Image copyright Reuters

Image copyright Reuters Date: Fri, 7 Oct 2016 23:54:24 +0200

Image copyright Reuters

Image copyright Reuters Political protests which have swept through Ethiopia are a major threat to the country's secretive government, writes former BBC Ethiopia correspondent Elizabeth Blunt.

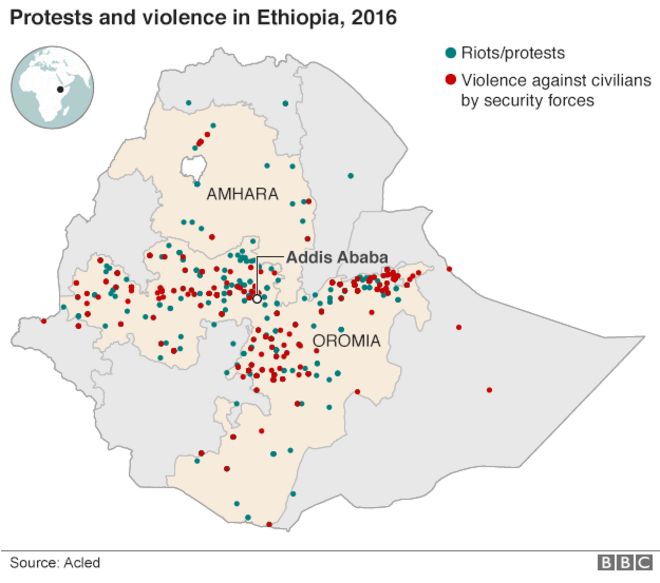

For the past five years Ethiopia has been hit by waves of protest, not only by formal opposition groups but also Muslims unhappy at the imposition of government-approved leaders, farmers displaced to make way for commercial agriculture, Amhara communities opposed at their inclusion in Tigre rather than the Amhara region and, above all, by groups in various parts of the vast Oromia region.

In the most recent unrest in Oromia, at least 55 people died when security forces intervened over the weekend during the annual Ireecha celebrations - a traditional Oromo seasonal festival.

The Oromo protests have continued long after plans to expand the capital Addis Ababa's boundaries to take in more of the region were abandoned earlier this year. And in the last few months groups which were previously separate have made common cause.

In particular, Amhara and Oromo opposition has coalesced, with both adopting the latest opposition symbol - arms raised and wrists crossed as if handcuffed together.

The picture of Olympic silver medallist Feyisa Lilesa making this gesture while crossing the finish line at the Rio 2016 went round the world, and photographs from the Ireecha celebrations in Bishoftu show the crowd standing with their arms crossed above their heads before police intervention triggered the deadly panic.

The ruling coalition, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), has some solid achievements to show for its 25 years in power, in terms of economic development and improved health and education, especially for the rural poor.

But what it has not been able to do is manage the transition from being a centralised, secretive revolutionary movement to running a more open, democratic and sustainable government.

'Inflaming anger'

In theory, Ethiopia has embraced parliamentary democracy, but such hurdles are put in the way of potential rival parties that there are currently no opposition members of parliament.

The EPRDF has in theory devolved a good deal of power to the country's ethnically based regions, but time and again regional leaders have been changed by central government.

Ethiopia's constitution allows freedom of speech and association but draconian anti-terrorism laws have been used against those who have tried to use those freedoms to criticise the government.

It is now clear that these attempts to hold on to control in a changing world have misfired.

Just as attempts to dictate who should lead the Muslim community led to earlier protests, reports from Bishoftu town, where the 55 died, say that anger spilled over on Sunday because of official attempts to control which Oromo leaders were allowed to speak at the event.

The overreaction of the security forces then turned a protest that might have gone largely unnoticed into a major catastrophe, inflaming anger in Ethiopia itself and causing growing concern abroad.

And so the cycle continues, and every time protests are badly handled they create more grievances, and generate more anger and more demonstrations.

The US government is among those who have expressed concern at the deteriorating situation. Its Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, met Ethiopia's Prime Minister Hailemariam Dessalegn during the UN General Assembly last month.

She urged him to be more open to dialogue, to accept greater press freedom, to release political prisoners and to allow civil society organisations to operate.

Ethiopia's ethnic make-up

- Oromo - 34.4%

- Amhara - 27%

- Somali - 6.2%

- Tigray - 6.1%

- Sidama - 4%

- Gurage - 2.5%

- Others - 19.8%

Source: CIA World Factbook estimates from 2007

"We have encouraged him to look at how the government is addressing this situation," she said after the meeting.

"We think it could get worse if it's not addressed - sooner rather than later."

Oromo PM hopes dashed

The latest reports from Ethiopia show why concerted opposition from Oromia is such a potential problem for the government.

The Oromos are the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia, and they have a long-standing grievance about the fact that despite this they have never controlled the political leadership.

More on Ethiopia's unrest:

- What is behind Ethiopia's wave of protest?

- Endurance test for Ethiopia's Feyisa Lilesa

- The town from where Fesiya comes

- What does unrest mean for Ethiopian unity?

- Why Ethiopia is making a historic ‘master plan’ U-turn

Amhara domination, under Ethiopia's former military government and emperors, was replaced by Tigrean leadership following the overthrow of long-serving ruler Mengistu Haile Mariam in 1991.

Meles Zenawi, who played a key role in the rebellion to overthrow the Mengistu regime, took power, serving as president and later as prime minister.

When he died in 2012, the Oromo hoped it would be their turn to rule, but his chosen replacement, Mr Hailemariam, came from the small Welayta ethnic group in the south.

Not only are the Oromo numerous, their region is large and more productive than the densely populated highlands.

It produces a lot of Ethiopia's food, and most of its coffee, normally the biggest export earner.

The sprawling region encircles Addis Ababa, controlling transport routes in and out of the city.

For a government so worried about loss of control, big Oromo protests are a serious threat indeed.