On Sunday, diplomats will gather in Khartoum to witness the signing of Sudan’s new constitutional declaration – a power-sharing agreement between protesters and the armed forces. Yet the international community cannot turn away in satisfaction: the country is not at peace, and the new administration will come to be judged on what happens miles from the capital, in the marginalised conflict zones of Darfur, Blue Nile and South Kordofan.

Since the protests began in December, little attention has been given to the long-running conflicts in those regions, where non-Arab citizens have endured years of persecution by Khartoum-backed militia. Will the brutal but influential Rapid Support Forces (RSF) continue to ethnically cleanse African Sudanese, their atrocities largely unnoticed in the capital or by the international community? Their leader, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti, is believed to be the most powerful military representative on the new transitional authority.

Niemat Ahmadi of the Darfur Women’s Action Group warns that unless decades of marginalisation are reversed and Hemedti’s RSF is reined in, there will be neither peace nor prosperity in the new Sudan. “The elites in Khartoum are still repeating the exclusive approach that has divided the people of Sudan for years and led to genocide in Darfur,” she says, arguing there must be justice and accountability.

Years of misery in Darfur

Since 2003, the self-identifying ethnic Arab militia known as the Janjaweed, now rebranded as the RSF, has attacked non-Arab villages across the remote Darfur region. The UN estimated Darfuri casualties at 300,000 in 2008. Half the population of six million people fled either across the border into Chad, where more than 300,000 remain sixteen years later, or to internally displaced people’s camps, where 1.5 million continue to live in dismal circumstances.

Human Rights Watch and other impartial monitors have catalogued the systematic rape of girls and women by the RSF, the murder of boys and men, the looting of livestock and the destruction of non-Arab communities. Although the mainstream media has moved on from Darfur, non-Arab citizens there continue to be terrorised by the RSF and its proxies. In July this year, the UN assistant secretary-general, Andrew Gilmour, confirmed the persecution of civilians had again reached worrying levels. “We believe that many cases in Darfur remain invisible and under-reported due to lack of access to some parts of the region,” he said.

Gilmour was referring to the absence of passable roads in an area the size of France or Texas. He was also implicitly acknowledging the weakness of the UN-African Union peacekeeping mission, UNAMID.

Meanwhile, in the south of Sudan, the non-Arab people of Blue Nile and South Kordofan states have been sealed off, bombed and starved since 2011. The same Sudanese armed forces now represented on the Transitional Military Council worked with the ousted president, Omar Bashir, to ethnically cleanse the area of what Khartoum saw as unreliable citizens. A few months ago, when the human rights NGO Waging Peace (which I founded) interviewed refugees who fled to South Sudan to escape the Sudanese militia, they found no enthusiasm to return.

A report by the Sudan Consortium – a group of human rights organisations – records an increase in the numbers injured and killed by Sudanese armed forces this year. It states: “Civilians in the two areas [Blue Nile and South Kordofan] have not noticed any meaningful change following the toppling of Bashir and the struggle for power between the Transitional Military Council and the civilian opposition forces.”

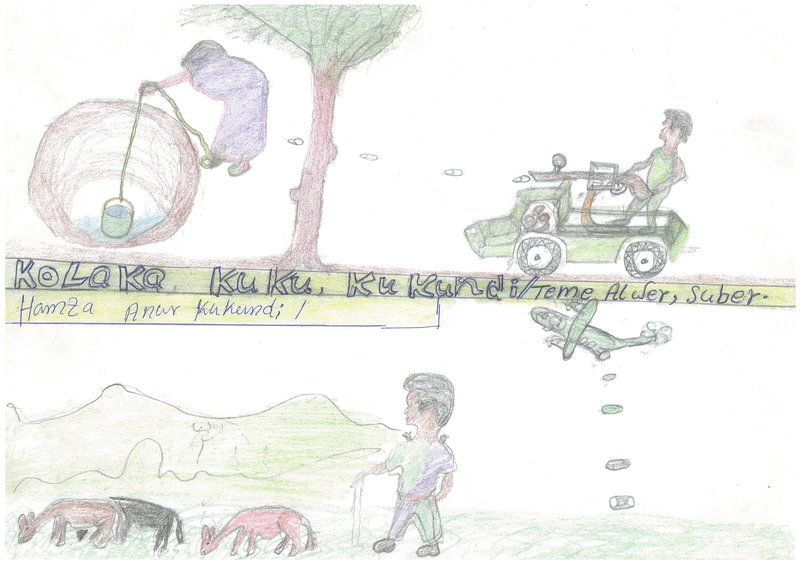

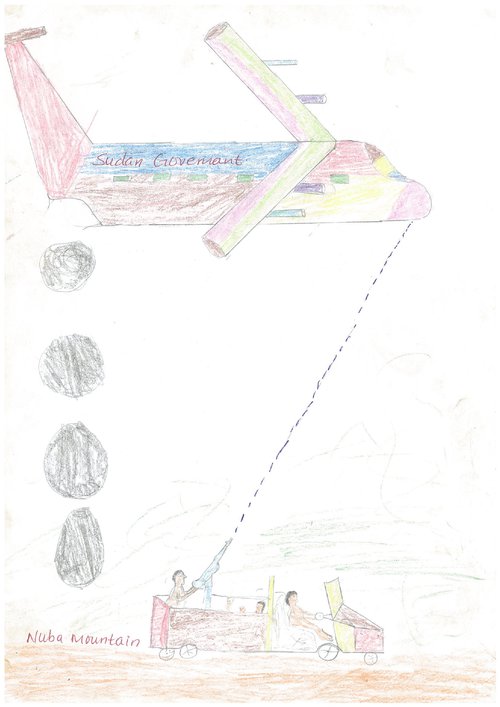

The children’s drawings accompanying this article illustrate the terror of daily life in the long-marginalised regions. They were collected by Waging Peace in a refugee camp on the South Sudan border last December.

One rule for Khartoum, another for provinces

Anger at the removal of subsidies prompted the massive anti-regime demonstrations which led to the fall of Bashir. Those protesters did not take to the streets in anger at the massacre of non-Arab citizens in Darfur, Blue Nile and South Kordofan over the years. More recently, while demonstrators in Khartoum protested about the RSF attack which killed five school children in El Obeid on 30 July, there had been little outrage when the RSF killed non-Arab Darfuri children in Kabra ten days earlier or attacked Darfur’s Jebel Marra region on 24 July.

According to Maddy Crowther from Waging Peace: "The violence recently seen in Khartoum's streets has long been meted out to those in Darfur, Blue Nile and South Kordofan, accompanied by a racist ideology that treats these individuals as second-class citizens. Although the agreement between the civilian and military delegations is welcome, there is a danger it just becomes power-sharing between Nile elites.”

The armed rebels from Sudan’s marginalised areas have pushed the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) – the civilian technocrats representing Khartoum’s protesters on the transitional authority – to prioritise the search for lasting peace in the country’s periphery. The rebels recently negotiated a separate deal with the FFC in Addis Ababa to this end. However, their deal was absent from the final FFC agreement with the Transitional Military Council. Whether this was by design or mistake, it bred suspicion that the provincials were being sidelined once more.

This may be symptomatic of the inexperience of the FFC, suggests Sudan expert Gill Lusk: “The FFC has not focused on the marginalised areas enough. This reflects their need for more political skills rather than their indifference, but therein lies the real problem: the lack of apparent strategy and politics. Added to which the FFC still has no formal and operational structure, eight months after the revolution.”

Containing Hemedti

While the opposition may struggle to maintain unity, their military colleagues on the transitional authority could also face divisions. Among the Sudanese regular army there is reportedly widespread distrust of Hemedti and his RSF militia. Hemedti controls much of Sudan’s lucrative gold trade, and his battalions of mercenaries earn him millions of dollars in Yemen (fighting on behalf of Saudi Arabia) and Libya (fighting for Khalifa Haftar).

Some Darfuris fear the regular army will keep him away from Khartoum by ‘rewarding’ him with Darfur, where the RSF will continue plundering natural resources, looting livestock and ethnically cleansing the non-Arab population. He is reported to have many local chiefs on his payroll there. In a worrying development, on 13 May, the Transitional Military Council decreed that all camps for internally displaced people in Darfur should be handed over to the RSF, an order resisted by the UN.

According to Maddy Crowther, “We would like to see a more fundamental discussion about what it means to be Sudanese, and a celebration, rather than whitewashing, of Sudan's diversity. The stakes could not be higher. We might otherwise be witness to 30 more years of bloodshed, bombings, rapes and targeted persecution. Sudan's people, all of them, deserve better."

The Forces of Freedom and Change face numerous hurdles: an economic crisis following decades of mismanagement and corruption under Bashir and an entrenched deep-state Islamist network in business, government bureaucracy, media and military. The civilians’ influence will also be tested because of their relative inexperience, compared with the seasoned politician-generals who have run Sudan for the benefit of the crony capitalist Nile elite since 1989.

Gill Lusk reflects the concerns of many Sudanese when she points out that Bashir’s former regime is lurking behind the TMC, especially in the all-important and powerful security structure. “The real test,” she says, “is whether optimism, courage and determination are enough to outwit and uproot them.”

*Rebecca Tinsley’s novel about Sudan, ‘When the Stars Fall to Earth’, is available on Amazon