-

25 September 2016

- World

Date: Sun, 25 Sep 2016 16:26:19 +0200

How Ethiopian prince scuppered Germany's WW1 plans

A hundred years ago, the Ethiopian prince Lij Iyasu was deposed after the Orthodox church feared he had converted to Islam. But it also scuppered Germany's plans to draw Ethiopia into World War One, writes Martin Plaut.

In January 1915 a dhow slipped quietly out of the Arabian port of Al-Wajh. On board were a group of Germans and Turks, under the guise of the Fourth German Inner-Africa Research Expedition.

Led by Leo Frobenius, adventurer, archaeologist and personal friend of the German Emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, its aim was nothing less than to encourage Ethiopia to enter World War One.

Germany believed that the Suez canal was Britain's "jugular vein" allowing troops and supplies to be brought from Australia, New Zealand and India.

The war plan

An assault on the canal by Turkish and German forces had been repelled in early 1915, but it was clear that this was not the final attack.

Ethiopia - an independent nation - was the major power in the region and Germany believed that if it could persuade the Ethiopians to enter the war on its side, British and allied forces would have to be withdrawn from the Canal and other fronts.

The aims of the General Staff in Berlin were: "To force the enemy to commit large forces in defending their colonies in the Horn of Africa, thus weakening their European front and relieving the German forces fighting in German East Africa."

This called for "insurrection" in Sudan with the aim of toppling British rule and attacks on French-ruled Djibouti and Italian Eritrea.

"The colonial Italian and French possessions on the shore of the Red Sea were difficult even impossible to defend without [the] commitment of large forces: chances were that an Ethiopian blow against the shores of the Red Sea and Suez Canal would either succeed at once, or that Italy and France would voluntarily withdraw in view of the critical situation of the European front, where all men and rifles were badly needed after the initial military successes of the Central powers."

In Berlin's view, the "double threat" of internal insurrection in Sudan and an Ethiopian offensive would pave the way for a successful attack on the Suez Canal by Turkish forces "supported by a German expeditionary force".

The loss of the Canal would be a decisive blow against Britain and its allies, from which it would be unable to recover.

Mission failure

It was with this objective in mind that Frobenius was despatched to Ethiopia, with orders which mirrored the plans drawn up by the British for an Arab uprising against the Ottomans - plans which resulted in the Arab Revolt of 1916 and the legend of "Lawrence of Arabia".

The Frobenius expedition landed in the Italian colony of Eritrea on 15 February but the Italians, who were British allies, arrested them.

Forbenius was deported back to Berlin, but the German high command were determined that this would not be the end of the story.

A fresh expedition was despatched in June 1915, this time led by Salomon Hall, who came from a Jewish Polish family with long ties to Ethiopia.

Again he was intercepted in Eritrea. Keen-eyed police spotted that although he wore sandals, he had corns, and was clearly not the Arab he was pretending to be.

Although the Hall mission failed, copies of the documents he carried reached the German mission to Ethiopia in October.

The German envoy in Addis Ababa, Frederick Wilhelm von Syburg, was instructed to do everything possible to convince the Ethiopian government to enter the war.

Von Syburg was ordered to explain to the Ethiopians that Germany had scored "great victories" in the war and made lavish promises of what might follow.

"Now the time has come for Ethiopia to regain the coast of the Red Sea driving the Italians home, to restore the Empire to its ancient size...

"Germany commits herself to recognize any territory which Ethiopia may conquer or occupy in military action against the Allied powers as being her rightful and permanent property and part of the Ethiopian Empire after the war."

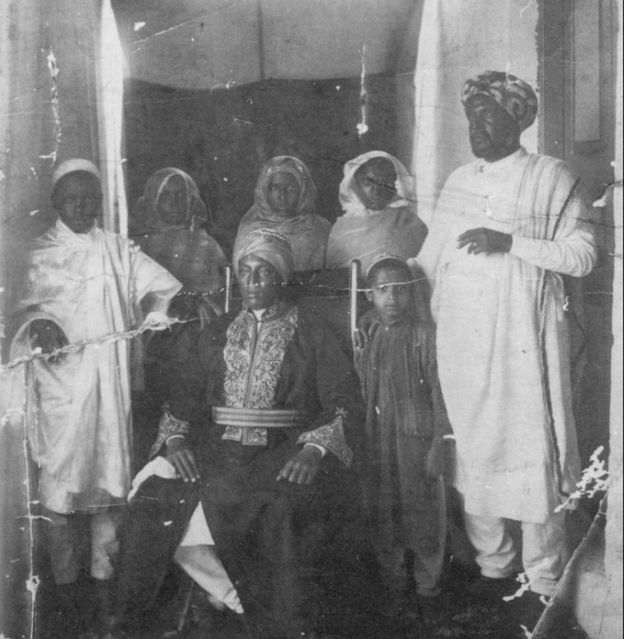

These plans found a ready audience with the heir to the Ethiopian throne, Lij Iyasu. The prince, who was never crowned, had become the effective ruler after his grandfather, Emperor Menelik II suffered a massive stroke in 1909, finally dying in December 1913.

On 10 April 1911 the 16-year-old Iyasu took the opportunity of the death of the regent, to claim personal rule. He was hardly ready for the position.

As historian Harold Marcus wrote: "The youth was hardly ready to govern: during his adolescence, he had mostly abandoned the classrooms for the capital's bars and brothels. He had a short attention span, and lacked political common sense, if not a grand vision."

That vision included reaching out to the Muslim peoples whom his grandfather had conquered during his expansion of Ethiopian rule from the Christian highlands into the surrounding Muslim lowlands.

Muslim empire

Lij Iyasu sent much of his time outside the capital, touring the Somali and Afar regions of his country. Iyasu was encouraged by the Ottoman envoy to Ethiopia, Ahmad Manzar.

Iyasu took a number of Muslim wives and soon rumours began spreading that the prince had adopted Islam himself.

Although his ancestors had included Muslim nobility who had converted to Christianity, the idea that Iyasu returned to Islam is contested by scholars.

What is clear is that the prince was very friendly with Muslims, including a longstanding British enemy, Sayyid, Muhammad Abd Allah al-Hassan, (known as the "Mad Mullah") of Somaliland.

Iyasu - encouraged by the Ottomans - sent weapons and ammunition to the Sayyid. Turkey went further, promising that it would land troops to back the Sayyid.

By 1916 most of the pieces were in place. Iyasu appeared to have decided to throw in his lot with the Ottoman and German cause.

He was reinforced in this view by the Turkish successes in Gallipoli and Mesopotamia.

Matters came to a head in September. Reports began to circulate that Iyasu had presented an Ethiopian flag with a Red Crescent and a quotation from the Koran to Somali troops.

As historian Haggai Erlich concluded: "His steps cannot be interpreted other than leading towards a new Ethiopia, centred on Harar as the capital of an Islamic, African empire, allied with Istanbul and under his rule."

Excommunicated

The Ethiopian nobility and the church, fearing for the future of their nation as a bastion of Christianity, decided to act.

The head of the Orthodox church was persuaded - somewhat reluctantly - to excommunicate Iyasu.

On 27 September 1916, the prince was deposed. Iyasu fought back, but his troops were defeated and he fled into hiding. Iyasu was only captured in 1921, when he was finally imprisoned.

Ras Tefari - crowned Haile Selassie in 1930 - was placed on the throne.

Britain, France and Italy had encouraged the coup by lobbying the Ethiopian elite to act against Iyasu.

On 12 September, the Tripartite powers sent a formal message to the Ethiopian foreign minister complaining that Iyasu was supporting rebellion in Somaliland and demanded an immediate explanation.

With the prince out of the way, they breathed a collective sigh of relief.

As Thesiger informed the Foreign Office: "the Government is now in the hands of those who are friendly to our cause." The threat that Ethiopia might enter the war was at an end.

The attempt to set Ethiopia on a new course as part of Kaiser Wilhelm's dream of inflaming the "whole Mohammedan world with wild revolt" had come to nought.

There had been no landing of Turkish or German troops from the Red Sea. Yet it had been a close-run thing.

If the Arab Revolt had not taken hold on the opposite side of the Red Sea and Iyasu had not played his cards quite so poorly, the outcome might have been very different, with catastrophic implications for Britain and its allies.