Two of the world’s and Africa’s oldest kingdoms have long unwittingly vied for dominance and influence on the motherland. And though cultural and economic ties seem to have brought Egypt and Ethiopia together on some level, the two power players are at odds regarding the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). But could it be a show of muscles at a time international businesses are rushing to invest in Africa? Or, is it a conflict over limited water and energy resources?

Egypt’s diminishing influence in the Middle East and North Africa might provide a context for the country’s strife for power and sway over the African continent. After Abdel Fattah al-Sissi rose to power at a hefty expense, Egypt’s economy shrunk and crumbled in a way it hasn’t as severely under the former autocratic rule of Mubarak. Less economic opportunities coupled with the regime’s crack-down on freedoms isolated Egypt and diminished its role in the region.

Having been distant from other African countries, especially culturally, al-Sissi’s Egypt rekindled its relations with the continent through a number of initiatives and investments. Its announced and unannounced intentions are palpable. Egypt’s hegemonic relations with countries like Sudan and Eritrea are a strong ground to Sissi’s desire to have a more sturdy role than that in the Middle East.

Less economic opportunities coupled with the regime’s crack-down on freedoms isolated Egypt and diminished its role in the region

The North African country was also praised by South Sudanese President, Silva Kirr for supporting stability in the nascent country. Kiir additionally hailed the developmental initiatives and scholarships provided by Egypt to the South Sudanese. As for other Nile Basin countries, Egypt’s intelligence has assumed a number of posts there. Egypt has also repeatedly supported both Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo in their presidents’ endeavours to seize control unconstitutionally through rejecting the UN’s call for sanctions.

But the most powerful relationship Egypt is refining is with Uganda, an unannounced adversary of Ethiopia.

Ethiopia’s powerplay isn’t dimming, especially after Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s win of the Nobel Peace Prize this year. The 42-year-old and youngest African leader is being given the prestigious award in recognition for his peaceful efforts with the neighbouring country, Eritrea and reaching a peace deal to end an almost 20-year border conflict.

The recognition won him wide regional and international praise. It also shed light on his internal reforms, from distancing his administration from theabuses of former ones to giving competent women high posts within his government.

Abiy’s sweeping political and economic reforms garnered a set of interests and investments from the United States and China. And, akin to Egypt’s attempts to cosy up with other Arab countries, Abiy announced in November, 2018 the implementation of visa-on-arrival regimes for African travellers.

That along with Abiy’s attempts to alleviate ethnic tensions has moved the country’s ranking up enough to gain major global and regional clout. But are Egypt’s vetoes against filling the GERD as well as its operation trampling said clout?

Egypt has historical precedents treating the River Nile as its own, from treaties with then-colonial power, Great Britain and Sudan, to direct military threats against Ethiopia. In fact, Egypt aggressively pursued a higher share in its 1959 treaty with Sudan from 48 billion cubic metres to 55.5 billion cubic metres.

Abiy’s attempts to alleviate ethnic tensions has moved the country’s ranking up enough to gain major global and regional clout

Ethiopia continues to reject Egypt’s threatening tone. But is Egypt merely pursuing a hostile attitude to a regional issue or is it a frantic effort to pressure its water supply?

The Nile has long been revered since ancient Egypt. Ancient Egyptians actually believed the Milky Way was but a reflection of the Nile. The river is also an emblem of Egypt’s fertility and culture.

90% of Egypt’s water needs come from the River Nile, 60% of which comes from Ethiopia’s Blue Nile, while the rest flows from Sudan’s White Nile. And, with a population of almost 100-million-people, Egypt has one of the lowest per capita water share in the world at around 660 cubic metres.

And, while Egypt’s population is projected to reach 140 million people by 2050, water shortage is expected to happen as soon as 2025 without the GERD being a factor. According to officials at Egypt’s ministry of irrigation, Egypt would lose 20%-30% of its Nile water share which could lead to a 30% decrease in electricity coming from the Aswan Dam.

90% of Egypt’s water needs come from the River Nile, 60% of which comes from Ethiopia’s Blue Nile

Also, a Cairo University professor suggested in a study that Egypt could lose up to 51% of its farmland if Ethiopia fills the dam in three years.

While Ethiopia insists the dam won’t highly impact Egypt’s share of water, one main concern stands out which is the high salinity of Egypt’s Nile Delta soil, a largely agricultural area.

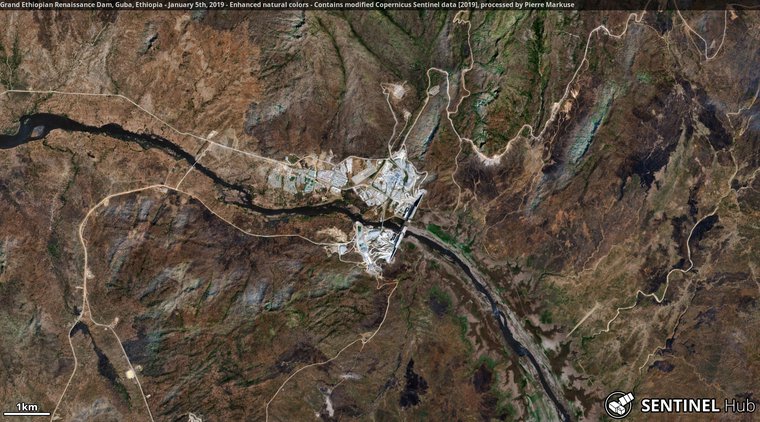

With Ethiopia’s ethnic divisions threatening its stability and the country ranking 174th out of 187 countries in a human development report released by the UNDP in 2011, Ethiopia hopes the $4.7 billion hydroelectric project will be crucial for Ethiopia’s frail economy and mostly poor population. At full capacity, the dam should be able to produce over 6,000 megawatts of electricity. This alone should bring the country to the 21st century, especially that Ethiopia has long suffered from severe power shortages as only 44% of its 105-million-people population have access to electricity. Also, 42% of the population has access to clean water, only 11% of which can get sanitation services.

Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan met for discussions for two days last week, but still managed to end with a bigger rift, suggestion of new conditions on one side and a call on South Africa for mediation on another.

Ethiopia’s Minister for Water and Energy Sileshi Bekele blamed the Egyptian side for the lack of willingness to reach an agreement saying his government does not accept Egypt’s suggestion of filling the dam over 12-21 years, a claim Egypt refuted in Egyptian media.

The three countries are meeting today in Washington to try and reach a proper agreement that would suit the three parties though a war of words is more likely before international arbitration is finally triggered.

It is not a race between the countries most in need of water resources but evidence begs the question of whether the dam is both vital and threatening to Ethiopia and Egypt, respectively. It is also rather apparent that both countries are competing for a higher diplomatic status.