IF YOU turned on the news in Saudi Arabia a decade ago, you were likely to see a relatively young, reform-minded prince who was bent on securing the kingdom’s future. Muhammad bin Nayef was out front, dealing with the country’s most pressing challenge, terrorism. He was clever, media-savvy and ambitious. There was little doubt that he wanted to be king.

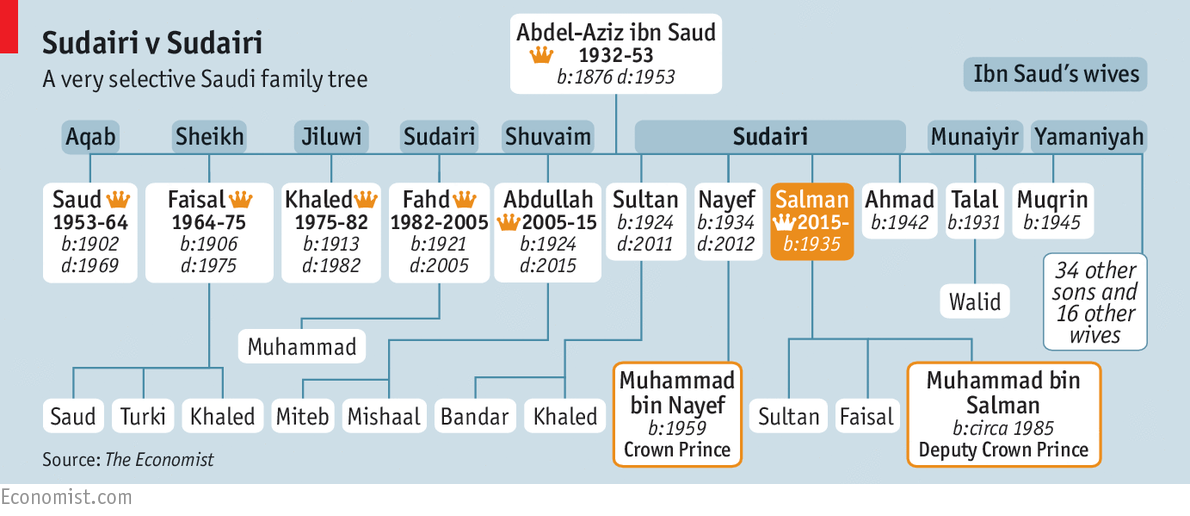

In April last year, four months after King Salman, his uncle, had ascended to the throne, he duly became crown prince. That was a dramatic break with tradition, because the past six kings of Saudi Arabia have all been sons of the founding monarch and several more are still alive. They were waiting in a brotherly queue. But at last it was decided that the succession would jump a generation. Prince Muhammad bin Nayef, now 57, is officially next up.

That now seems less certain. In the past year King Salman’s own much younger son, also a Muhammad, aged only 31, has burst onto the scene as minister of defence and deputy crown prince, tasked with weaning the kingdom off oil. Overshadowing his older cousin, he has hogged the limelight, promising a string of drastic reforms. King Salman seemed to be grooming him to be his immediate successor.

Crown Prince Muhammad is unlikely to take the mooted demotion lying down. He has been in tough spots before. He has survived several assassination attempts. In 2003 he bolstered his reputation by personally accepting the surrender of an al-Qaeda leader. In 2009 he was nearly killed at a similar meeting when a supposedly rehabilitated terrorist exploded a bomb apparently placed in his rectum.

This week Crown Prince Muhammad (or MBN, as he is known in diplomatic circles) represented Saudi Arabia at the UN general assembly in New York where world leaders congregate, dampening speculation that he may have been formally sidelined in favour of his young cousin. Although such speculation is taboo in the kingdom Saudis whisper about palace intrigue. Each prince respects the other in public, but signs of tension abound.

Take the Saudi-led war in Yemen, spearheaded by Muhammad bin Salman (MBS) just weeks after he became defence minister last year. At first he flaunted his leadership, meeting generals and visiting foreign capitals, always with the press in tow. But as the intervention turned sour, it was re-spun as a collective decision. Blame, in other words, should be shared. “What was noticeable was that Muhammad bin Nayef didn’t come rushing in to say, ‘Yes, that’s right’”, says Bruce Riedel of the Brookings Institution, a think-tank.

In December MBN seemed to go into a sulk. He went to Algeria, oddly staying there for six weeks and neglecting his duties back home. There has since been an effort to display harmony in the royal family. But if the crown prince did become king, he might well sack his young cousin. So the 80-year-old King Salman, whose faculties are said to be fading, may need to move fast if he wants his boy to succeed.

That may not be easy. The kingdom has traditionally been ruled by a royal consensus. Many princes are loth to let MBS jump the queue. The war in Yemen is already an albatross around his neck. His economic reforms are causing real pain.

Moreover, the crown prince is well liked. Saudi royals and Western diplomats praise him as serious and hard-working. Ordinary Saudis view him as their protector. He boosted his standing this month by overseeing a tranquil haj, the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca, marred last year by a deadly stampede. Human-rights groups are less impressed, blaming him—among other things—for the execution in January of a Shia cleric accused of terrorism. But he seems steadier than his youthful cousin. As the kingdom undergoes an economic shake-up, no one is sure who will lead it. The only thing you can bet on is that his first name will be Muhammad.