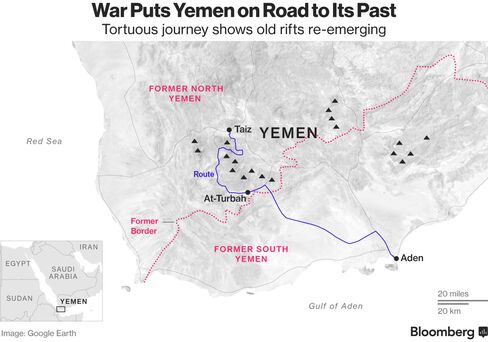

It used to take two and half hours to make the simple trip from the Yemeni city of Taiz to Aden on the southern coast. Lately, it could take an entire day using jeeps and donkeys across a mountain pass and checkpoints, showing how another Arab country is at risk of being irreversibly carved up by conflict.

More than five years after Yemen was swept up by the jubilation and turmoil of the Arab Spring, it is now a cauldron of proxy war that pits Iran against a Saudi Arabia keen to keep its arch-rival out of its backyard. The war’s mounting death toll—10,000 at the latest count—is overshadowed by even greater carnage in Syria and mostly ignored by a world confused by the complicated politics of a country few understand.

But Yemen matters, not only because people are dying. Its location makes it a potential staging point for attacks on the world’s biggest oil producer and a breeding ground for Islamist extremism. The carnage is unleashing yet another humanitarian disaster in a region that’s already being ripped apart.

The reality is “no one knows how to address the problems in Yemen and no one is willing to commit the resources or attention,” said Graham Griffiths, an analyst at Control Risks in Dubai. “We’re unlikely to see stability brought to the country or a functioning central government re-established that controls all of Yemen’s territory. It will certainly remain a safe haven for groups like al-Qaeda and possibly the Islamic state.”

North V. South

The war pits a Saudi-backed government that controls most southern territories against pro-Iranian Shiite Houthi rebels who control the capital Sana’a in the north. The two regions were separate countries that only unified in 1990. A southern attempt to secede in 1994 was crushed by then-President Ali Abdullah Saleh, the main ally of the Houthis in the current conflict.

Few experiences illustrate the country’s deepening fractures than traveling between the north and south. Having friends who can vouch for you makes it easier to pass security checkpoints into either territory. Taking a woman along on a trip can help because it means you’re less likely to be searched or questioned.

Months after the conflict broke out in 2015, residents of Taiz, Yemen’s industrial hub and the main gateway to the south, had to use a boulder-strewn pass across mountains to take the 270-kilometer (168-mile) journey south to the coast after the roads to the city were blocked by the Houthis and allied forces to continue to impose a siege on the city.

That meant the journey took 14 hours on a path teeming with men, women and children. Some are trying to flee, others had been hired—for less than $2 a trip—as porters to bring food and medicine into the city. Donkeys hauled heavier loads and there were even camels loaded with weapons destined for pro-government fighters. Jeeps crawled up less steep sections.

Dead Donkey

On one journey, some of the travelers cracked jokes and sang folk songs as they made their way up the pass, even as they lamented a conflict that they feel is dragging Yemen back centuries. When a donkey fell off the trail and died, anti-Houthi activists praised the animal for its “remarkable contribution in alleviating the suffering of the people of Taiz,” a sardonic dig at the failure of the Saudi-backed government to end their plight.

Those who fled left behind a city that is now full of gunmen. Streets, once bustling, are more accustomed to bloodshed. Just going out to buy bread can be fatal.

No Surrender

Control of Taiz offers a strategic advantage, though locals say their besiegers are as much driven by revenge. It was in Taiz that the 2011 revolt that ended President Saleh’s rule began. Residents say the Houthis want to punish the city for spearheading protests against their armed takeover.

“Saleh is taking revenge on Taiz, and wants to rule us by force or kill us,” Samirah, a woman wearing the traditional dress of the Sabir mountain region, said on one of the trips across the pass. It won’t work, she said: “We’re ready to sacrifice more rather than surrender.”

Only a few factories are operational, most in areas controlled by the Houthis or their allies. Just four public and private hospitals out of 39 are open, and they can’t accommodate all the sick and injured. Medical supplies are running low. At the start of the conflict, gasoline prices surged to about $10 per liter, up from $0.69 before the war, though prices have since come down to below $3.

The rest of the country isn’t in a better situation. More than 140 people were killed when the Saudi-led coalition attacked a funeral hall in Sana’a this month. The coalition said the attack was a mistake. In Aden, more than 50 people died in a suicide attack that targeted recruits joining forces fighting the Houthi in late August.

And while the U.S. military retaliated against missiles fired at a Navy ship this month, there are few signs that resolving the conflict is seen as a priority by western powers, according to Griffiths at Control Risks.

“Yemen is likely to remain a second tier item on the U.S. and other countries’ agenda,” he said.

--With assistance from Zainab Fattah and Caroline Alexander.