Date: Tuesday, 18 September 2018

By Lisa Watanabe for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

18 Sep 2018

Although irregular migration to Europe has declined, avoiding a recurrence of events in 2015 is seen as paramount. The EU is increasingly relying on cooperation with third countries to reduce migration pressure. Such cooperation, however, often fails to sufficiently consider the political and economic contexts of partners, which could ultimately compromise the EU’s own migration aims and values.

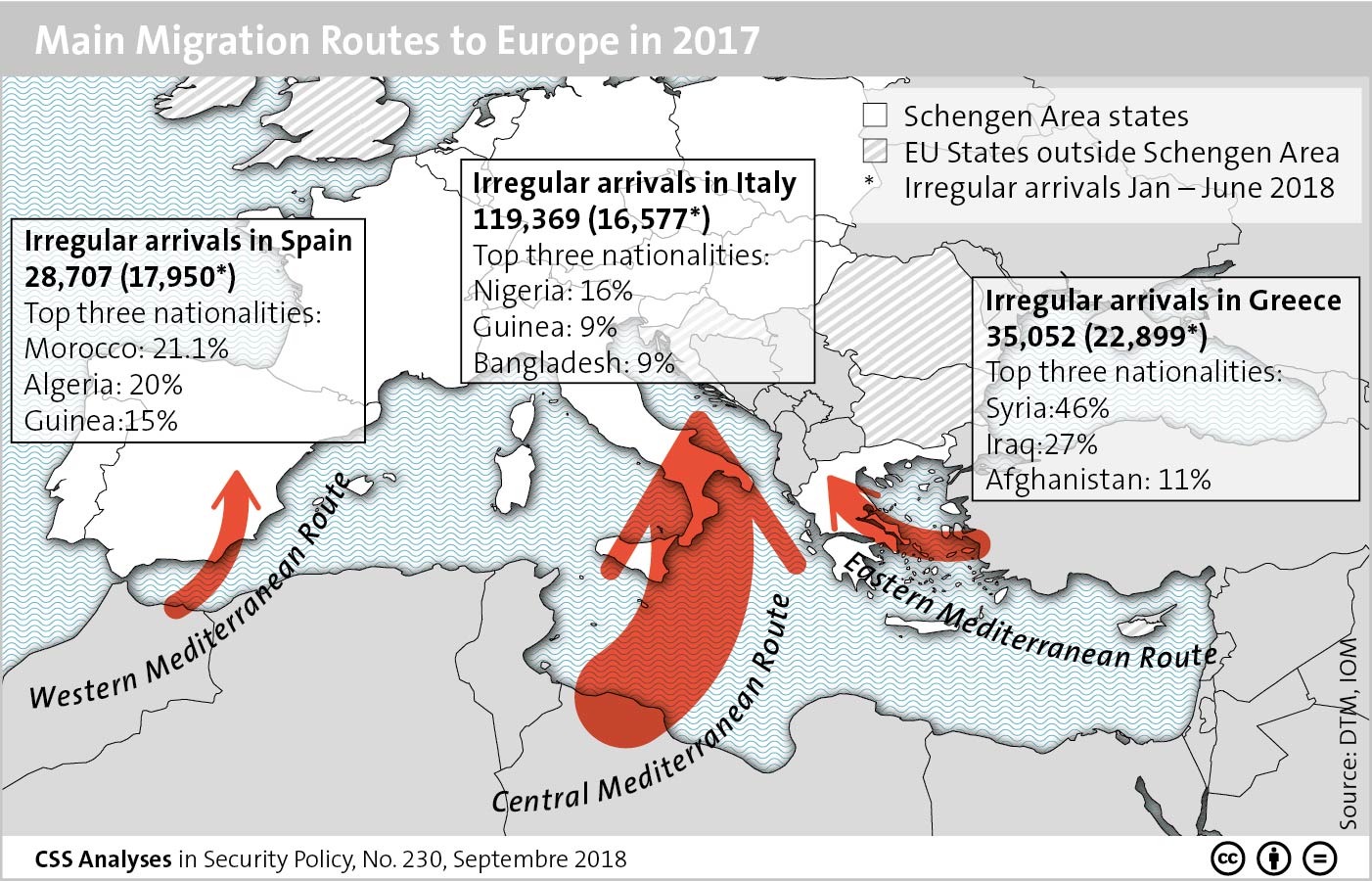

Irregular arrivals in Europe have been declining over the past three years. Whereas over one million people arrived irregularly in 2015, the figure had dropped to 382,000 in 2016, and fell further in 2017 to roughly 186,000. With approximately 58,000 irregular arrivals during the first half of 2018, the downward trend could be set to continue this year. The overall reduction in numbers is mainly the result of fewer migrants and refugees taking the Eastern Mediterranean Route (principally from Turkey to Greece), due in part to increased cooperation on migration between the EU and Turkey, as well as the near-closure of the Western Balkan Route (mostly from Greece to Hungary or Croatia via Macedonia and Serbia).

In addition to the reduction in the total number of irregular arrivals, the relative importance of the Mediterranean migration routes has been shifting. From late 2015 to the end of 2017, as the Eastern Mediterranean Route gradually became less significant, the Central Mediterranean Route (mostly from Libya to Italy), which was the main route in 2014 (see CSS Analysis No. 162), once again became the principal route for those trying to reach Europe irregularly. 2017 also saw a revival of the Western Mediterranean Route (mostly from Morocco to Spain), which was once considered largely closed as a consequence of longstanding cooperation on migration management between Morocco and Spain. The relative weight of these routes could change yet again in 2018.

The nationalities of those attempting to enter Europe irregularly have also been changing. When irregular migration to Europe peaked in 2015, Syrians, Iraqis, and Afghans tended to be the most heavily represented nationalities, especially along the Eastern Mediterranean Route. However, as the Central and Western Mediterranean routes have taken on greater importance, a larger proportion of those arriving irregularly in Europe tend to come from countries in North, West, and East Africa. The African continent has thus become an increasing source of irregular migration to Europe for a variety of reasons, including lack of economic perspective and instability.

Internal Migration Management

Although irregular arrivals have declined since 2015, crises in Europe’s neighborhood could see them peak again. Were this to happen, the EU could still struggle to cope. At the heart of the problem are deficiencies in its Common European Asylum System (CEAS), notably the Dublin Regulations, which were initially created outside the EU framework in 1990 and later incorporated into EU law in 1999. They now apply to all 28 EU countries plus Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland. According to these rules, the first country in which an asylum seeker arrives in the Dublin Area is usually responsible for processing his or her asylum application. Hence, a disproportionate burden is placed on the main countries of arrival along the common external border, such as Greece and Italy. Placing these countries under too much pressure increases the chance of secondary migration movements on to other Dublin states, due to a failure to register every new arrival and variations in the treatment of asylum seekers in EU/Dublin states that can encourage asylum seekers to try to reach countries where they believe their asylum chances may be high.

Secondary movements not only undermine the Dublin system, though. They can also compromise the EU’s principle of free movement of people by making one of its elements, namely border-control-free travel, less feasible. The latter is based on the 1985 and 1990 Schengen Agreements. Like the Dublin Regulations, they were initiated outside the EU and subsequently integrated into EU law in 1999. Today, the Schengen Area consists of 22 EU countries as well as Lichtenstein, Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland. In 2015, fears of irregular secondary movements prompted Hungary and Slovenia, two EU Schengen states, to construct fences. Additionally, a number of EU/Schengen states (Germany, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Austria) temporarily re-imposed border controls on the grounds of either anticipated secondary migration movements or resultant threats to public policy.

In order to restore the normal functioning of the Schengen Area, the EU has taken a number of measures to improve security at the external Schengen border. So-called hot spots (special processing centers) were established in Greece and Italy to ensure that all new arrivals are registered and their fingerprints entered into the Eurodac database, which Dublin states can consult to determine where asylum seekers first arrived. A European Border and Coast Guard Agency (EBCG) was also created from Frontex (the EU’s border management agency) to increase oversight of Schengen countries border management, boost operational support available to them, facilitate action in urgent situations, and improve coordination between EU member states and third countries on the return of those who do not qualify for asylum. In addition, the Schengen Border Code was modified to allow for checks on all individuals crossing the common external border, including nationals of EU/Schengen countries.

Switzerland and European Migration Cooperation

Switzerland contributes to developments in response to events in 2015 through its Schengen/Dublin Association Agreements, as well as through its voluntary participation in some EU agencies and initiatives. In solidarity with other Dublin states, Switzerland agreed to take in 1’500 people from Italy and Greece under the EU’s Relocation Programme, and Swiss asylum specialists have been deployed to the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) to assist with operations in hot spots established in Greece and Italy. Switzerland also intends to contribute personnel to the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (EBCG) and to help it improve the rate of returns of third-country nationals irregularly staying in the Schengen Area. Switzerland has also adopted the amendment to the Schengen Border Code that introduced systematic checks of all people crossing the Schengen borders, including those from Schengen countries, and will be bound by any further modifications to the Schengen Border Code.

While most of the proposed changes to the EU’s common asylum system do not relate to Switzerland as a non-EU country, some do. Switzerland’s current contribution to EASO means that it would likely choose to participate in the proposed European asylum agency. Any changes to the Dublin Regulations would also be of relevance to Switzerland. If a mandatory solidarity mechanism is agreed, which seems unlikely, Switzerland would be obliged to participate in it. However, if a voluntary solidarity mechanism transpires, Switzerland would not be obliged to participate in it, but would probably choose to out of solidarity.

To advance its migration objectives, Switzerland has bilaterally concluded migration partnerships with non-EU third states, some of which are relevant to the Central Mediterranean Route (e.g., Tunisia and Nigeria), and also cooperates with international organizations, including the UNHCR and IOM. While some of these actions are informally coordinated with the EU on a local level, they remain distinct from the EU’s external dimension of migration management.

To alleviate pressure on Greece and Italy, the EU established a relocation program to redistribute those likely to qualify for asylum to other countries within the Union, as well as to non-EU Dublin countries that choose to participate. However, progress has been slow, and some EU states have refused to accept mandatory quotas of people in need. Diverging positions regarding the question of burden-sharing have similarly deadlocked discussions on modifications to the Dublin Regulations. In a gesture towards greater solidarity that falls short of the European Commission’s proposed automatic relocation mechanism, EU member states have agreed that secure centers for processing those rescued at sea should be established in EU countries, albeit on a voluntary basis. They also intend to explore the possibility of regional disembarkation centers in third countries. Negotiations are also progressing on less controversial measures, such as reinforcing the Eurodac database, further harmonizing the treatment of asylum seekers and reception conditions and transforming the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) into an asylum agency to facilitate the implementation of reforms.

Cooperation with Turkey

In contrast to the slow pace of reforms in the EU’s CEAS, particularly those that would modify the Dublin Regulations and affect how many asylum seekers EU/ Dublin countries would receive, cooperation with third countries to reduce irregular arrivals has advanced apace. To reduce departures from Turkey to Europe, the EU concluded a Joint Action Plan with Turkey in October 2015, under which Turkey agreed to align its visa requirements with those of the EU, especially with regards to countries that constitute a significant source of irregular migration to Europe, notably Syria; increase the interception of those trying to enter Greece irregularly from Turkey; improve cooperation on the readmission of migrants who passed through Turkey but do not qualify for asylum; and combat smuggling networks. In return, the EU agreed to improve exchange of information on smuggling networks with Turkey, as well as to provide financial support for both Syrian refugees hosted in Turkey and capacity-building for the Turkish Coast Guard.

In order to further reduce irregular arrivals from Turkey to Greece, the EU and Turkey issued a joint statement in March 2016. In it, Turkey pledged from that time on to readmit all those who crossed from Turkey to Greece and either do not apply or qualify for asylum, as well as all of those rescued in Turkish territorial waters. In recognition of this, the EU agreed to reinvigorate Turkey’s EU accession process, accelerate the lifting of visa requirements for Turkish citizens, and resettle one Syrian from Turkey to the EU for every Syrian returned to Turkey.

Measures taken by Turkey do appear to have contributed to a reduction in the number of irregular arrivals via the Eastern Mediterranean Route. However, cooperative arrangements with Turkey are not legally-binding international agreements. As such, they leave the EU vulnerable to threats by the Turkish government to cease cooperation, which has continued despite tensions in EU-Turkey relations following the attempted coup in 2016. Doubts also exist as to whether the EU-Turkey statement in particular upholds international protection standards. Turkey’s status as a safe country to which Syrians can be returned is disputed, since Turkey only grants full asylum to non-European refugees and is believed to have violated the non-refoulement principle by turning Syrian asylum-seekers away at the Turkish border.

Reducing Transit through Libya

Despite the shortcomings of the so-called EU-Turkey deal, its impact on irregular arrivals has encouraged the EU to seek similar arrangements with countries relevant to the Central Mediterranean Route. As the main departure point for Europe on this route, Libya would have been a prime candidate for such a deal. However, the lack of a reliable governmental partner has circumscribed the scope of EU-Libyan cooperation. The EU remains limited to training the Libyan Navy and Coast Guard to combat people trafficking and smuggling in Libyan waters through its operation EUNAVFOR Med Sophia, and the gradual re-establishment of its border management mission, EUBAM Libya.

Given the limits to what the EU itself can do in Libya, the Union endorses and partially finances Italy’s efforts to work with a number of Libyan actors to curb irregular migration. The basis for this cooperation is a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed by Italy and the UN-backed Libyan Government of National Accord in February 2017. In the MoU, Italy agreed to work with Libyan institutions responsible for tackling irregular migration and securing Libyan borders, as well as to provide development assistance to help create alternative revenues for communities reliant on people smuggling and trafficking. From this starting point, cooperation has expanded to include engagement with a number of additional intermediaries, including tribes and mayors.

The resultant increased control of Libya’s maritime border in particular has led to a decline in departures from Libya to Italy, seemingly vindicating initiatives undertaken or endorsed by the EU. However, the measures taken by the EU and Italy have also heightened the vulnerability of migrants and refugees in Libya by increasing the length of time spent in “safe houses” provided by smugglers, as well as exposure to the risk of kidnapping, extortion, and abuse in both official and unofficial detention centers. As their plight has become apparent, the UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) have stepped up operations to evacuate migrants to their countries of origin and resettle refugees in safe third countries, which the EU obviously supports.

Cognizant of the need to engage a wider set of origin and transit countries to reduce transit to Libya, the EU has since mid- 2016 entered into country-specific, non-legally binding political agreements or so-called compacts with Ethiopia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, and Senegal. The compacts are largely financed by a new funding instrument, the Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, created in 2016. To maximize leverage vis-à-vis third countries, they draw on a range of policy areas (development, trade, security, education, and mobility), as well as existing bilateral migration cooperation between third countries and individual EU member states, and employ positive and negative incentives. The EU’s stated short-term aim is to combat people smuggling and trafficking, increase the return of those staying irregularly in the EU to countries of origin and transit, encourage migrants and refugees to stay close to home, and increase the possibilities for resettlement in the EU for those qualifying for protection. Over the long term, the compacts are also supposed to address the drivers of irregular migration.

So far, the compacts have led to some progress in the area of combating people smuggling and trafficking, and also in improving border security. However, they are generally failing to deliver on the EU’s goal of increasing readmission. Sub-Saharan African countries tend to rely heavily on remittances from diaspora communities in Europe and are thus reluctant to cooperate on this issue. The compacts have also been criticized for subordinating development aid, trade relations, and other policy areas to the EU’s migration agenda, which could be counter-productive over the long run. Moreover, the heavy focus on keeping migrants and refugees close to home is not complemented by measures to ensure that the rights of migrants and refugees will be respected. In addition, the promise of greater pathways to resettlement to the EU may not materialize, given how contentious accepting refugees has become in Europe.

Partnering North Africa

A similar mismatch of agendas has also marred cooperation between the EU and North African countries with which the EU would like to cooperate more closely on migration in order to prevent them from becoming key departure points to Europe in Libya’s place. Migration cooperation with them has traditionally occurred within the framework of the European Neighbourhood Policy through Mobility Partnerships, where partner countries agree to strengthen their border controls and readmit nationals who are irregularly staying in the EU, as well as to take back third-country nationals who transited through their territories. The promised benefits of such cooperation primarily include visa facilitation for select categories of people, such as students and businesspeople, and enhanced legal pathways for labor migration to the EU.

Nevertheless, so far, Morocco and Tunisia are the only North African countries to have concluded Mobility Partnerships, in 2013 and 2014 respectively, and cooperation on readmission and return has been slow. As with sub-Saharan African countries, remittances are very important to North African countries, and returns of third-country nationals are contentious, as it could be difficult to repatriate them to their home countries. The anti-immigration climate in EU member states has also made it hard for the EU to deliver on visa facilitation and increased mobility, reducing the EU’s leverage and generating cynicism among its partners.

The EU is now hoping to use the added flexibility provided by the Emergency Trust Fund for Africa to provide a new impulse to migration cooperation with North African countries, especially Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia. This does seem to have paid some dividends. In 2017, Egypt began a dialog on migration with the EU, and new migration-related projects have been started with Morocco and Tunisia. However, the additional assistance that the EU is offering may not be enough to encourage progress on readmissions and return. It is also unlikely to extend to hosting regional disembarkation centers. Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia have already refused to host such centers.

A Sustainable Approach

To be sure, cooperation with third countries does need to form part of the EU’s approach to migration. However, cooperative arrangements that are too heavily weighted in favor of the EU’s short-term aim of discouraging migrants and refugees from attempting to reach Europe and that neglect third countries’ migration interests are likely to lead to disappointing results, even with the application of penalties for poor cooperation. Worse still, they are likely to consciously compromise the rights of refugees and migrants. The EU needs to develop a more sustainable approach to managing migration that adopts a more long-term and realistic view of partners’ local contexts. This should not, however, be seen as a substitute for a unified and effective way of coping with irregular migration within the EU itself, if the Union and wider Europe are to avoid a repeat of events in 2015.

Dr. Lisa Watanabe is Senior Researcher at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich. She is the author of i.a. Borderline Practices – Irregular Migration and EU External Relations.