongoing civil war since 2103, just two years after independence, has displaced some 2.2 million people and threatened the success of the world's newest country.

When the root cause of the conflict is not well-addressed we have a negative peace, which addresses only needs of those who threaten peace (both rebel and government leaders), and so the victims are not heard. Negative peace refers to the absence of violence (Johan Galtung, 1996). When, for example, a ceasefire is enacted, a negative peace will ensue: violence stops, guns are silenced but still the war is not yet ended. Positive peace is filled with positive content such as restoration of relationships, the creation of social systems that serve the needs of the whole population and the constructive resolution of conflict (war ended). Therefore, peace is not the absence of conflicts but the absence of violence in all forms (direct or structural violence) and the establishment of creative ways to resolve conflict (healing leadership).

In Kenya, paradoxically, the mediation by Kofi Annan in 2008 prevented a shift in the continuation of violence. In other cases, like in D.R. Congo, after several peace agreements were signed since 2000, the results have been a mixture of success and failure. Both war and peace coexist and prevail in different parts of the country. The regular change of actors involved in the conflicts changes the nature of the conflict itself.

Underlying unsolved conflicts are the root causes of violence, caused by incompatible and contradictory goals; so that pursuit of one’s goal blocks someone else’s goals (clashing goals). Consequently, underlying conflicts as a cause must be identified and solved by making goals compatible in a sustainable way and acceptable to all parties concerned (mediation). When mediation is successful, the peace agreement content can positively affect future outcomes for the country in terms of social life, security and power balance.

However, today another popular concept of peace is imposed on Africa; it is a kind of peace that responds to the demands of those directly involved in the violence (both political and rebel leaders) instead of the demands of the victims. In that way, violent conflict naturally becomes endemic, raising questions on the volatile nature of the peace concluded after these multiple negotiations, mediations and peace agreements. The peace process should be built from the ground up (endogenous); the victims or the affected should be the starting point in terms of what kind of peaceful society is needed. The population needs to be empowered by creating specific institutions that will make them realize how important it is to protect their interest, and when it comes to selecting leaders, how important it is to change them if they're not doing what the community wants. Therefore, the national government should not act from commands from outside more than from the needs of the population inside.

That is why we need to transcend toward a healing inspired leadership. Even for the whole world, poor leadership within the global institutions may create disaster internationally, bringing the possibility of nuclear war or a nuclear accident that can destroy humanity, or a global recession, famine, or even an epidemic. It is therefore clear that the question of leadership is crucial. A healing leadership creates a framework through which it helps people to understand and confront the problem, however painful it may be, and finds solutions together after having examined all possibilities. It creates a culture of “we win together” (solidarity) instead of “we win against the other”.

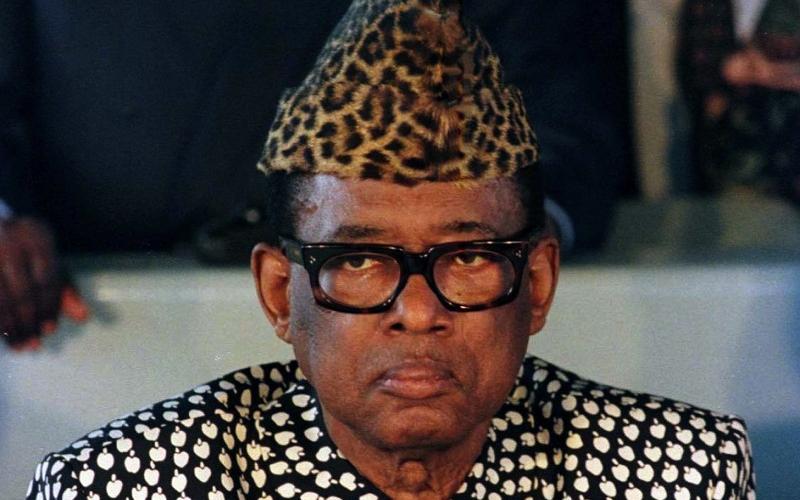

On the other hand, negative leadership will tend to present itself as the only key to problem solving. Remember the strong charisma of the likes of late dictator Mobutu of the Zaire, who said once: “Après moi, c est le deluge” meaning “After me, the deluge”? ("The world could collapse after I'm gone, no big deal"). It was an expression attributed to Louis XV, or the phrase may have been coined not by the king himself, but by his most famous lover, Madame de Pompadour (1721-1764). This kind of negative leadership, when removed, will leave a serious sequel for society; it is a kind of leadership that demands destruction, removal and silencing of other opinions before rendering services. This is too familiar in Africa.

To bring about healing leadership, we will need to mobilize the people locally to take responsibility to change the current leadership mindset, which is only destructive for society. Africa needs to address issues of civic education, issues of being able to elect people who are going to make a difference, and to make sure we have the institutions that make it impossible for anybody to function as if there were no laws.

Conclusion

Africans’ aspiration to control their destiny is growing. In 1998, when the UN released its first major report on the "causes of conflict" in Africa, 14 countries were at war. This report was based on consultations between African states, civil society groups, academics, and various departments and United Nations agencies. The main message of the 1998 report remains true today: "Only Africa can find solutions to African problems".

Today there is a decline in violence, but most of the countries are still affected by the impact of armed conflict; they are politically fragile and institutions are weak. The economies are in jeopardy, producing a high rate of unemployment among the youth. A multitude of new challenges arises, ranging from climate change to cross-border crimes. These problems, if left unresolved, can revive old conflicts or provoke new crises.

At the African Union Summit in 2010, African leaders proclaimed 2010 as a “Year of Peace and Security”. According to Jean Ping, the then Chairperson of the AU Commission, the leaders expressed their determination "to put an end to the scourge of conflicts and violence on the continent. Today's leaders must not bequeath the burden of violent conflicts to the future generations ".

Africa can claim tremendous progress toward peace in the last decade but also various enlightening initiatives such as the establishment of AU (African Union) in 2002 to replace the defunct and ineffective Organization of African Unity (OAU). The AU has set up several institutions and mechanisms to prevent and manage conflicts, including the Peace and Security Council that has implemented a series of peacekeeping operations: the African Union Mission in Sudan (AMIS) in 2004 for the Darfur conflict, African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) in 2007; the African-led International Support Mission to the Central African Republic (MISCA) in 2013, and the Eastern Africa Standby Force (EASF) in 2002. Currently, the UN provides logistical support to 6,200 AU troops in Somalia and is working alongside the organization in a joint operation in the Darfur region in western Sudan.

To many observers, to make these initiatives successful, they must not be imposed from outside. But they should be taken over and run by the communities involved and enjoy the full participation of local institutions and organizations, in particular civil society, women, youth and children.

To avoid renewed violence in post-conflict countries - and to prevent the outbreak of new conflicts elsewhere on the continent - the leadership capacity need to improve. For Africa to address the many problems that cause conflicts - such as widespread corruption, economic inequality and exclusion of certain ethnic and social groups - it is essential to have democratic, well-governed states. To achieve peace and stability, Africa must reform its current leadership by putting emphasis on the demilitarization of minds and political institutions.

* Rais Neza Boneza is an author of fiction as well as non-fiction, poetry books and articles. He was born in the Katanga Province of the Democratic Republic of Congo. He is also an activist and peace practitioner. He is co-convener of TRANSCEND Global Network; a peace development environment network. He also uses his work to promote artistic expressions as a means to deal with conflicts and maintaining mental well-being, spiritual growth and healing. Boneza has travelled extensively in Africa and around the world as a lecturer, educator and consultant for various NGOs and institutions. His work is premised on Art, healing, solidarity, peace, conflict transformation and human dignity.

Sources

De Witte, Ludo, 2000, L’assassinat de Lumumba. Paris: Karthala.

Dungia, Emmanuel, 1993, Mobutu et l’argent du Zaïre. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Hochschild, Adam, 1998, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa.Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Human Rights Watch, 2002, The War within the War: Sexual Violence against Women and Girls in Eastern

Congo. New York: Human Rights Watch. International Crisis Group, 2000, Scramble for the Congo: Anatomy of an Ugly War, ICG Africa Report No. 26.

Nairobi and Brussels: ICG. International Rescue Committee, 2003, Mortality in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Results from a Nationwide Survey. New York: IRC.

Kalele-ka-Bila, 1997, “La démocratie à la base: l’expérience des parlementaires–debout au Zaïre”, in Georges

Nzongola-Ntalaja and Margaret C. Lee (eds), The State and Democracy in Africa. Harare: AAPS Books;

Appiah, K. A. (2006). Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

Clark, P. (2010). “Gacaca: Rwanda’s Experiment in Community-Based Justice for Genocide Crimes Comes to a Close.” Foreign Policy Digest (April). See www.foreignpolicydigest.org/Africa-2010/phil-clark.html.

Fanon, F. (1952, 2008). Black Skins, White Masks. New York: Grove Press.

Farah, A. Y., and I. M. Lewis. (1997). “Peace-Making Endeavors of Contemporary Lineage Leaders in ‘Somaliland,’” in Hussein M. Adam and Richard Ford (eds.), Mending Rips in the Sky. Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press, 317-25.

James, L. B. (1974). “Cultural Ideology and Helping Systems in Traditional African Cultures: A Transcontinental Perspective.” Unpublished research grant documentation. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University.

Jones, C. (2009). “The Impact of Racism on Infant Mortality.” Invited lecture, Ohio Department of Health, Infant Mortality Task Force, October 2009.

Kiplagat, B. (1998). “Is Mediation Alien to Africa?” The Ploughshares Monitor 19(4).

Myers, L. B. (1988/1992). Understanding an Afrocentric Worldview: Introduction to an Optimal Psychology. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.

Abdul-Raheem, Tajudeen, Biney Ama and Adebayo Olukoshi 2010. Speaking truth to power: Selected Pan-African postcards. CapeTown/Oxford, Pambazuka Press.

Achebe, Chinua 1996. Things fall apart. Expanded edition. Oxford/Portsmouth, NH, Heinemann Educational.

Ackerman, John 2004. Co-Governance for accountability: Beyond ‘Exit’ and ‘Voice’. World Development, 32 (3), pp. 447-463.

Adamoleku, Ladipo 1988. Political leadership in Sub-Saharan Africa: From giants to dwarfs. International Political Science Review, 9 (2), pp. 95-106.

Agulanna, Christopher 2006. Democracy and the crisis of leadership in Africa. The Journal of social, political, and economic studies, 31 (3), pp. 255-264.

Ali, Taisie M. and Robert O. Mathews 1999. Introduction. In: Taisier, Ali M. and Robert Mathew eds. Civil wars in Africa: Roots and resolutions. Montreal/Kingston/London

Depelchin, Jacques. Silences in African History. Dar-es-Salaam : Mkuki Na Nyota Publishers, 2004.

De Witte, Ludo, L’Assassinat de Lumumba : Paris : Editions Karthala, 2000.

Edgerton, Robert B. The Troubled Heart of Africa: A History of the Congo . New York : St. Martin’s Press, 2002.