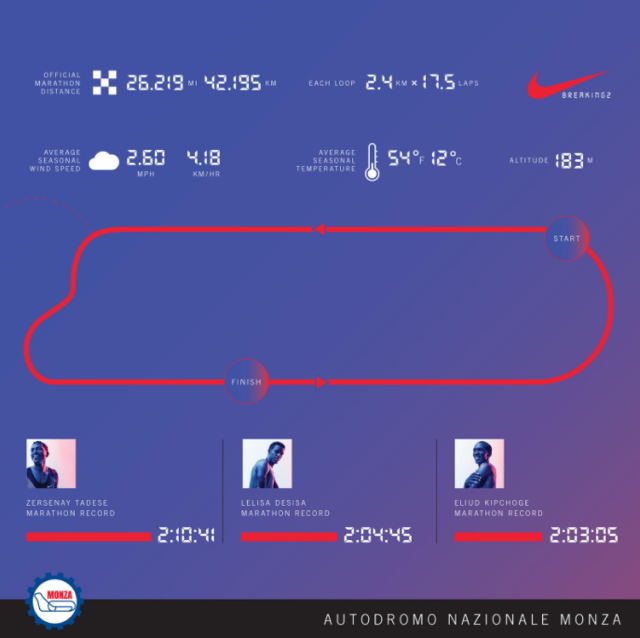

Early Saturday morning in Monza, Italy, a trio of legendary runners met up on the city’s Formula 1 racetrack to do the impossible: Break the 2-hour barrier for a full marathon run.

A marathon is a little over 26.2 miles. The fastest marathon time ever recorded, per the IAAF, was set in 2014 by Kenyan runner Dennis Kipruto Kimetto in Berlin, clocking in at 2:02:57. Driving the feat was Nike and its agency Wieden + Kennedy, with help from a bevy of partners like content studio Dirty Robber.

Spoiler: None of the runners ended up breaking the barrier, though Eliud Kipchoge came incredibly close, finishing at 2:00:25—a colossal 2:32 under Kimetto’s IAAF record. Sadly, this run won’t be counted as a world record breaker.

But in addition to challenging the mental barrier we’ve built around 2 hours, Nike’s “Breaking2” deserves recognition for what it meant simply to take this on.

Breaking2 has been in the works for what W+K simply tells Adweek was “a looong time”—and to come even close to breaching the barrier, Nike needed to ensure all conditions were perfect.

In terms of planning, marketing and ambition, it’s easily comparable to 2012’s Red Bull Stratos—which The Drum rightly calls “the high watermark of content marketing productions”—even if the feat is literally much closer to Earth.

To fully appreciate what “Breaking2” accomplished, it helps to understand the technicalities. Nike called this a “moonshot,” partially inspired by the moment Sir Roger Bannister ran the first 4-minute mile in 1954, redefining what athletes were capable of.

“The real purpose of running isn’t to win a race, it’s to test the limits of the human heart,” says Nike co-founder and track coach Bill Bowerman.

Running a marathon in under two hours means shaving seven whole seconds off the average number of minutes Kimetto spent on each of his marathon miles. He ran each mile at an average 4:41. That means Nike’s athletes had to clock an ideal figure of 4:34 per mile—far from under 4 minutes, granted, but try holding that pace down for a whole marathon.

If you’re a regular runner, you know it’s easy to beat your time for one mile, maybe two or three, but consecutively over 26 miles while maintaining an average of nearly 4:30 per mile is trying, even for the best runners. As Oregon Live put it, “Succeeding would be a little like Babe Ruth coming to the plate, stepping out of the batter’s box, pointing at the outfield fence, then hitting one out.”

Many argue that running a sub-2:00 marathon simply isn’t possible—partly because the runners themselves may not be fast enough, but also because of, well, math.

Per LetsRun.com, a sub-2:00 marathon demands a minimum 2.41 percent improvement on the previous world best—which would be the biggest improvement by far over the past 50 years. Even as marathons grow more frequent, the improvement rate has never crossed 1 percent.

In Nike’s defense, the brand’s partners seemed aware of this. “When you plot out world records, it should take a couple decades to get to where we want to be,” says Dr. Philip Skiba, a performance engineer for Advocate Medical Group, in the video below.

“But no one’s ever gone flat-out from the gun before. That’s what I think is so amazing about this project: We’re gonna tell these guys you’re gonna go for it from the gun, and whatever happens happens. That, I feel, is a recipe for greatness.”

The first thing Nike needed to do was ensure it had the runners best equipped to do the job. This isn’t just a matter of how fast they run; they also tested for runners’ amount of oxygen intake, how much energy they conserve while running, and ability to sustain speed for the longest possible time.

And given that the feat’s never been done before, they also needed athletes committed to beating not only their best times, but also the best marathon time ever.

Ultimately Nike settled on Kenyan runner Eliud Kipchoge, Ethiopia’s Lelisa Desisa and Eritrea’s Zersenay Tadese. Each runner was actually paid to forego this year’s London and Berlin Marathons in order to invest in this effort.

To promote “Breaking2,” W+K organized a full holistic campaign around the effort, the runners and the innovation required to make this happen. Below is the trailer that introduces you to the three challengers.

This trailer was reinforced by separate videos for each runner.

Kipchoge is 32 years old. In 2012, he set a half-marathon best with a time of 59 minutes and 25 seconds. Ever the overachiever, he improved his personal best marathon time by 5 seconds when he won the Berlin Marathon, clocking in at 2:04:00. At the London Marathon in 2016, he set a new course record when he clocked in at 2:03:05.

Well before the run began, he was already labeled a favorite to come even close to beating Kimetto’s record.

Next up, Tadese, a 34-year-old who took the 20-kilometer title in the 2006 IAAF World Road Running Championships, making him Eritrea’s first World Championship winner.

In 2009, he became the second man to win three World Championship medals over three different surfaces in the same year. Dubbed the “Rocky Balboa of this group” in the video below, he currently holds the men’s half marathon record, with a time of 58:23.

Last but not least, 26-year-old Desisa, who began his running career as a road racer. His marathon debut at the 2013 Dubai Marathon clocked at 2:04:45. After winning the 2013 Boston Marathon, he returned his medal to the city of Boston to honor its bombing victims. In 2015, he won Boston again, with a time of 2:09:17.

On top of putting together its dream team, Nike ensured that all three were equipped with a specially designed lightweight racing flat, a shoe design that’s been in the works for three or four years. The shoes were also modified after initial feedback from the athletes, who had reported it was painful on concrete.

The resulting lightweight, resilient and soft-padded Nike Zoom Vaporfly Elite includes carbon-fiber plating for added propulsion. Its heel is also more elongated than normal shoes, reducing drag. You can also learn more about the rest of the athletes’ individual kit.

We’re not done with all the prep yet. Nike wanted to control for three more variables: Weather, the course, and optimal pacing. See why we’d so readily compare this to Stratos? You can’t just throw three pedigreed runners onto a track and expect them to do for a brand what no one’s ever been able to do in the entire history of their sport.

In fact, Nike’s been working on building its athletic cred for a long time. Its senior director of performance, Ryan Flaherty, earned the nickname “The Savant of Speed” and can be heard talking about his efforts in Tim Ferriss’ latest podcast.

Flaherty developed an algorithm called “Force Number,” based on the hex (or trap) bar deadlift and body weight to predict speed, like in the 40-yard dash. Before taking on Nike’s performance needs, he helped train athletes like Serena Williams, The Arizona Cardinals and Marcus Mariota. He also worked directly with the runners on Breaking2—and athletes and coaches seek him out for guidance on injury prevention or training.

So Nike isn’t working with lightweights, and Breaking2 solidifies its ability to level athletes up safely while understanding the complexities they face, including the impacts of terrain, weather, wear and hydration on performance. It also demonstrates that cost is no object when it comes to ensuring the best possible variables.

That athletes would trust it to level them up, even foregoing official record-holder titles (a big ask in what are generally short, unforgiving physical careers) is a massive point in Nike’s favor—not just as a serious athletic brand but also as a marketing powerhouse. To put it short, they knew Breaking2 would be worth the sacrifice.

Back to prep. Let’s start with weather: This is one of the reasons Monza was chosen. Its average temperature right now is perfect for marathoning (53 degrees Fahrenheit), with overcast skies, minimal wind and reasonable elevation (600 feet above sea level).

Next is the course: Monza’s Formula 1 Grand Prix course, located just outside Milan, is flat and oval-shaped with gradual turns—meaning less energy spent making a sharp directional change. Its track also guarantees good consistency underfoot, a lack of banks for a clear, even pitch, and an ideal length of 2.4 kilometers (1.49 miles), making it ideal for managing pacing, hydration, nutrition and support team transitions.

It merits saying here that athletes also didn’t have to stop, ever, for hydration. They could drink whenever they want, and bottles were shuttled via moped. This is one of the reasons Kipchoge’s 2:32 break from Kimetto’s legendary marathon time isn’t actually considered record-breaking.

17 fluid bottles contained between 60 to 100 ml of fluid per athlete, with 12-14 of their bottles containing a standardized drink; 3-5 contained a special mix.

“The total fluid volume in each of the special bottles is different from the others and they will have either a higher concentration of sugar or a different type of sugar or a sugar and caffeine combination,” explains Dr. Brett Kirby, researcher and lead physiologist of the Nike Sport Research Lab.

Last comes ideal pacing. To ensure Kipchoge, Desisa and Tadese never lost sight of their optimal pace, a Model S electric car drove about six meters ahead of them, reflecting the race pace, amount of time passed and the projected marathon finish time.

“This is typical of most road races, but the Breaking2 lead car will update this info every 200 meters whereas other races typically update these stats every kilometer or 5K,” says Kirby.

A team of 30 “pacers” were also hand-selected to accompany the athletes to help them maintain a steady pace and create wind divergence. These included Bernard Lagat, Chris Derrick, Sam Chelanga, Andrew Bumbalough and Stephen Sambu. They were chosen based on their running abilities and temperament.

“We needed calm, steady pace runners who can run the same speed repeatedly,” adds physiologist Dr. Brad Wilkins, who also serves as director of Nike Explore Team Generation Research in the Nike Sport Research Lab.

18 pacers were reserved for the lead runner, while six were reserved for the lead running group; another six making up the second running group. They ran in a triangle formation, with just six pacers on the course at a time for the lead group.

“We landed on the pacer formation based on wind tunnel experiments performed in fall 2016 by Nike Sports Research Lab at the University of New Hampshire wind tunnel and our collaboration with Winning Algorithms,” says Kirby. “Coupled with computational fluid dynamics (for example, aerodynamics modeling), we chose the best formation of pacers to block the wind.”

Each pacer covered two laps before exchanging with relief pacers. Only three pacers could enter or exit the exchange zone at a time, but a pacer exchange occurred for every lap. “It’s a choreographed change-in that has to happen without us losing a second of speed,” says Kirby.

So what happens next? The run, of course.

The run was broadcast live exclusively on Twitter, YouTube and Facebook. “We’re as shocked as you are that no network jumped to broadcast a two-hour run,” a representative from W+K jokingly told Adweek. Rewatch it below.

The broadcasts garnered over 486,000 views on YouTube and a whopping 5.2 million views on Facebook. On Twitter, the #breaking2 hashtag is still going strong—especially as fodder for morning inspiration.

The actual race took place at 5:45 a.m. on Saturday in Monza. Kipchoge crossed first at 2:00:25, beating the world record by 2:32—also 2:40 under his own personal best of 2:03:05. Tadese followed at 2:06:51, beating his personal best by a whopping 3:50, and Desisa—the youngest of the pack—crossed the finish at 2:14:10.

At the finish, Kipchoge said, “This is history.” On Nike’s #Breaking2 live Twitter feed, he added, “I’m happy to have run two hours for the marathon … My mind was fully on the two hours but the last kilometre was behind the schedule. This journey has been good—it has been seven months of dedication.”

For Nike, this story is far from over. A Breaking2 documentary is slated for release this summer in collaboration with National Geographic, and vp Matt Nurse of the Nike Sport Research Lab suggests it may try other “moonshots” to help athletes achieve the extraordinary.

“We are already discussing other moonshots, perhaps related to female athletes. It’s not one and done, it just may take a different form next time,” he says.

Of course, the brand’s also set a benchmark for competitors—Adidas is planning its own sub-2:00 run, complete with its own shoe launch. With two years of development under its belt, Adidas also claims its barrier break will happen on an established course. Notably, official world record-holder Kimetto is an Adidas athlete.

As perhaps a testament to its own confidence, Adidas proved a very good sport on Saturday morning:

“Today, I have learned that the impossible is possible. The next generation should know that nothing is impossible in this world. Real focus, determination and real hope, can take you somewhere,” Kipchoge added after the race.

“Let all generations from all the world have hope, because the hope of when we first came here, the hope of running under two hours, was two minutes and 57 seconds. Now we are only 25 seconds away.”

Meanwhile, riding on the tide of all this delightful earned media, spanning from one side of the globe to the next, the Nike Zoom Vaporfly Elite will go on sale sometime this year.