IT WAS meant to have been a time for celebration. When on October 5th the Ethiopian government unveiled the country’s new $3.4 billion railway line connecting the capital, Addis Ababa, to Djibouti, on the Red Sea, it was intended to be a shiny advertisement for the government’s ambitious strategy for development and infrastructure: state-led, Chinese-backed, with a large dollop of public cash. But instead foreign dignitaries found themselves in a country on edge.

Just three days earlier, a stampede at a religious festival in Bishoftu, a town south of the capital, had resulted in at least 52 deaths. Mass protests followed. Opposition leaders blamed the fatalities on federal security forces that arrived to police anti-government demonstrations accompanying the event. Some called the incident a “massacre”, claiming far higher numbers of dead than officials admitted. Unrest billowed across the country.

On October 8th, a week after the tragedy at Bishoftu, the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) announced a six-month state of emergency, the first of its kind since the former rebel movement seized power in 1991. The trigger was not clear: violent clashes between police and armed gangs, and attacks on foreign-owned companies, had been flaring across the country for several days (and have occurred sporadically for months) but seemed to have plateaued by the weekend. On October 4th an American woman was killed while travelling outside the capital. Protesters have blockaded several roads leading in and out.

One factor in the government’s decision was a spate of attacks on holiday lodges at Lake Langano, and on Turkish textile factories in Sebeta, both in the restive Oromia region south of the capital, on October 5th. The attackers were well-organised and armed, some of them reportedly mounted on motorbikes. These acts, officials suggest, were the final straw.

The government is rattled by the prospect of capital flight. An American-owned flower farm recently pulled out, and it fears others may follow. After almost a week of silence, the state-of-emergency law was a belated attempt to reassure foreign investors, who have hitherto been impressed by the economy’s rapid growth, that the government has security under control.

A calm of sorts now prevails. On October 10th parliament, which since last year’s elections has been entirely populated by members of the EPRDF and its allies, heard details of the decree, which it is expected to formally approve. The bill provides for sweeping powers of arrest and a draconian ban on free assembly and expression. The prime minister, Hailemariam Desalegn, was confident enough to attend to diplomatic pleasantries. Germany’s chancellor, Angela Merkel, arrived in the capital the following day to talk about refugee flows from the region. Mobile internet access, which the government blocked in order to disrupt the protests, flickers occasionally and feebly back to life. The hustle and bustle of Addis Ababa continue as before, though an uneasy silence has settled across towns like Bahir Dar in the Amhara region where strikes have emptied the streets for weeks. In Addis Ababa, at least, a mood of resignation has taken hold. Better dictatorship than civil war, residents shrug.

Still, the future is troubling. Over 500 people have been killed since last November, and tens of thousands have been detained. What began nearly a year ago as an isolated incidence of popular mobilisation among the Oromo people, who make up at least a third of the population and opposed a since-shelved plan to expand Addis Ababa into their farmland, has spread. It is now a nationwide revolt against the authoritarianism of the EPRDF and the perceived favouritism shown to a capital whose breakneck development appears to be leaving the rest of the country behind.

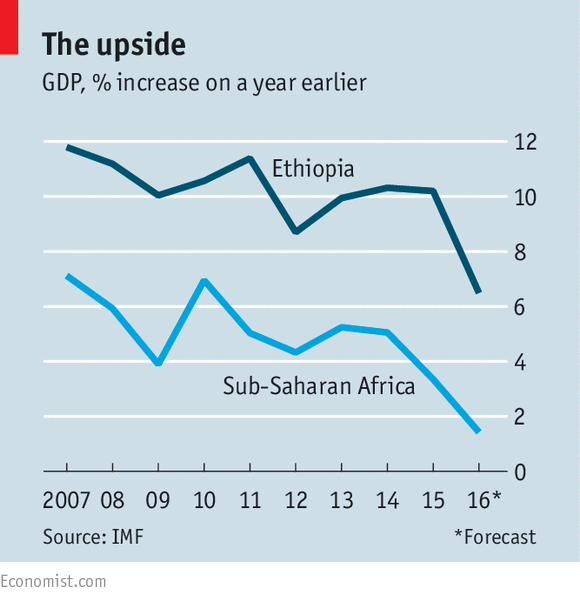

The young are frustrated. They feel that growth has yet to bring the broader prosperity promised by the government in return for their political obedience. Thanks in large part to foreign aid, expansive public spending supported by Chinese loans and an uptick (from a very low base) in foreign investment, Ethiopia was Africa’s fastest growing economy in 2015—a remarkable feat for a still largely agrarian country. But the expectations of an increasingly educated population have grown even faster. Despite big strides, a third of Ethiopians, who now number nearly 100m, still live on less than $1.90 a day.

The Oromos are not the only ones with grievances. Many others have been driven off their land to make way for commercial farms and factories. And the Amharans, who have historically been Ethiopia’s dominant ethnic group, resent the leadership of the much smaller Tigrayan group (who make up around 6% of the population) at the heart of the ruling EPRDF. The comparative quiescence of Addis Ababa’s citizens has further fuelled resentment. Angry farmers in parts of the country have been choking the movement of goods towards the city. The opposition calls for political prisoners (who are reckoned to number in the thousands) to be freed, but the government is in no mood to oblige. However, on October 10th the president promised to introduce some form of proportional representation in elections, which would allow all groups a share of power.

Tinkering is unlikely to be enough. The EPRDF has weathered storms before. Civil strife after disputed elections in 2005 resulted in at least 193 deaths and many thousands of arrests. This time Ethiopians are calling just as fiercely for regime change, and not just reform. Ethiopia, until recently a darling of Western donors and security hawks alike, is edging closer to the brink.

Correction (October 13th): The original version of this article said that parliament had rubber-stamped the state-of-emergency law; it had not. This has been corrected.