OVER 9,000 people have died in Yemen since Shia rebels, the Houthis, forced the government into exile, prompting a Saudi-led military intervention in March 2015. Some 3m people have been displaced. Cholera has struck Sana’a, the capital, and the threat of famine looms. Yet the suffering in the Arab world’s poorest country has been overshadowed by the far bloodier conflict in Syria.

That changed on October 8th, when two missiles, probably from Saudi aircraft, tore through a crowded funeral hall in Sana’a, killing more than 140 mourners and wounding over 500. Even for Yemen, a country accustomed to violence, the carnage was shocking. The attack has finally drawn attention to the “forgotten war”, which has intensified since peace talks broke down in August. It may also alter the course of the deadlocked conflict.

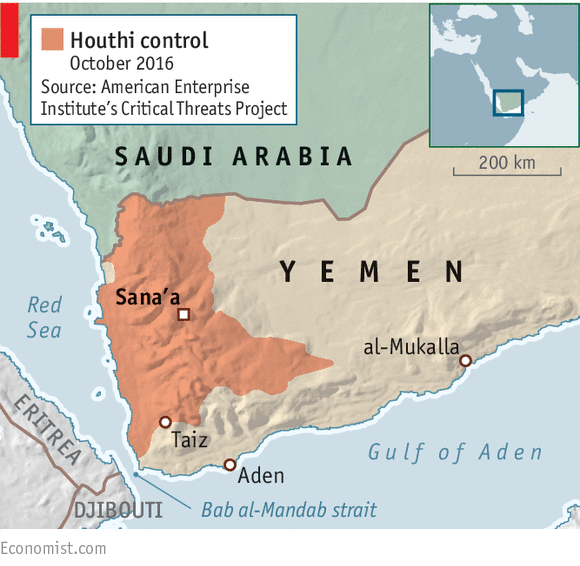

Among the dead were members of several powerful tribes from northern Yemen, including supporters of peace talks such as Abdulqader Hilal, the mayor of Sana’a. Survivors now speak of revenge. Analysts fear they will line up with the Houthis, who have already stepped up their attacks on Saudi Arabia—and, perhaps, America. On two occasions this week missiles were fired from Houthi-held territory at an American destroyer in the Bab al-Mandab strait, though none hit the ship. The Houthis deny launching the attack, but on October 12th America struck back at Houthi radar sites.

Officials in Washington have long worried that America may be implicated in Saudi atrocities. It has backed the bombing campaign, providing targeting advice and refuelling sorties that have allowed Saudi jets to linger over the war zone. But America is now reviewing that support, which was offered, in large part, to allay the kingdom’s concerns over a nuclear deal with Iran, the main backer of the Houthis.

The commitment has proved larger than expected for America. A bombing campaign that was meant to be short and defensive in nature is now in its 20th month. Saudi-led air strikes were responsible for 60% of civilian deaths in the year starting in July 2015, according to the UN. In total over 4,000 civilians have died in the fighting. This is the result of ineptitude, not malice, say American officials. But they have already pulled back some support.

The Saudis have struck schools, hospitals and critical infrastructure, despite using precision-guided bombs made in America. They blame the Houthis for fighting near civilians. The UN has also accused the group of using human shields. But a Dutch proposal to set up an independent UN inquiry was reportedly blocked by Britain, an ally of Saudi Arabia, in September.

Some in America and Britain propose cutting off arms sales to Saudi Arabia. Others want them to use their leverage to push harder for peace. John Kerry, America’s secretary of state, has called for an immediate ceasefire. But he has struggled to restart peace talks. Abd-Rabbo Mansour Hadi, the unpopular president in exile, seems reluctant to give up his claim to power. The Houthis have balked at demands that they cede their weapons and territory before a unity government is formed.

Earlier this month, the Houthis announced the creation of a government of “national salvation” that is meant to rival the administration of Mr Hadi, which has international recognition. In his own assertion of authority, Mr Hadi has moved the country’s central bank from Sana’a to the southern city of Aden, where his government has a foothold. Some analysts fear, however, that the move will disrupt the bank’s activities and exacerbate the country’s economic crisis.

“Surely enough is enough,” said Stephen O’Brien, the UN’s emergency relief co-ordinator, in response to the attack on the funeral. But new reports of civilian deaths are coming in from the central city of Taiz, under siege by the Houthis and forces loyal to their ally, Ali Abdullah Saleh, a former dictator. Neither side has exhausted its capacity to create misery.