The Uprooted

Part Two

A Scientific Survey of Ethnic Eritrean Deportees

from

Ethiopia

Conducted with regard to Human Rights Violations

Prof. Asmarom Legesse 1

on behalf of Citizens for Peace in Eritrea 2

Asmara, Eritrea, 22 February 1999

Table of Contents

- Background

- Presentation

- Citizenship of the Deportees

- Do deportations have legal authority? Who authorizes them?

- The Confiscation of Private Homes

- Alleged Crimes Committed against Ethiopian National Security

- Cruel and Inhuman Conduct: Break-up Families

- Cruel and Inhuman Conduct in the Deportation Process

- The Deportees in Eritrea

- Conclusion

- Footnotes

- Appendices

Background

A human rights crisis is looming large on the horizon in the Horn

of Africa,

resulting from the impact of a border-conflict between Ethiopia and

Eritrea: since the

outbreak of hostilities in May 1998, ethnic Eritrean citizens of

Ethiopia and Eritrean

nationals who are residents in Ethiopia have been and are being

deported to Eritrea at the

rate of about 7000 people per month. The purpose of this study is to

examine whether and

what kind of the human rights violations have been committed in the

process of those

deportations.

The immediate cause of the war was a border conflict in which

both countries claimed

territories along an international boundary, established in the

early part of our century by a

series of treaties between the Governments of Ethiopia and Italy --

the colonial power then

in control of Eritrea. Intense negotiations are now in progress in

the Organization of

African Unity which is attempting to mediate the conflict and get

both parties to agree on

the temms on which the intemational boundary can be demarcated on

the ground.

Illegal Mass Deportations from Ethiopia 3

The treatment of civilians in war situations is governed by the

conventions and

covenants of the United Nations. Mass deportations from Ethiopia are

the product of a

deliberate and declared policy which was spelled out by Prime

Minister Melles Zenawi as

the incontestable right of his government. 4

However, our data reveal that the deportation of ethnic Eritreans

and the manner it is being

carried out violates the UN Charter on Human Rights, the

International Covenant on Civil

and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Convention on the ri~hts of the

Child and the Geneva

Conventions.

In contrast to the mass deportations from Ethiopia, Eritrea has a

declared policy of not

harassing or expelling the large Ethiopian population that lives in

its territory. When

Ethiopia placed an embargo on Eritrean ports in May 1998 -- ports

which were, until then,

Ethiopia's principal outlets to the sea -- the very large Ethiopian

population living in the

port of Assab became unemployed and began to return to Ethiopia.

Since some of these

returnees were falsely claiming that they had been harassed, robbed,

raped and forcibly

expelled from Eritrea, the country asked the International Committee

of the Red Cross

(ICRC) to oversee the entire process by which Ethiopians voluntarily

depart from Eritrea.

That procedure has been in operation for several months, since

August 1998. Ethiopia later

claimed that a similar procedure was in force on the Ethiopian side

but ICRC, in a message

addressed to the Eritrean ambassador in Addis Ababa, stated that

there was no such

procedure which they have been allowed to oversee. 5

Eritrea has adhered to its own stringent code of conduct

throughout the current "border

crisis." It has invited or allowed independent observers such as

ICRC, Amnesty

International, Africa Watch, the UN agencies in Eritrea, the

European Union representative

in Eritrea and the UN Commission for Human Rights to verify the

situation of Ethiopians

in Eritrea and determine whether or not they are being harassed or

forcibly deported. 6 EPLF, the front which liberated Eritrea and

established the

independent state, has adhered to its longƒstanding code of

conduct with regard to

the ethical standards to be maintained in times of war. To day the

Government of Eritrea

maintains those standards not because of international pressure or

because of international

conventions to which they are a party, but because Eritrea's ancient

as well as revolutionary

traditions of the rule of law compels them to do so. 7

The evidence so far

In the human rights arena the evidence against Ethiopia is

mounting. Among the

many reports that support our earlier findings on the deportees are

a study by Natalie Klein,

a solicitor with the Australian Supreme Court 8

and reports by the representatives of Amnesty International 9

, Human Rights Watch World Report 1999, 10

the European Union Representative in Eritrea, US State Departmentl

11

, UNICEF, Eritrea 12

, and the UNDP chief in Asmara representing all the UN agencies. 13

They have all documented different aspects of human rights

violations in the recent

Ethiopian deportation campaign. Nearly all of them have also

established that there is no

significant or extensive evidence of human rights violations on the

Eritrean side or that

most Ethiopians who left Eritrea did so voluntarily or because of

changes in the labor

market. In the face of this body of evidence, it is unethical for

some diplomats and news

organization to say, repeatedly, that "both nations are deporting

each others citizens"

without examining the available evidence cited above or

independently verifying the claims

of the two countries.

Mary Robinson - the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights - took

bold action in

condemning Ethiopia on the basis of the evidence that was available

to her. 14

The reaction to her comment from Ethiopia was high handed and

strident. An example is

the interview by Prime Minister Meles Zenawi of July 9, 1998 in

which he repeatedly

questions the competence of the High Commissioner and refers to her

as "that woman."

(See Appendix 4) Unlike some segments of

the diplomatic

community, however, she has not buckled under in the face of

Ethiopian condemnation.

The government of Ethiopia ought to know that it is not possible to

hide human rights

violations when deporting tens of thousands of ethnic Eritreans,

allegedly because they

were "security risks." In all our inquiries, we have not found a

single instance in which

Ethiopian authorities demonstrated these alle~ations in court, as

intemational law requires

them to do.

The Uprooted, Part I, Qualitative Data and in depth Interviews

Dur first report on the deportees, titled "The Uprooted," was

based on in-depth

qualitative descriptions of the experiences of individual deportees.

The data were

accompanied with verbatim transcripts of their testimony. On the

basis of the insights

gained from these profiles, we constructed a survey instrument -- a

questionnaire with 152

pre-coded variables representing different types and measures of

violations of rights

enshrined in the UN Declaration of Human Rights, the Covenant on

Civil and Political

Rights, and the Rights of the Child. In this second phase of our

research we have also

examined violations of the Geneva Conventions.

The Uprooted, Part II: Quantitative Survey and the Scientif -

Method Employed

Whereas our first report consisted of profiles of individuals

whose experiences

could not be shown to be representative of the larger population of

deportees, our present

survey is based on a properly randomized scientif c sample and,

thus, achieves that very

purpose. It is fully representative of the 6880 households from

which the sample was

drawn and, thus, the characteristics of the sample describe the

characteristics of the

population with a known mar~in of error.

The target sample size was 370. This is the minimum sample

required to reach the 95%

confidence interval with a population base of up to 10,000 cases. To

enable us to carry out

reliable analyses, even when there is missing data on particular

variables, we took a larger

sample than the minimum required. The final sample was 413

individuals selected from a

population base of 6880 cases which were mostly households. Hence,

we could have as

many as 43 missing observations ("no data " in our tables) on any

one variable and stiUget

reliable results, i.e. we would still reach the 95% confidence

interval -- the level we

adopted as a target for the whole study. The sampling procedure is

discussed in greater

detail in Appendix 1.

Given this approach, it is then possible to treat the sample as

being representative of

the population and to make inferences about the characteristics of

the population based on

our empirically determined characteristics of the sample.

Presentation of Data

We now go into the main body of our research and present each

group of

variables under several different headings:

Who are the deportees? What are their citizenship rights? Who

authorizes the

deportations? What happens to the property of deportees? What is the

background and role

of deportation personnel? Does the Ethiopian judiciary play any role

at all in the

deportations? What rights of the deportees are being violated?

Who are the deportees?

In terms of citizenship, the Eritrean population of Ethiopia

consists of two

groups: Eritrean citizens and Ethiopian citizens. Both populations

also fall into two other

categories:

Rural communities located near the Ethiopian-Eritrean border, who

have been evicted

from their farms and now live deeper inside Eritrean territory as

internal refugees.

Urban communities in a few centers in Ethiopia mainly engaged in

productive

economic, professional and technical activities, now being deported

to Eritrea.

Our focus in this study is entirely on the urban population.

These fall into four large

categories: those who have been deported, those waiting to be

deported (many of them with

suitcases packed), those who believe they will not be deported, and

those who are in a

variety of jails and concentration camps, with no hope of being

deported. Our study has

yielded systematic data on the first and anecdotal information on

the second. We have little

information about the last two categories, mainly because the

evidence is not within our

reach. We hope and trust that our Ethiopian counterparts in the

human rights field will

gather and publish information condemning the plight of this

population and the situation of

Ethiopians who have returned to Ethiopia from Eritrea for whatever

reason.

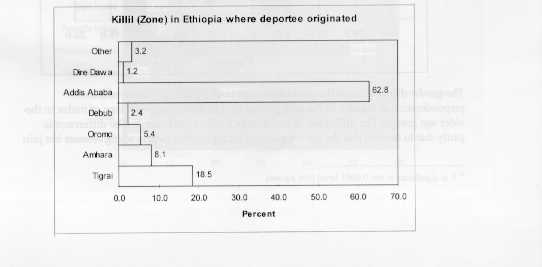

The Zone (Killil) of Ethiopia from which the deportees came

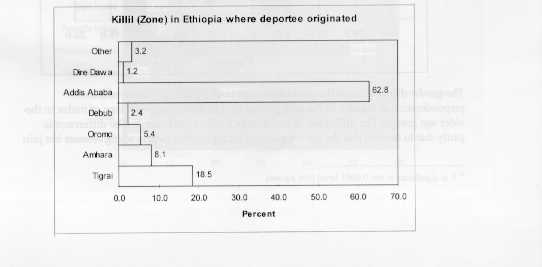

It is clear, from the graph below, that most deportees come

from Addis Ababa

and the rest come from the Tigray, Amhara, and Oromo zones. They are

overwhelmingly

urban and concentrated in the capital city. Since Eritrean citizens

of Ethiopia have no zone

of their own, they gravitate toward Addis Ababa, a multi-ethnic

city.

The fact that the next biggest concentration comes from Tigray

has ethnic, linguistic,

historic, and geographic reasons. The Tigrayans and the highland

Eritreans are next door

neighbors, they speak the same language, and have a common history.

However they

diverge sharply from each other in culture and character. The

divergent developments are

not merely a function of the colonial experience of Eritrea: the

divergence goes back to the

fourteenth century when Eritrea began writing her own customary laws

and developing her

own grass roots democratic institutions. The deep antipathy that

some Tigrayans have now

developed toward ethnic Eritreans is, however, a new phenomenon and

will probably

subside once the hate campaign runs out of steam.

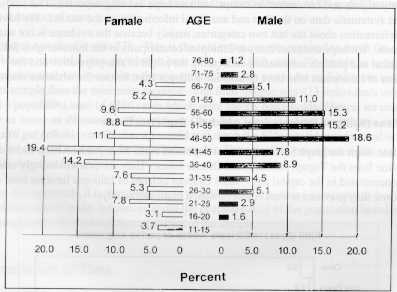

Social profile of the deportees

The deportees who have come to Eritrea are in a state of

disarray and it is not

possible to present a normal sociological picture of them. Their

homes and family lives

have been shattered. They are now trying to pick up the pieces and

start anew. The adult

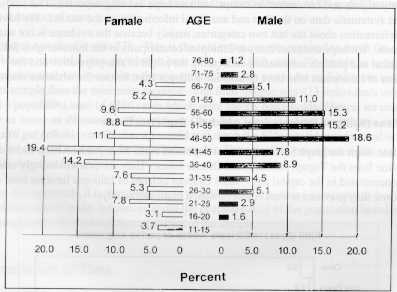

population we have surveyed consists of 70 percent males, 30 percent

females. These

individuals are mostly household heads or individuals who came to

Eritrea alone or with

part of their families. They are now living as "dependents" attached

to other families.

The gender distribution. of the population; is skewed by age, in

that there is a

preponderance of females in the younger age groups and a

preponderance of males in the

older age groups. The difference is statistically highly

significant. 15

The difference is partly due to the fact that the Government of

Ethiopia often expels young

women but jails

young men who are allegedly engaged in activities that are said

to be a security threat.

At the same time they also expel a disproportionately large number

of males of retirement

age or retirees on pensions who are an economic burden to the

regime. They are men (and

women) who spent a lifetime working for the Ethiopian government and

its parastatals,

now conveniently thrown out of the country.

The household status of the deportees can be better described in

terms of the family

structure they left behind in Ethiopia rather than the unstable and

very partial structures that

exist in their Eritrean homes today. Before their deportation, 74. 8

percent of the deportees

were household heads, 9.9 percent were dependents, and 14.8 percent

were single adults,

including those who are unmarried, divorced or widowed. Prior to

their arrival in Eritrea

about one third of the deportees (34.4%) were homeowners and many

owned very

substantial homes. The rest lived in rental housing.

Home Ownership in Ethiopia

| |

Percent |

Count |

|

Homeowner |

34.4 |

142 |

|

Renter |

56.9 |

235 |

|

Other |

8.0 |

33 |

|

No data |

0.7 |

3 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

413 |

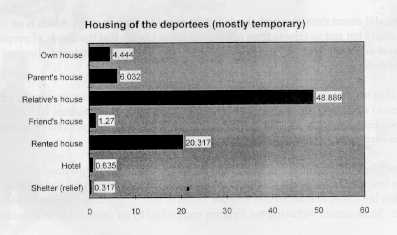

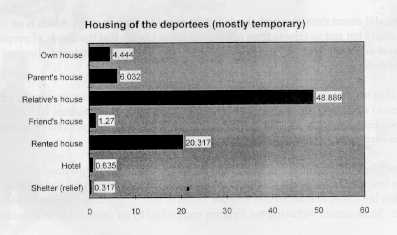

These families, who led stable lives in homes they owned or

rented, are now scattered

across Eritrean towns and living in an ephemeral environment. Aside

from a small

proportion (4.4%) who own homes in Eritrea, most of the remaining

families and

individuals have obtained temporary accommodations with their

parents (6.0%) relatives

(48.9%) or friends (1.3%). Some have acquired one or two rooms in

the highly congested

rental properties in the Asmara. A few are staying in hotels or

shelters. As can be seen in

the graph below, the housing pattern is listed from the most to the

least stable types.

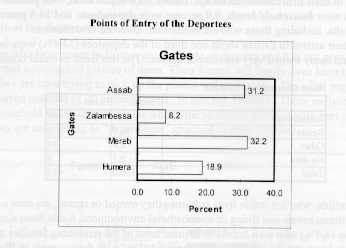

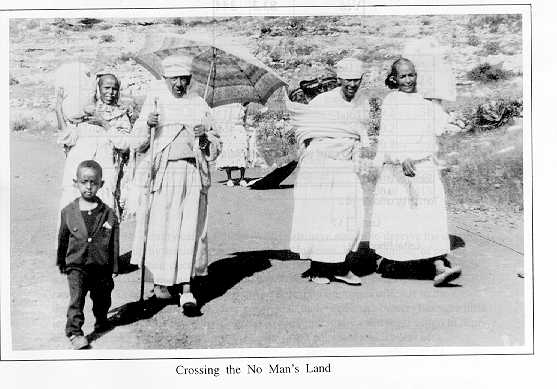

The Gates

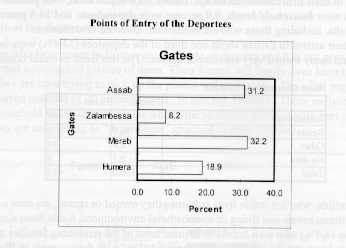

The deportees came into Eritrea through four gates that are

spread across the

entire 1000 kilometer (620 mile) wide border: Assab, Zalambessa,

Mereb, Humera.

Recently, Assab has become the principal if not the only point of

entry, in contrast to the

earlier situation when people were coming through all four routes.

The rationale for this changing picture is that the Assab route is

the most difficult for the

deportees and for their families, particularly the children. If the

deportations are intended to

be a form of punishment or humiliation then the Assab route achieves

that purpose quite

well. It is also the least public route.

The Danakil desert through which the deportees travel for days to

get to Assab is so

forbiddingly hot and so remote from major population centers that

thousands of people can

travel in fleets of as many as twenty or twenty five busses without

being observed by the

international press.

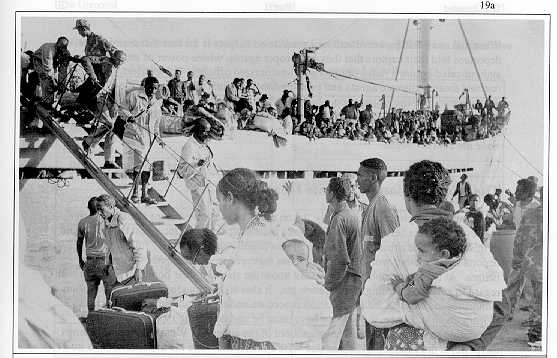

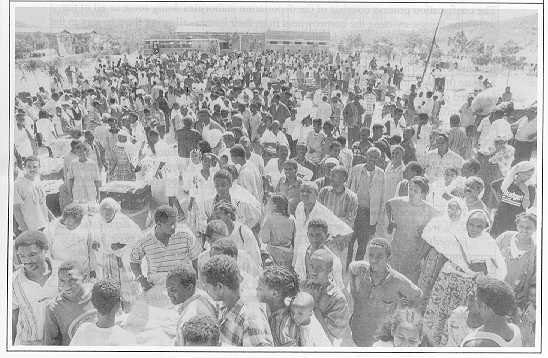

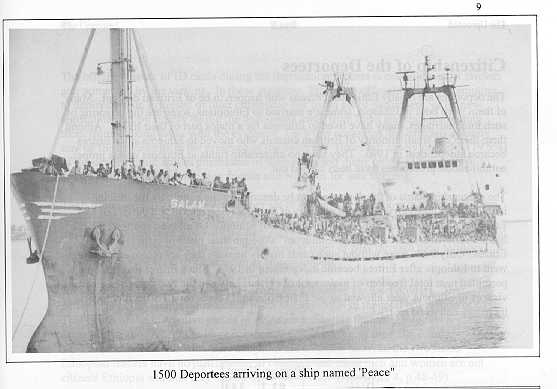

When they have completed this difficult trip, they have another

arduous journey on the

platform of open freighters lasting between 24 and 36 hours. The

freighters take them from

one Eritrean port to another i.e. from Assab to Massawa. They arrive

in Massawa in

With each arriving group, a few individuals are taken by

ambulance to a hospital to

receive first aid. Some of the children are exposed to the burning

sun for so long that their

skin blisters or is infected and they are forced to remain standing

for a major part of the

trip. Some cannot withstand the freighter trip and ~o by air from

Assab to Asmara.

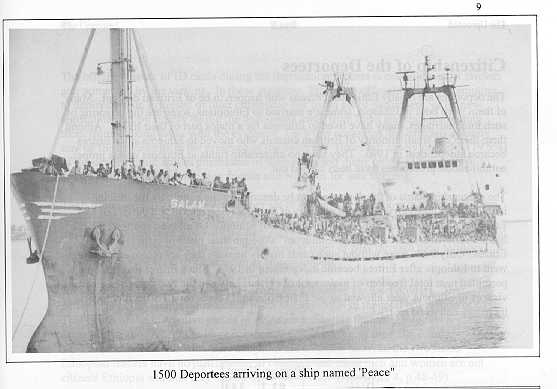

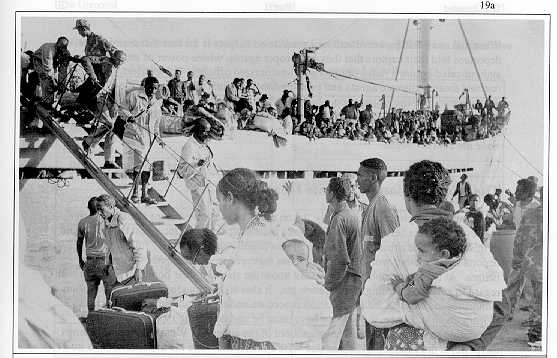

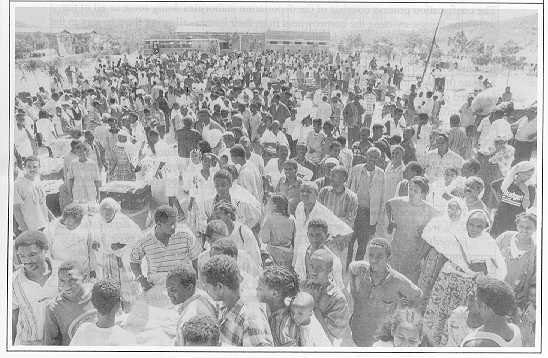

1500 Deportees arriving on a ship named

"Peace"

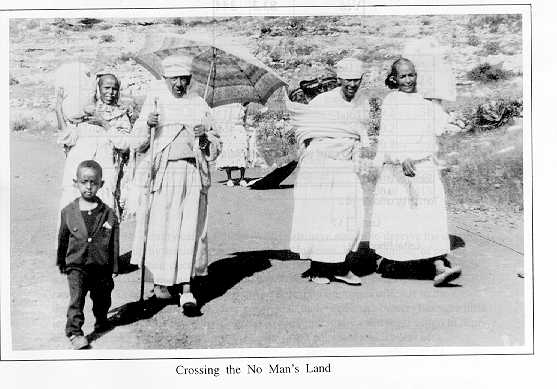

Deported Nuns and a small boy Crossing the No Man's

Land

Citizenship of the Deportees

The deportees are mostly Ethiopian citizens who happen to be

of Eritrean descent.

Many of them were born in Ethiopia, some are married to Ethiopians,

some are the

offspring of such intermarriages, many have lived in Ethiopia for a

major part of their lives.

Among them there is a small minority of Eritrean citizens who moved

to Ethiopia since

Eritrea became independent in 1993. They have no citizenship rights

in Ethiopia unless

proper naturalization procedures have been carried out.

The citizenship status of the deportees can be described quite

simply by the official

identity cards they carry. The vast majority of the deportees,

83.3%, are bearers of

Ethiopian identification cards issued to citizens of Ethiopia. Of

all the deportees, 70.7% had

ID cards marked "Citizenship: Ethiopian" although their place of

birth is often in Eritrea.

Only 9.5% were without such cards mainly because they are recent

émigrés

who went to Ethiopia after Eritrea became independent in 1993. Since

Eritrea and Ethiopia

permitted near total freedom of movement of citizens between the two

countries, Eritrean

visitors in Ethiopia were allowed to use their Eritrean ID cards for

all official purposes,

including entry and exit.

Ethiopian ID card

| |

Percent |

Count |

|

Yes |

83.3 |

344 |

|

No ID |

9.5 |

39 |

|

Not relevant |

|

|

|

Overage |

0.7 |

3 |

|

Underage |

5.6 |

23 |

|

Visitor |

0.2 |

1 |

|

No data |

0.7 |

3 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

413 |

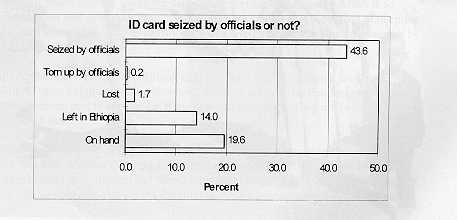

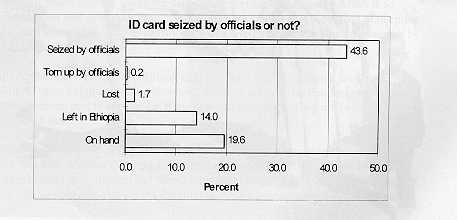

The official seizure of ID cards during the deportation process

is one of the most

lawless acts witnessed by the victims. In these instances, Ethiopian

off1cialdom was

attempting to deprive ethnic Eritreans of their citizenship not by

an act of parliament, or by

new legislation, but by simply taking the documents away from them

and thus preventing

them from walking away with the evidence. On a few occasions, the

off1cials actually tore

up the documents in the presence of the deportee. However, nearly

one fifth (19.6%) of the

deportees are still in possession of their cards and many others

(14%) have left them in

Ethiopia with Ethiopian friends and relatives for safe keeping.

Their Ethiopian passports are yet another set of documents that

show that many of

them were full-fledged citizens of Ethiopia, not merely legal

residents. A passport is an

international document governed by customary international law. It

is an off1cial request by

one state to other States to allow its citizens to enter or pass

through their territory. It is as

clear an indication of citizenship as any document.

No fewer than 21.8 percent of the deportees are Ethiopian

passport holders. That

percentage in the sample corresponds to 1500 individuals in the

total population of 6880.

That is one of the instructive pieces of evidence indicating that

the Ethiopian regime is

deporting its own citizens in large numbers, purely because of their

ethnic origin. They are

innocent individuals who were caught in the crossfire between the

two states. Ethiopian

leaders have no justification in claiming that these men and women

are not citizens Ethiopia

and that they can be deported at will. (Appendix 4)

Passport holder

| |

Percent |

Count |

|

Yes |

21.8 |

90 |

|

No |

78.0 |

322 |

|

Visitor |

0.2 |

1 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

413 |

Passport Seized

| |

Percent |

Count |

|

Seized |

5.8 |

24 |

|

On hand |

5.6 |

23 |

|

Left in Ethiopia |

9.2 |

38 |

|

Lost |

0.2 |

1 |

|

Other |

0.2 |

1 |

|

Not relevant |

|

|

|

No Passport |

78.9 |

326 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

413 |

Here, as with the identity cards, Ethiopian officials have sought

to deprive the

deportees of their citizenship by seizing their documents. However,

a large number of

people (14.8%) still have their documents with them or have left

them with Ethiopian

friends and relatives. These can serve as evidence of their

citizenship rights. The fact that

so many of the identity cards or passports were seized by Ethiopian

officials in the

deportation procedure and were never returned to their legitimate

owners has very little

legal merit. Unless the Ethiopian State takes constitutionally valid

legal action to deprive

ethnic Eritreans of their citizenship, the seizures are pointless

and lawless acts.

There are references to those identity cards and passports in

many other documents,

which the deportees possess. The evidence of their citizenship

cannot be so easily rubbed

out.

The Rights of Ethnic Eritreans in Ethiopia

According to the current Ethiopian constitution, no Ethiopian

can be deprived of

his citizenship or deported out of the country under any

circumstances. If a citizen commits

a crime, he or she can be punished in other legally instituted ways

but not by deportation.

In Article 33 (1), the present (1995) constitution of Ethiopia

states that "no Ethiopian may

be deprived of his (her) citizenship without his (her) consent."

On the occasion of the 1993 referendum, one state, Ethiopia,

became two states,

Ethiopia and Eritrea. At that point in history, Eritrea permitted

dual citizenship, Ethiopia did

not. Ethiopia then had an obligation to give ethnic Eritreans a

choice: they should have been

asked to give up one or the other nationality. The Ethiopian

parliament under the leadership

of H.E. Tamrat Laine, who was then Prime Minister, debated the issue

and came to the

conclusion that the matter should be investigated. 16

Other nations faced with a similar dilemma have found a far more

humane solution

than the one Ethiopia has adopted. In 1975, this writer was living

in Holland and witnessed

an event that is relevant to our discourse. In that year, Suriname

gained its independence

from the Netherlands. The Surinamese were then given a choice of

retaining their Dutch

citizenship or taking up Surinamese citizenship. Thousands of

Surinamese who chose to be

Dutch citizens arrived in Holland by ship and were then taken by

busses to many

communities across the Netherlands, who welcomed them to their new

homes. That is how

one civilized, democratic society dealt with this problem.

It is our understanding that Ethiopian officialdom is planning to

invoke an article in

Emperor Haile Sellassie's 1931 constitution, which states that any

Ethiopian who takes up

another citizenship automatically forfeits his or her Ethiopian

citizenship. 17

This thinking is, however, not valid because that constitution has

been superceded by two

others, in 1955 and 1995, neither of which preserves this particular

article. Furthermore,

the idea that ethnic Eritreans who voted in the referendum by which

Eritrea became an

independent state, and the likelihood that they voted for Eritrean

independence and were

issued Eritrean identity cards, constitutes an assumption of

Eritrean citizenship and, ipso

facto, a renunciation of Ethiopian citizenship has no constitutional

validity.

Why did the Ethiopian parliament under Tamrat Laine leave the

question of Eritrean

citizenship after the referendum undecided? It seems clear that the

matter was left in an

ambiguous state for very good political reasons. In those years,

EPRDF -- the coalition

party that is in power to day in Ethiopia -- was fighting for its

own political life. It was

engaged in an election campaign that was to determine the character

of the new Ethiopia and

the role that the victorious forces of the Tigray People's

Liberation Front and their allies in

the EPRDF would play in the emergent state.

The coalition party mobilized the ethnic Eritrean population of

Ethiopia to vote for it.

Eritreans responded with great enthusiasm because their own fate was

tied to that of

EPRDF - the party that was most likely to protect their rights as

Ethiopian citizens. They

were issued voting cards and they voted in great numbers. Some of

them ran for local

office and were elected as members of the District (Wereda)

assemblies. Some were elected

to the professional committees of the EPRDF. Many of them

contributed financially to

ensure the survival and ultimate victory of the party. Some even

served as election officers.

All that happened in 1996, a full three years after the Eritrean

referendum of l 993. Ethnic

Eritreans in Ethiopia cannot take part in such critical political

activities in 1996 if they had,

in fact lost their citizenship in 1993.

In regard to the political contributions of the deported

population to the election

campaign of EPRDF, our data reveal that 6.8% of them were party

members, 19.6% made

financial contributions to the party's campaign funds, and 45.2%

voted to elect the party.

That is a very sizable voting block, which any politician would love

to win over.

Even before these political developments of the mid 1990's,

ethnic Eritreans in

Ethiopia played an important role in stabilizing the government of

Ethiopia after the three

key liberation fronts in the region brought down the communist

military junta that had ruled

the country in the previous decades. The liberation fronts in

question were EPLF (Eritrean

Peoples Liberation Front) in Eritrea and TPLF (Tigray People's

Liberation Front), EPDM

(Ethiopian People's Democratic Movement, predominantly Amhara) and

OLF (the Oromo

Liberation Front) in Ethiopia. These fronts collaborated in bringing

down the heavily armed

junta, overburdened with 12 billion US dollars worth of Russian

military hard ware it had

accumulated over the years (1975-91). In 1991, Eritrean mechanized

brigades marched all

the way up to Addis Ababa side by side with the Ethiopian liberation

forces and used their

highly efficient heavy artillery units to break down the resistance

of the junta and its

massive army. They helped to bring down the dictator Mengistu

Hailemariam and to install

P.M. Melles Zenawi and his coalition party in the positions they now

occupy.

The months and years that followed the collapse of the junta were

very precarious.

There were huge numbers of Ethiopian soldiers who had suddenly been

cut adrift. Unruly

bands of soldiers were using their rifles to "live off the land."

Ethiopia was in a liminal

state or an inter-regnum: which, in Latin, means that "one

government was out and the

other one was not yet in" -- a kind of temporal no-man's land. In

that transitional state, the

TPLF armed many ethnic Eritreans and got them to serve as members of

the "Pacification

and Stabilization Force," referred to in Amharic as selamnna

merregagat. Their job was to

use the arms that were given to them to fend off any attempt to

destabilize the newly

installed government. Our survey shows that 7% of the deportees

served in this force.

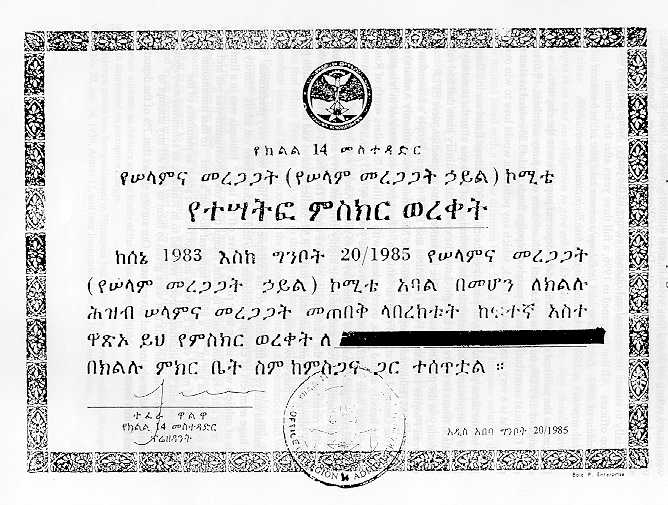

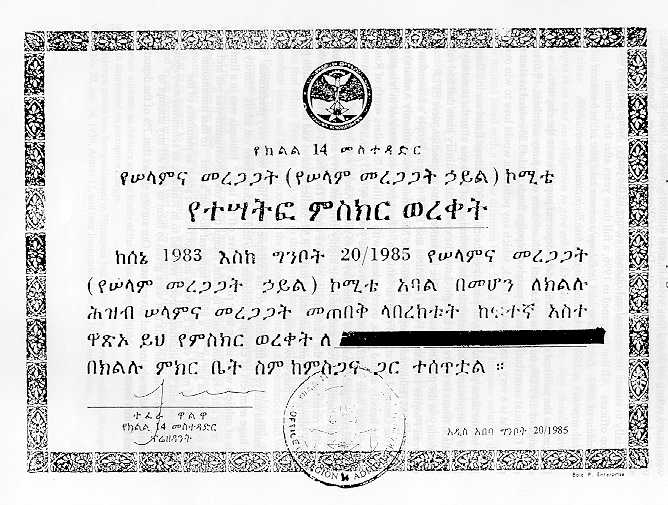

A certificate issued to an ethnic Eritrean

citizen of Ethiopia, honoring him for his "great

contribution" to the Pacification and Stabilization Campaign. He

served in that capacity

from 1991 to 1993 (1983 to 1985, Ethiopian calendar). He is one of

481 deportees in the

population we surveyed, who helped to stabilize Ethiopia after the

liberation of 1991. Most

of them have such certificates or an ID card marked "one

Kalashnikov" issued for the

pacification campaign.

Seven years later, the home of those same ethnic Eritreans who

helped to stabilize the

country, were raided by TPLF security officers and they were

deported out of the country

on the pretext that they were "foreigners" "enemy aliens" and a

"security risk." This is one

of the many callous contradictions that prevail in Ethiopian

political life to day, suggesting

that the country is in a state of deep denial. Ethiopian leaders

have turned vehemently

against those who supported and defended them in their hour of need.

Ethnic politics and its social consequences

The new Ethiopia did not only create an ethnic federation but

she also wages its

political wars along ethnic lines. The newly crafted "Ethnic

federalism" is one of the most

dangerous experiments with ethnic politics, which has so far

surfaced in the African

continent and probably has no parallels in Africa. The Ethiopian

ethnic states were created

with humane intentions, but the consequences have been unfortunate.

There are, for

instance, explosive tendencies in the relationship of the current

regime of Ethiopia with all

those ethnic liberation fronts or political parties of the Oromo

(OLF), the Ogaden Somali

(ONLF), the Afar (ALF), and the Amhara (AAPO). These are some of the

indigenous

fronts and parties that were violently suppressed by the EPRI)F

coalition and supplanted by

ethnic political parties created or nurtured by the regime.

We need to pay attention to Ethiopian ethnic politics in this

paper because it has had a

major impact on the present crisis and the deportation process.

Ethnicity as a social factor

impinges on the conduct of those who are doing the rounding up, the

jailing, dispossessing

and the deporting of ethnic Eritreans from Ethiopia. As such it is

eminently relevant to the

issues human rights under discussion.

The campaign against Eritrean civilians in Ethiopia is ethnic at

its source and it is ethnic

in its objective, in spite of the fact that it attempts to wear the

mantle of "national

sovereignty or security." It is partly motivated by the need to

humiliate Eritreans, in

response to a feeling that Tigrayans, particularly the people of

Eastern Tigrai, are viewed

contemptuously by Eritreans. That is the agenda behind many other

agendas. It is

discussed in the local press, in vernaculars, but not in the

international press, in English.

Whether the leaders choose to speak about it or not, the O.A.U.

"elders" who are mediating

the conflict cannot ignore it. No mediation can succeed unless it

can uncover the "hidden

agenda" of either or both parties and , as elders in Africa, who are

daily engaged in

mediation work and peace making, know so well.

The role of ethnic politics in the deportation drama: the

players

There are many characters that are key players in the

deportation campaign. These

are the faceless informer, the familiar informer, the raider, the

'deporter,' the jailer and the

bus guard. Each one of these players will be discussed in different

parts of this paper.

The faceless informer

An important, but obscure, player in the current deportation

campaign is the

faceless informer, who makes it his business to hunt out Eritreans

and report them to the

authorities. He, more than any one else, is responsible for the

state of terror in which the

Eritrean community in Ethiopia finds itself today. So great is the

anxiety generated by this

faceless threat, that many Eritreans wait in their homes ƒ with

suitcases packed

ƒ for the day when the ax will fall. Many sleep on the floor

after having sold all their

furniture and their beds. Some try to leave the country voluntarily,

after putting their affairs

in order, but very complex bureaucratic restrictions are put in

their way. They will be

allowed to leave when the regime says it is time. They will leave on

its terms, not theirs.

We have much descriptive information but little statistical data

on the paid informers.

Their existence is known to the deportees, because they often bring

the official raiders to

the home of an Eritrean, deliver their victims to the security

officers and then make a hasty

retreat. They are mercenaries who are paid by the security apparatus

for their services.

They do not hesitate to give false information about their victims

in order to drum up

business for themselves.

The familiar informer

Aside from the faceless informer, who works covertly, the

other types of

informers are well known to their victims. The most common type is a

neighbor, who has

been close enough to his victims socially, to be able to describe

their life histories, political

affiliation and social network: 20% of the deportees report that it

was a neighbor who

reported them to the security organization and recommended that they

be thrown out of the

country.

It is important to stress, however, that not all neighbors are

informers. Many are

disturbed by the deportations. They look after the children and

property left behind by the

deportees and offer their help in many small and understated ways,

such as relaying

information to the deported parents about the plight of their

children, their homes and their

properties. Necessarily, this role of the good Samaritan must remain

understated, so as not

to provoke the ire of the regime.

Others, however, turn violently against their neighbors and

pressure their victims to

sell their homes, cars and possessions to them at dirt-cheap prices.

They are motivated by

undisguised greed. One Eritrean woman was asked to sell a television

set worth 10,000

Birr (US$ 1500) for about 400 Birr ($50). She picked up the set,

dropped it on the cement

floor, smashed the tube into bits, and declared "There, you can now

pick up the pieces for

free!" The conduct of these neighbors, turned into informers and

scavengers, is a source of

much anger and resentment among the deportees.

In the world of informers, the Judas factor is most apparent in

the case of co-workers

(6.8%) and friends (4.1 %) who turn upon their Eritrean colleagues.

These are people

whom Eritreans respected and trusted, people who had, for years,

shared in their joys

and sorrows, their weddings and funerals. Among these there is a

small number (0.7%)

who were the childhood friends of the deportees.

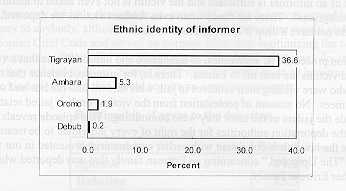

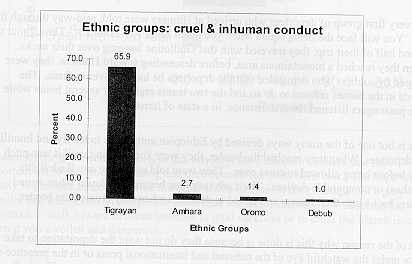

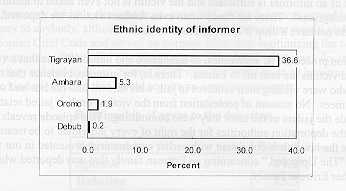

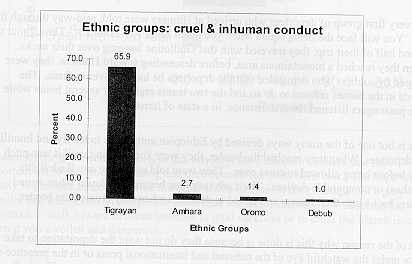

Ethnic Identity of Informers

In the earliest stages of the Ethiopian-Eritrean conflict,

P.M. Melles Zenawi

declared that there is nothing ethnic about the war that his regime

declared on Eritrea. He

said that his government is not "anti-people" but opposed to the

regime now in power in

Eritrea. (Appendix 4) That has now turned

out to be far

from the truth. Evidence is emerging that Tigrayans are at the

forefront of the deportation

war, which is specifically aimed against ethnic Eritreans.

Nevertheless, it is obviously not

an exclusively Tigrayan campaign because it encompasses the three

major ethnic groups in

the country.

The ethnic campaign backfires

In all this, the position of the Oromo is most interesting.

They are, by far, the

biggest ethnic group in Ethiopia (some 18.8 million souls, as

opposed to 3.1 million

Tigrayans, as per the 1994 census). Oromo are obviously not taking

part, whole-heartedly,

in the deportation campaign. Their movement was crushed by the

Tigrayan army in the

early 1990's. Their national liberation front (OLF) was barred from

taking part in national

politics and their leaders were driven to exile. They are,

nonetheless, feared because they

can be expected to play a dominant role in any open democratic

polity that might be

established in the country. The Oromo are clearly not enthralled

with the ethnic hate

campaign launched by Tigrayan leaders and have delivered a coup de

grace of their own

invention. They have, on occasion, "deported" Tigrayans from their

territory (Oromia)

along with ethnic Eritreans, with the explanation that they cannot

tell the two groups apart.

They say that both speak the same unintelligible language, Tigrinya,

and they are both

known to them as "Tigre."

Do deportations have legal authority? Who authorizes them?

In many cases, police officers were involved in carrying out

the deportation

procedure. However, their role in this ethnic cleansing campaign

should not be overstated.

Many a police station chief has stated that the Eritreans brought to

him cannot be detained

unless they have violated laws and that merely being an Eritrean is

insufficient ground for

imprisonment. This is amazing law-abiding behavior in the midst of

all the turmoil and

lawlessness surrounding the deportations.

By contrast, all the other types of off1cers who have played a

role in the deportations

are most unlikely to raise questions about such fine points of the

law as guilt and

innocence. The dominant party, EPRDF, has declared war on Eritreans

and they are merely

carrying out the mandate given to them by the party. Local (Kebele)

administrators are

EPRDF party operatives as are the security and army officers. These

require no justification

to jail or deport an Eritrean, so long as the person's Eritrean

descent is established. Often,

the statement of an informer is suff1cient and the victim is not

even asked to identify his

own ethnic background. There are times when even Amhara victims are

deported, though

they do not have a drop if Eritrean blood in them.

The deportation procedure is, sometimes so haphazard and

indiscriminate that a variety

of unintended victims are sent off to Eritrea. There is, for

instance, evidence that two

individuals who were visiting their relatives in jail, were thrown

into the bus and sent off

with the detainees. No amount of protestation from the victims or

their jailed relatives could

persuade the jailers of the error they were committing. This episode

reveals the disregard of

the deportation authorities for the right of every individual to be

treated as "a person before

the law." It is consistent with earlier case material presented in

our first report, titled "The

Uprooted," concerning an Eritrean family that was deported while

visiting another Eritrean

family.

Violation of Ethiopian law and constitution

Intermarriage between Eritrean and Ethiopian citizens has

become a major source

problems in the present deportation campaigns. A full 12% of the

deportees are Eritreans

married to Ethiopians who have been forced to leave their spouses

and children behind.

Surprisingly, the deportation authorities also violate Ethiopian law

by sometimes deporting

Ethiopians married to Eritreans. Article 33 (1) of the 1995

constitution states

Marriage to a non-Ethiopian does not invalidate his (her)

Ethiopian citizenship.

In practice, however, it does. The broad-brush accusation leveled

against such mixed

marriages is that they are "Sha'biya (EPLF) families." In such

situations, both husband and

wife are sometimes deported. Each of these couples who are, thus,

deported is a double

violation of Ethiopian law and, in the case of the indigenous

spouse, even the shaky legal

edifice that has been built to legitimize the deportations is

irrelevant.

The power of attorney exercise: prelude to confiscation

Nothing demonstrates more effectively the lawlessness that is

creeping into

Ethiopia than the manner that the property of the deportees is being

treated. Ethiopian

authorities insist that they do not "confiscate" property and that

the homes and businesses

of the deportees are simply being kept under the control of the

Ethiopian government, until

such time as the law can properly dispose of them. To assure the

deportees that this

disposal of property will be legally conducted, they are asked to

write a power of attorney

document authorizing a person of their choosing to represent them in

the disposal of the

properties.

The fact is, however, that the procedure is quite vacuous. The

power of attorney

document they were asked to prepare was but a note on a blank sheet

of paper not properly

notarized by a court of law. In most cases the designated agents

were not even asked to

give their consent. They were authorized in absentia. They may not

even be aware of the

responsibility that was being placed upon them and could easily turn

down the offer. 18

Under these very dubious circumstances, only 50¯/0 of the

deportees agreed to

give power of attorney to anybody, although they believed that the

procedure was in

violation of the Ethiopian Civil Code and served no purpose other

than legitimizing the

confiscation of their properties. Others (7.7%) did not prepare the

power of attorney

document because they refused to do so. Some (24%) were not asked to

do so because

they did not have the kind of property that would require an agent

to dispose of it.

Relationship of agent to the deportee

|

Relationship |

Percent |

|

Spouse |

24.2 |

|

Relative |

13.3 |

|

Co-worker |

2.4 |

|

Friend |

4.6 |

|

Neighbor |

4.6 |

|

Other |

0.9 |

|

Total (of those who gave power of attorney in detention)

|

50.0 |

Those who did write the document had difficulty finding an agent

while they were in

custody. Unable to think of an appropriate person, many of the

deportees designated their

wives (24%) or relatives ( 11 %) as their agents, only to find that

they too were deported

soon after them, leaving their properties completely abandoned

without a caretaker. About

one third of the respondents (33.5%) felt that they had given the

power of attorney to a

hastily chosen person under duress.

The dispossessed collecting what is left of all their earthly belongings

What makes all this power of attorney exercise so suspect is the

fact that many of the

deportees told their captors that they had proper agents, whose

power of attorney was

authenticated before a judge or other court-authorized off1cers.

Their jailers, however,

rejected these legitimate agents and pressured their victims to go

through the exercise,

insisting that the slips of paper on which they had written the

power of attorney instructions

would be legalized at some later stage. There is no indication that

any of the agents so

designated have been given such properly authorized documents, at

any time since the

conflict began.

The Confiscation of Private Homes

The home of a deportee is commonly "taken over" by the

Government of

Ethiopia. However, there are several factors that make it difficult

for us to document the

full extent of this practice statistically. Our research was

conducted immediately following

deportations. In other words, each group was surveyed or interviewed

as it arrived in

Eritrea. At that time, most people did not know the status of their

homes in Ethiopia with

regard to evictions, sealing, confiscation etc. It also takes some

time for the deportation

authorities to complete the confiscation procedure and even more

time for the deportees to

learn about it. To permit an adequate assessment of the situation,

the data we have must be

updated in the months following deportation. What we present here,

therefore, is the

situation of homes that were confiscated while the deportation was

in progress or very soon

thereafter.

The confiscation process consists of the deportation authorities

doing some or all of the

following things: evicting the homeowners from their homes, allowing

them to stay in the

servant quarters -- if part of the family remains behind, after the

household head is deported

-- preventing the family from getting access to the contents of the

house, handing over the

house to officials to live in, and finally "sealing" the house. The

act of "sealing" a house

(masheg in Amharic) means that the doors are locked and a piece of

paper is pasted on the

main door stating that the property is under Government control.

Since the authorities do

not prepare inventories of the sealed properties or issue a receipt

to the deportee, there is

nothing to prevent the deportation personnel from entering the house

through one of the

unsealed entrances and helping themselves to its contents. The

procedure invites corruption

and vandalism. Amazingly, the dictatorial military junta of the

pervious decades used to

prepare an inventory and issue a receipt before confiscating a

house, but to day's

Democratic Federal Republic of Ethiopia does not.

The evidence shows that, of all the houses owned by the Eritrean

deportees 27% were

immediately sealed by the authorities. during the deportation

procedure or soon thereafter.

These homeowners who have lost their houses constitute 9. 7% of the

sample, or an

estimated 646 homeowners out of the total population of 6880

households. Although they

have no receipts for their confiscated properties, many of the

families have documents

showing the value of their estates and the manner they were

acquired. A few of them have

detailed inventories.

Data on Houses Owned by Deportees and their Confiscation by

Ethiopian

Authorities

Owned houses sealed

| |

% |

Count |

|

Owned house sealed |

9.4 |

39 |

|

Occupied by remaining family* |

29.3 |

121 |

|

Don't know state of house |

24.7 |

102 |

|

Not relevant _ |

|

|

|

Renters whose house not sealed but taken over |

24.9 |

103 |

|

Dependent |

9.9 |

41 |

|

Visitor to Ethiopia |

0.2 |

1 |

|

No data |

1.4 |

6 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

413 |

Agent ordered to sell

| |

% |

Count |

|

Agent ordered to sell |

7.0 |

29 |

|

Not ordered to sell |

15.3 |

63 |

|

Do not know |

8.7 |

36 |

|

Not relevant |

|

|

|

Renters & dependents |

66.8 |

276 |

|

No data |

2.2 |

9 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

413 |

*Rented & owned mixed

Months given to sell house

|

Owners given X months to sell |

% |

Count |

|

One month |

4.4 |

18 |

|

Two months |

1.5 |

6 |

|

Three months |

0.2 |

1 |

|

Don't know |

9.9 |

41 |

|

Not relevant |

|

|

|

Not ordered to sell |

3.2 |

13 |

|

Renters & dependents |

66.8 |

276 |

|

No data |

14.0 |

58 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

413 |

Rest of family deported before deadline

| |

% |

Count |

|

Deported before deadline |

3.4 |

14 |

|

Not deported before deadline |

11.9 |

49 |

|

Don't know |

9.0 |

37 |

|

Not relevant |

|

|

|

Not ordered to sell |

66.8 |

276 |

|

Renters & dependents |

8.7 |

36 |

|

No data |

0.2 |

1 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

413 |

Sale of house

| |

% |

Count |

|

Agent sold house |

0.5 |

1 |

|

Agent did not sell house |

29.2 |

121 |

|

Owner not ordered to sell |

0.5 |

2 |

|

Don't know if remainingfamily ordered to sell |

0.7 |

3 |

|

Not relevant |

|

|

|

Renters and dependents |

62.8 |

260 |

|

No data |

6.3 |

26 |

|

Tatal |

100.0 |

413 |

Did owner sell his (her) house?

| |

% |

Count |

|

I sold my house |

1.7 |

7 |

|

I did not sell my house |

31.0 |

128 |

|

I was not ordered to sell and did not sell |

0.5 |

2 |

|

Not relevant |

|

|

|

Renters & dependents |

66.8 |

276 |

|

No data |

0.0 |

0 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

41 |

During the weeks that the remaining family members were in this

precarious state, they

were often ordered to sell their home if it was not already sealed.

They were given a

deadline of one to three months. Most of them were given just one

month.

What was the meaning of this deadline? How does a family sell a

home within a

month? Most families take at least a year to complete the process of

advertising, finding

buyers to offer bids, selling and authenticating the transfer

documents. Hence, the deadline

is quite ludicrous. But it becomes even more ludicrous when we

realize that the deadline

itself was not honored. In most cases, the members of the family who

remained behind

after the deportation of the household head, were themselves

deported before the deadline.

They were deported one to four weeks after the deportation of the

household head (5%).

Under these circumstances, most homeowners were reduced to having

to sell their

homes in less than four weeks. A few homeowners (5%) sold their

homes at throwaway

prices. Many had to fall back on the power of attorney procedure

made up by the

deportation authorities. Some of the victims told their captors that

the procedure was in

violation of the Ethiopian civil code and that it had no validity

whatsoever. They were told

that the government would legalize the documents subsequently.

However, we have not

found a single piece of evidence indicating that they have done so

during the six months

that have elapsed between the beginning of the deportations and the

time that we completed

this survey. Throughout that time, we have a record of only one

agent legally selling a

house on behalf of a deported family. That agent had a proper court-

authorized power of

attorney document prepared long before the deportations began. In

other words, not a

single case has turned up in our survey, showing that a house had

been sold on the basis of

the flimsy power of attorney documents prepared while the internees

were in custody.

The entire procedure, therefore, looks like a crude scheme

designed to give the

appearance of legality. It is clearly not intended to achieve the

ostensible purpose for which

the procedure was established. It is also important to realize that

the confiscation of

property we have discussed here concerns private houses only. It is

consistent with our

objective of studying only phenomena that are widely distributed in

the population. Our

study does not deal with the properties owned by Eritrean

businesses, entrepreneurs,

banks, corporations, industrial plants and the very large

association of Eritrean truck

owners that accounted for between 80 and 90% of the truck haulage in

Ethiopia. A11 that

will be the object of later studies. It has, in large measure, also

been documented in the

ERREC census and data base.

Vestiges of the rule of law

In all the activities described above, there is a measure of

thinly disguised

lawlessness. Surprisingly, however, there is one branch of the law-

enforcement

community that has exhibited some hesitation about this lawless

conduct. As indicated

earlier, the police force has not entirely abandoned its

professional ethics. To the extent that

they are able to resist the pressures of the security apparatus,

they do, sometimes, insist

that even Eritreans are protected by the law. For instance, many a

police station chief

insisted that the detainees must have broken the law in order to be

taken into custody and

that merely being an Eritrean is not adequate ground for

imprisonment. Hence, the

deportation authorities had to improvise to find some place in which

to keep their victims.

They have used a whole assortment of buildings such as garages,

schools, and private

homes as detention centers. In one case, in Mekele, they were unable

to find an appropriate

place of detention. They then simply smashed the doors of one house

that had been vacated

by a previous deportee -- a teacher named Memhir Hadgu -- and used

it as a makeshift

prison. The reader should recall that the rationale given for

seizing and sealing the home of

an Eritrean deportee and its contents was for 'safe keeping' until

it could be disposed of

legally, with the aid of the designated agent. Instances such as

this make a mockery of that

procedure.

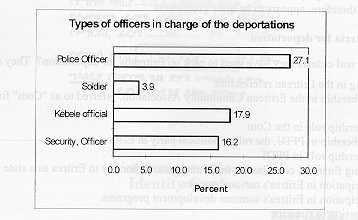

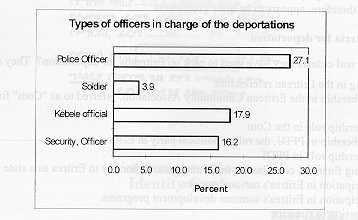

Types of officers in charge of the deportations

Of all the off1cials who were responsible for carrying out the

deportations, 27.1% were

police officers. Most of the others, such as the local Kebele

administrators (17.9%) or the

security (16.2%) and army officers (3.9%) were either EPRDF party

operatives or had

direct links with the ruling party which had declared war on Eritrea

and Eritreans. As far as

they were concerned, all Eritreans pose a security threat to the

country. They are, in the

words of party officials, "Shabiya's fifth column" inside Ethiopia.

(Appendix 4, paragraph 13). They are

thought to be using their

considerable wealth to supply the Eritrean army with money,

resources, and information.

They are said to be indirectly responsible for the bombing of

Tigrayan towns (an event that

took place after the Ethiopian Air Force bombed Asmara).

Absence of judicial authority in the deportations

It is not diff1cult to establish that the judicial arm of the

Ethiopian government is

playing no significant role in the deportations. With the exception

of the police off1cers, the

deportation personnel has no reason to be particularly knowledgeable

about the national

laws of Ethiopia or to be aware that these laws are in any way

applicable to the deportees.

Furthermore, all the personnel who directly confront the deportees

at every stage of the

deportation process and about whom we have evidence appear to be

largely unaware of the

international laws governing the position of civilians in wars

between states.

Alleged Crimes Committed against Ethiopian National Security

In uprooting a whole segment of Ethiopian society from their

homes,

neighborhoods, jobs, and businesses, the Government of Ethiopia

claims that they did so

for reasons of national security. We have not found any deportees

who were accused of

engaging in espionage, sabotage or any other activities that

constitute a threat to the

Ethiopian State. Indeed, if they were allegedly engaged in such

activities they would be

jailed, not deported. That has been the pattern of official

Ethiopian action to date. There are

many Eritreans who have been put in prison for far lesser alleged

offenses than espionage

or sabotage. From the perspective of the deported population, the

national security

justification, therefore, appears to be quite groundless.

The real criteria for deportation

What are the real criteria they have used to pick up

Eritreans for deportation?

They are:

- Voting in the Eritrean referendum

- Membership in the Eritrean Community Association, referred to as

"Com" for

short

- Leadership role in the Com

- Membership in PFDJ, the ruling political party in Eritrea

- Leadership role in PFDJ

- Making financial contribution to Eritrean associations or to

Eritrea as a state

- Participation in Eritrea's national service

- Participation in Eritrea's summer development programs

- Possession of firearms

l 0 Visits to Eritrea

The residual criterion, invoked when all the above criteria

fail to incriminate

After applying the above ten criteria, if the official cannot

find fault with the

prospective deportee, he or she then asks the two or three questions

which are the residual

but critical questions.

- Place of birth

- Father's place of birth

- Grandfather's place of birth

If it turns out that the individual was born in Ethiopia, then

the interrogator inquires

where his or her father was born. If that produces the right

response, i.e. Eritrea, the

off1cial declares "Well then, you are going to go back to your

country!" or words to that

effect. If not the interrogator proceeds to ask about the

grandfather's place of birth.

In short, the criterion that is ultimately used to expel

Eritreans is an ethnic criterion.

That criterion is applied whether the individual is an Ethiopian or

Eritrean citizen.

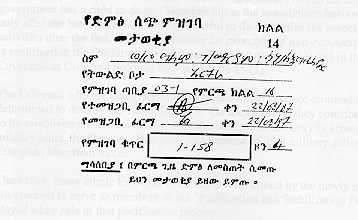

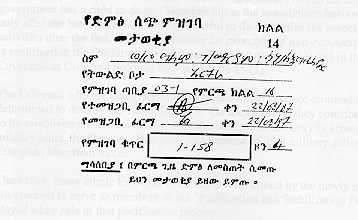

Voter Registration

Identity Card

Zone (Killil)

14

Name: Alem G/Mariam Sahlezghi

Place of Birth: Eritrea

Voting Station: 03-1 Voting Region 16

Signature of Voter Date 22/08/87*

Signature of Registrar Date 22/08/87

Registration Number 1-158

District 4

Reminder: When you come to cast your vote bring this identity

card

* The year, 1987, is according to the Ethiopian

calendar and corresponds to 1996 Gregorian Calendar, the time when

the present leadership of Ethiopia was elected.

The paradox is that each one of the ten activities now judged to

be incriminating

evidence by the Ethiopian regime were legally permitted and

politically encouraged until the

outbreak of hostilities in May 1998. Throughout the post-liberation

years (1991-1998)

there were no laws prohibiting those activities. If it wishes to ban

the associations, the

government has a right to do so. Membership in the associations

becomes an offence only

after the ban is in effect. It is not lawful to de-legitimize the

associations and activities after

the fact. Doing so violates the principle of non-retroactivity of

law, which is a basic

premise the Declaration of Human Rights, Article 11 (2) and in the

International Covenant

on Civil and Political Rights, Article 15 (1).

The Eritreans who are being deported in huge numbers are not

criminals who were

determined to destroy the Ethiopian state. On the contrary, they

contributed significantly to

its establishment as a new state, after the collapse of the heavily

armed communist military

junta, the Dergue. That junta fell because of joint military action

by Eritrean and Ethiopian

liberation forces, who received much support from the civilian

ethnic Eritrean population in

Ethiopia.

Thereafter, many ethnic Eritreans in Ethiopia were armed by the

newly established

government to serve as members of the "Pacification and

Stabilization Force." They played

a key role in that pacification process.

The coalition party, the EPRDF, that came to power as the ruling

party in Ethiopia was

elected to office partly because of the massive effort ethnic

Eritreans made to ensure its

success. They contributed funds to the party, they participated in

local (Kebele) assemblies

and professional associations of the party, and they voted for the

party in great numbers.

Our survey reveals the following facts:

- 7% of the deportees were active in the Pacification and

Stabilization

Campaign,

- 19% made financial contributions to the EPRDF & campaign

fund,

- 5% were members of EPRDF's professional associations,

- 45% voted to elect EPRDF and to help make it the ruling party of

Ethiopia.

It is very important to realize that the same people who were

active in the Eritrean

community association or in PFDJ were also active in the campaign to

put EPRDF in

power. That was a natural pattern of collaboration, because the two

parties, or their

predecessors, EPLF and TPLF, were allies in the wars that brought

down the junta.

It is disingenuous for the Ethiopian regime to now claim that the

population that helped

to bring it to power is a threat to its very existence. Here too,

the Judas factor is apparent.

Not only are the broad-brush accusations leveled against ethnic

Eritreans groundless, the

hostility of the regime toward that population is taking on the

character of a hate campaign

and is highly discriminatory by any standards of humanitarian law.

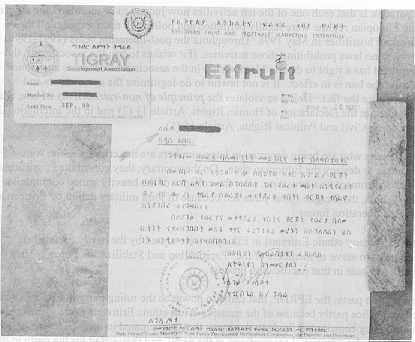

Document detailing

the retirement benefits of a deportee and a card showing that he was

making contributions to the Tigray Development Association (TDA)

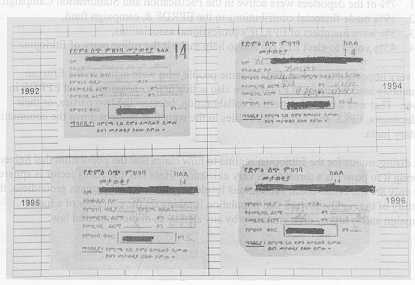

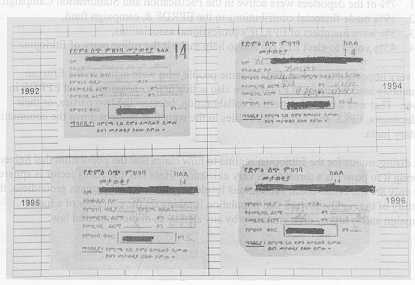

Deportees' Voting cards indicating that the bearer voted in four

different national elections: a right reserved exclusively for

citizens

Cruel and Inhuman Conduct: Break-up of Families

The area where the ethnic factor becomes blatantly clear is

in regard to marriage

and family organization. Ethiopian authorities have ruthlessly and

recklessly broken up

families in order to push the anti-Eritrean campaign to its logical

but absurd limits. If the

new order says that all Eritreans must be rooted out of Ethiopia and

if many Eritreans are

married to Ethiopians, the logical but absurd conclusion is to break

up those couples and

deport the undesirable half.

As indicated earlier, no less than 12% of the ethnic Eritrean

citizens of Ethiopia who

have been deported during the last six months were, and still are,

married to native

Ethiopians. In the great majority of those cases, the families have

been broken up and the

Eritrean member of the couple has been deported.

Another variation of this absurd procedure is to deport both

spouses and their children.

All the justification that is needed is for off1cials, informers or

neighbors to declare them to

be a "Sha'biya family."

Disruption of Eritrean families

Over and above the break up of mixed marriage families,

however, the disruption

of Eritrean family and community life generally is one of the most

inhumane aspects of the

campaign. Our data reveal that 45% of the deportees were forced to

leave their spouses

behind. Mothers have been torn away from their suckling infants,

parents from their

children, elderly parents from adult children who look after them,

disabled family members

from their care takers, monks and nuns from their monastic

communities, priests from their

congregations. The full range of atrocities committed against the

Eritrean family and

community cannot be adequately documented at this stage. We are

still gathering in-depth

qualitative data and life histories, which will be capped with a

scientific survey at a later

stage. What we have documented statistically at present gives only a

partial picture.

Children left behind by deported parents

Most parents pleaded and pleaded to be allowed to take their

underage children

with them, but their pleas fell on deaf ears. As is clearly revealed

in the following tables,

the situation of the children is pathetic: 19.2% of them were

abandoned with siblings,

neighbors, maids or with no caretakers at all. That corresponds to

3989 abandoned children

in the total population of 6880 households. It is important to note

that 1412 of those 3989

children were left with no care takers of any kind. That represents

6.8% of the households

of deportees who left their children in that state.

Separation of Spouses

| |

Percent |

Count |

|

Spouse remained in Ethiopia |

45.0 |

186 |

|

Spouse deported |

21.1 |

87 |

|

Not relevant |

|

|

|

Single adults (unmarried) |

10.7 |

44 |

|

Dependent (mostly underage) |

9.9 |

41 |

|

Spouse in Eritrea before the crisis |

2.2 |

9 |

|

Widowed or divorced |

4.1 |

17 |

|

Spouse living aborad |

1.2 |

5 |

|

Visitor |

0.2 |

1 |

|

No data |

5.6 |

23 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

413 |

Underage Children left under the care

of:

| |

Percent |

Count |

|

No Caretakers |

6.8 |

28 |

|

Siblings |

5.3 |

22 |

|

House workers |

1.0 |

4 |

|

Neighbors |

0.5 |

2 |

|

Other |

5.6 |

23 |

|

Subtotal |

19.2 |

79 |

|

Relatives |

2.7 |

11 |

|

Remaining parent: mother |

24.7 |

102 |

|

Remaining parent: father |

0.5 |

2 |

|

Not relevant: no underage children |

47.0 |

194 |

|

No data |

6.0 |

25 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

413 |

Eviction of children after deportation of

parents

| |

Percent |

Count |

|

Evicted |

7.3 |

30 |

|

Jailed |

2.4 |

10 |

|

Other atrocities |

15.0 |

62 |

|

Not Relevant |

|

|

|

No underage children |

47.2 |

195 |

|

No children evicted |

17.7 |

73 |

|

Do not know the plight of children |

1.0 |

4 |

|

No data |

9.4 |

39 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

413 |

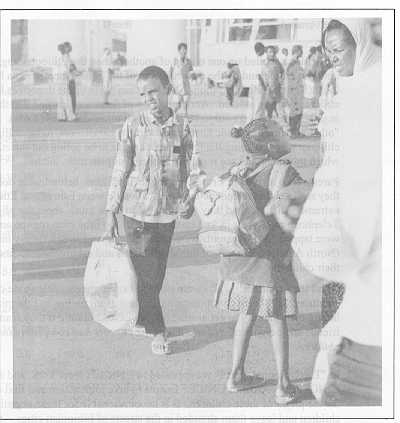

A broken

Family, no place to go

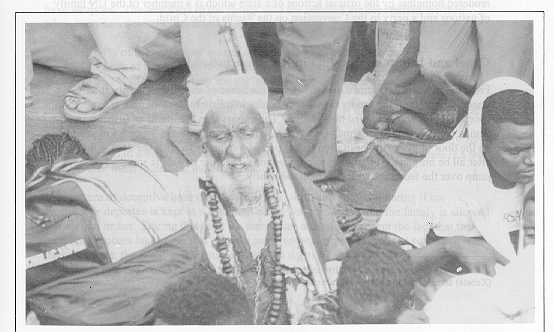

A

deported old Monk: a threat to national security?

Atrocities are piled up one on top of another when the Ethiopian

regime evicts the

children left behind by the deportees out of the homes their parents

had rented from the

local (Kebele) administration. 19

No less than 6.8 % of the deportees learned that their children

were so evicted. Another

group of deportees learned that the children were put in jail (2.4 %

) or were subjected a

variety of other atrocities (8.4 % ). In this context, "other

atrocities" include hostile acts

such as harassment, name calling and beating. The children who are

doing the harassment

appear to be acting out the ethnic hate campaign, which they hear

and see regularly in the

Ethiopian mass media.

Parents who arrived in Eritrea leaving their children behind were

deeply disturbed

when they realized that telephone-communication between Eritrea and

Ethiopia had been

made extremely difficult and they were unable to learn much about

the plight of their

children. Telephone rates were jacked up sky high by the Ethiopian

regime and telephones

lines were tapped. Many parents were reduced to having to call

family members abroad

(North America, Europe, or the Middle East) and asking them to find

out about the fate of

their children.

Of all the deportees, 12.8 % were making very expensive telephone

calls via other

countries, 12 % were communicating through third parties in

Ethiopia, and 9% were hiding

their identity to get around official eavesdropping if they manage

to get through to friends

and neighbors. A full 30% of the parents had completely lost contact

with their children.

In "The Uprooted, part I" we appealed to UMCEF, New York, and

asked them to

direct UNICEF Ethiopia and UNICEF Eritrea to take joint action and

find a humane

solution for the plight of these children. It is unconscionable for

these organizations to fail

the children and leave them stranded in the streets of Ethiopian

cities -- thousands of

children rendered homeless by the official actions of a state which

is a member of the UN

family of nations and a party to the Convention on the Rights of the

Child.

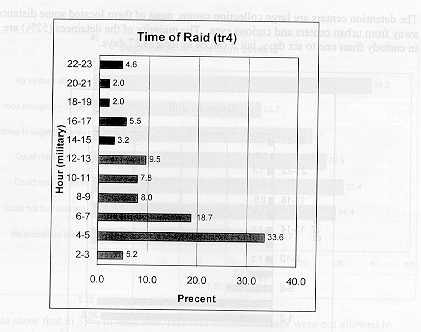

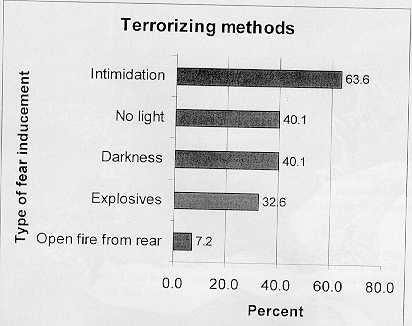

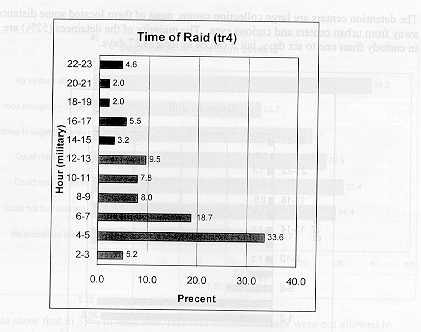

Cruel and Inhuman Conduct in the Deportation Process

From the moment that armed men break into the home of an

Eritrean family at an

ungodly hour, until the family crosses the border into Eritrea, the

deportee is exposed to

sporadic terror and sustained humiliation. The upheaval in the life

of an Eritrean family

begins when a number of armed men come, in most cases between 2 and

5 a.m., and bang

on the door or gate. Any hesitation on the part of the family to

open the door -- they could

after all be burglars -- provokes violent reaction. The door or gate

is smashed or they jump

over the fence and descend upon the family.

Often, the whole house is ransacked to make sure that the

"Sha'biya family" does not

have weapons. The members of the family who are selected for

deportation are then taken

away to a detention center.

In 54% of the cases they are not told that they are being

deported

In 92.5% of the cases they are not told how they will travel

In 96.1% of the cases they are not informed how many days the trip

will take

Instead, most of them (53.0%) are told that they are needed at

the police station or local

administration (Kebele) for just a few minutes and that they will go

right back to their

homes. The majority of these men and women never see their families

again. They go on

the long trip in a helpless state, often still wearing their night

clothes. If there is a bus ready

to take them to Eritrea, they may begin their trip in that state.

This pattern of deceptive behavior becomes less confusing and

humiliating if the

prospective deportee is kept in a detention center for a few days

and the family is allowed to

visit him or her. During that time the family has a chance to accept

the fact that the

uprooting process had begun and to make some necessary preparations.

As we shall see

later, however, the family often has no visitation rights.

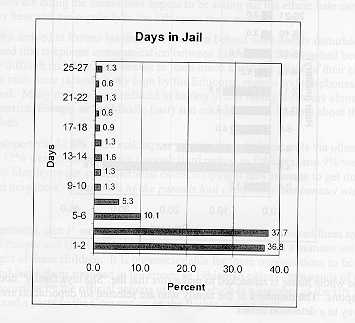

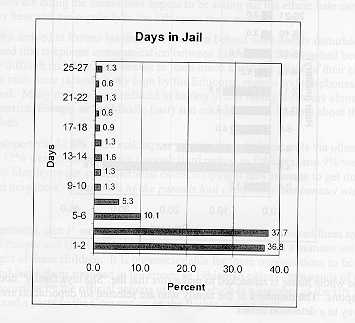

Detention or Internment

The detention centers are large collection camps, most of

them located some

distance away from urban centers and curious eyes. The majority of

the detainees (52%)

are kept in custody from one to six days, but it can be as long as

27 days. 20

The purpose of detention is partly collection, partly

interrogation, and partly

humiliation. The interrogations were fairly methodical in the early

stages of the conflict but

they have now become much more perfunctory or are entirely left out.

The statement of an

informer is now sufficient to get an ethnic Eritrean deported out of

Ethiopia.

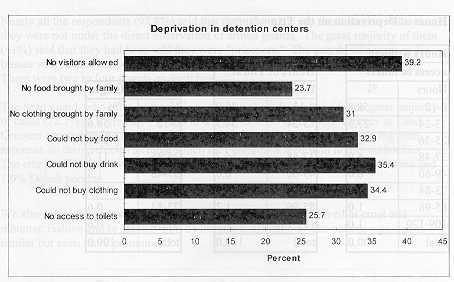

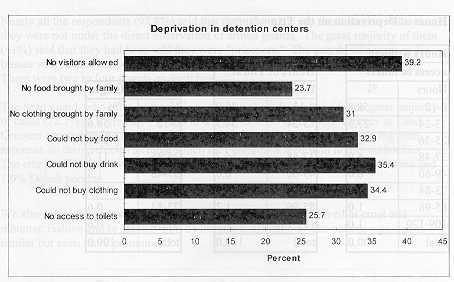

Violations of the rights of prisoners in detention centers

Once they have been put in custody, citizens of Eritrea and

ethnic Eritrean citizens

of Ethiopia are treated in ways that violate their rights of

visitation, food, drink, clothing

and access to toilet facilities. 21

Our data show that in 39% of the cases, relatives of the

detainees were not allowed to

visit them. Some 23.6% of the deportees said that relatives were not

allowed to bring them

food. Even when the detainees wanted to use their own money to buy

food or drink, they

were prohibited from doing so in 33 and 36 percent of the cases

respectively. It is worth

remembering that the detainees were rarely supplied with food or

drink by their jailers.

Often there were no toilet facilities and people had to use the

same rooms in which they

lived and slept for such purposes. In 26% of the cases, people were

denied access to toilets

for extended periods of time.

Duration of deprivations

The deportees suffered various forms of cruelty on the trip

to Eritrea. Most were

deprived of food for 12 to 36 hours but some as many as 4 days. On

average, they were

deprived of water for 12 to 48 hours, but some for as many as 5

days. They were

commonly deprived of access to toilet facilities for 12 to 24 hours

but some times for as

long as 5 days.

One of the worst cases on record is a bus in which the deportees

were told to use the

bus as their toilet. In desperation and with a sympathetic guard

pretending not to notice, the

men were able to use an empty jerrican as a urinal. The situation

was bad enough to cause

the death of one of the deportees.

Hours of Deprivation on the Trip

Hours without access to toilets

|

Hours |

% |

|

0-12 |

58.8 |

|

13-24 |

27.5 |

|