|

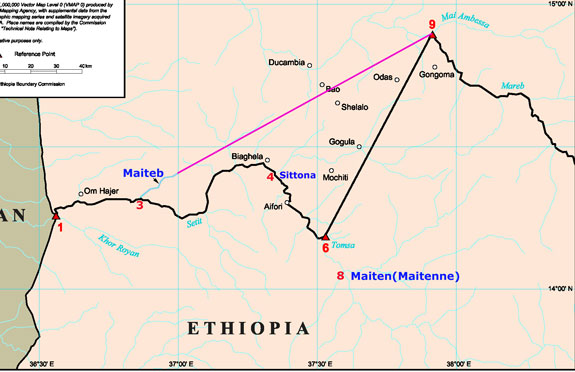

Dialogue-Skeptic by Conviction Tekie Fessehatzion The current cyber debate on dialogue with Ethiopia has taken a predictable turn: ear-piercing shrillness, embarrassing vulgarity and mindless name-calling, drowning the occasional nuggets of perceptive comments even from people generally not regarded political soul-mates. It’s a mystery why some among us are congenitally incapable of engaging in a civil discussion, without baring their fangs, or shaking their fists at those who don’t agree with them. Yet we must not allow the usual silliness of the intellectually frivolous of the “cut and paste” type who confuse glibness for profundity to deter us from talking to each other. Fortunately all is not lost. Among us there’s the more serious group or individuals, inclined to more sober refection, even when they are in disagreement. They deserve our respect and attention. We should listen to them with an open mind knowing full well that no one has a monopoly on wisdom of what’s good for Eritrea. There’s nothing inherently wrong with dialogue with Ethiopia, with opening communication to resolve mutual problems, to push a mutually beneficial agenda, to move towards normalization. If you don’t talk to your adversary, whom do you talk to? Talking about dialogue seems so easy, so straightforward. But dialogue can’t happen in the abstract. It must have a context. It must have an agenda, a road map. It demands a common frame of reference. If we have to talk, do we know what we would be talking about? Even if we think we know, does the other side have the same understanding of the definition of terms, scope, and parameters of what’s to be discussed? For dialogue to be successful one has to trust that the other party is engaged in the process in good faith There has to be a meeting of minds on the frame of reference, on the agenda; and once an agreement has been reached, there’s the utmost assurance it would be accepted and implemented. Those who are pushing for dialogue have to deliver on these very important points. Those of us who have made it our business to follow the tortuous peace process the past five years are dubious that the other side would come to the dialogue in good faith. Never mind that some of us never believed that the principal source of the conflict was Badme. But if our compatriots convince us that in the interest of real peace we should give up the EEBC’s delimitation instrument in lieu of a newly negotiated border, we would listen. It would be prudent to ask what the other party has in mind. When the government of Prime Minister Meles calls for a dialogue is it interested in finding a mutually beneficial solution, or is it trying to impose its version through dilatory tactics? If we agree to the proposal, what evidence is available that the Ethiopians would approach future negotiations in good faith? These are some of the questions that proponents of dialogue must not, should not, evade. We need answers to these questions because what’s at stake is nothing short of Eritrea’s territorial integrity, and with it, the quality of its sovereignty. Take, for example, what some of the proponents of dialogue seem to have in mind—trading Badme for peace. There’s nothing inherently wrong with trading a small patch of scrubland for real peace, or for another land of comparable area and value if that is all there is to the deal. Commonsense and past experience suggest that one has to be careful to make sure that the two parties are talking about the same territory with the same geographic dimensions. Is the “small patch of scrubland” the proponents of dialogue have in mind really what the TPLF government also has in mind? Indeed what may be Badme town to one side may be Badme town and plus to the other. Here it helps to review the record of statements of Ethiopian officials on the matter. Right from the start Prime Minister Meles has been talking about not just Badme town, rather Badme and its “environs.” Not only that, he’s adding sections of the Central Zone to the mix. Leaving aside the Central Zone for the moment, we have to ask: What is the geographic reach of Badme’s “environs?” We have two clues. One is in the Ethiopian submission of claims to the EEBC in 2002 for a line that stretches from a few kilometers from Um Hager straight to the junction of Mareb and Mai Ambessa. Ethiopia’s claim was to move the boundary at least 120km to the west. You are talking about half of Gash-Barka, Eritrea’s principal bread basket, the gold deposits at Agaro and the marble quarry nearby, and all valuable economic assets. The other clue is what Prime Minister Meles said in a recent interview about Badme being 40 to 60km inside Ethiopia. To confuse matters further, Meles said Badme is 800 meters from the delimited border. Are we really talking about 800 meters difference? Not really. In their report of July 8, 2002 EEBC’s investigators said that measured from the center of the town Badme is 1.8 km inside the Eritrean side of the delimited border. The question is: Where did the 800 meters come from when the EEBC said it was slightly less than 2km? If we go to a dialogue on this, whose figures do we accept? The difference between 1.8km and 800meters may not be much, but it does show the difficulty of getting an agreement with the Ethiopians on what EEBC actually said even when it’s written in black and white. Obviously the bait and switch tactic that has been so prevalent in most of the previous discussions, strikes again. You entice people to a dialogue on how best to deal with a measly 800 meters of land, then you say, “By the way the difference is actually greater than 800 meters, say, 60 km.” You scratch your head and you ask yourself, “How did an initial 800meters’ difference grow 75 times to 60km?” Then you wonder whether this is an honest mix-up of numbers, a misreading of what the Commission said, or a deliberate distortion to lasso Badme to the Ethiopian side of the delimited border. This is a point dialogue advocates have to ponder. Without an agreed upon frame of reference the futility of dialogue becomes crystal clear. Another example that makes good faith negotiations problematic is the Ethiopian leadership’s penchant for making official statements that are plainly untrue, or distortions of publicly known facts. I will give you two cases. June 5, 1998 was a turning point to the conflict. At 2:00 p.m. Asmara time Ethiopian Air Force jets bombed Asmara. Exactly at 2:50 p.m., the same day, in retaliation Eritrean Air Force jets bombed Mekele. The next day the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ethiopia issued a press release saying Eritrea initiated the bombing, and Ethiopia simply retaliated. The sequence of the bombings, and fighter planes taking off about half an hour or so later, was observed by neutral foreigners in Asmara. Yet official Ethiopia stuck to the story that Eritrea hit first, in effect arguing that what Ethiopia did at 2:00 p.m. was in retaliation to the 2:50 p.m. bombing of Mekele, a nonsensical sequence of events, no one could believe, but official Ethiopia put out in press releases. It’s difficult to discuss in good faith with people who make their own sequence of events totally the opposite of what actually transpired. The second case is more recent but making the same point. Take the recent back and forth exchanges between Ethiopia’s top two leaders and Sir Elihu Lauterpacht, President of the EEBC, on what the Commission said or didn’t say. It’s one thing to challenge the Commission because one wants to argue that the basis for its Decision was erroneous, but to tell the Commission how to read and interpret its own Decision after editing crucial information, defies logic. In his September 19 letter to the Security Council, Meles Zenawi wrote:

Sir Lauterpacht politely but firmly reminded the Security Council that Prime Minister Meles’ textual reading let alone interpretation of the Commission’s April 13 Decision was incorrect

Foreign Minister Seyoum went a step further. He told the Security Council that the President of the Border Commission’s textual or interpretive reading of the April 13 Decision was incorrect in effect editing the Commission’s words:

The President of the EEBC talked about Points 6 and 9 as the two reference points the Commission had in mind, but the Foreign Minister insisted that the EEBC meant to say Points 4 and 9 and not 6 and 9. One assumes that if the EEBC meant to say Points 4 and 9 wouldn’t it just say 4 and 9? When it said 6 and 9, it meant just that: 6 and 9. Why did Ethiopia’s Foreign Minister insist the Commission said Point 4, when the Commission reference point was Point 6? The answer is not hard to guess. By moving Point 6 to Point 4, Ethiopia’s claim moves 60 km deep into Eritrea. If Ethiopia were to prevail in moving to Point 4, when the text actually said Point 6, it would be entitled to about a quarter of Gash-Barka. Remember in its initial claim before the EEBC, Ethiopia asked for half of Gash-Barka, (starting from Point 3 going to Point 9) and when that was denied, Ethiopia comes back and in effect says, at least give us half of what we claimed. When the Commission denied Ethiopia’s claim the second time, Ethiopia said it had lost all confidence in the Commission’s impartiality. It behooves dialogue advocates to remember the EEBC’s experience in its dealing with Ethiopia’s leaders. The point is that proponents of dialogue have to tell us in advance how much land is in “play” as a trade-off for real peace. There must be full disclosure, absolute transparency on the “terms of trade” so that people can have some idea what’s being exchanged. Our skepticism about the seriousness of the Ethiopian leadership in finding a peaceful way out of the problem has been forged in the crucible of our disappointments the past five years. In the current situation the context is the wretched war, and the peace process that’s about to be unglued because one side reneged on terms of the initial agreement. The track record is there. We can’t wish it away because the other side is dangling the possibility of a short-term peace without telling us what the price would be. Our skepticism is solidly grounded on experience. Once upon a time we thought the parties had agreed to a process that required both to accept the Decision of a neutral boundary commission as final and binding. This was the frame of reference. If they reneged on a signed deal, what makes one think they won’t renege the second time? If they practiced bait and switch too many times in the past, what guarantee do we have they won’t employ it one more time? Don’t get me wrong. We are aching for peace. Any one can be for dialogue just as anyone can be in favor of peace. The point is advocates of dialogue need to divulge what’s in the auction block. It’s a matter of prudence to ask in advance what the price of the purported peace would be, assuming we will be getting real peace. To ask in advance the parameters of the dialogue before one makes a decision to participate or not, should not be considered high treason or misdemeanor. Even if there’s an agreement on the parameters, and a decision has been reached, how can we be sure the other side would implement what has been agreed to? This is not an idle question. We have been disappointed before. The Algiers Agreement said the Commission’s Decision would be final and binding. In fact when the Decision was read on April 13, 2002, this is what Foreign Minister Seyoum said the same day, “the ruling of the border commission is fair and appropriate. Ethiopia is fully satisfied with the decision of the boundary commission…” Two days later, Prime Minister Meles added his voice of approval, “The ruling vindicates Ethiopia’s land claims…..The decision of the boundary commission has awarded Ethiopia all the contested areas it had claimed.” And one of the principal lawyers who argued Ethiopia’s claims before the EEBC, Seyfe Selassie Lemma Kidane said, “Ethiopia came out victorious because the commissioners made the right decision based on the law and their own principle.” Yet one year later, the Ethiopian leadership changed its mind. Seyoum called the ruling “unjust.” Meles found the Commission’s Decision he once hailed a year ago “unjust miscarriage of justice.” Indeed the Ethiopian leadership may have its own reason why it condemned what it praised only a year ago. The relevant point for us is that one has no assurance that what is accepted to-day will remain accepted a year from now, a point advocates of dialogue need to think about. To agree to the nature of dialogue Ethiopia is requesting is to give up the certainty of a delimited border, to give up a legally recognized border for one that may or may not be decided for a long time. Reopening delimitation, because that’s what bilateral discussion on the border would eventually mean, is a monumental risk, without assurance of success. We hope that Ethiopia’s leaders come to their senses and get on with demarcation on the basis of the April 13 Decision and the Algiers Peace Agreement. It’s to every one’s advantage. If they don’t, then surely the guarantors of the Algiers Agreement have to step in and discharge their responsibility to the people of Ethiopia and Eritrea: enforce compliance. Essentially the dispute now is between the guarantors and Ethiopia. The Security Council has a choice: either force compliance with the Commission’s Decision or leave UNMEE where it is at a cost of at least $200 million a year indefinitely. It’s unlikely that Meles will proceed with demarcation, on his own free will, and without pressure from the Security Council, unless he believes that it is obscenely advantageous to Tigray at Eritrea’s expense. Make no mistake; the conflict was never about Badme. It was about something much more. It was about truncating Eritrea beyond recognition, and ultimately diluting its sovereignty. Unless someone comes forward with better insight or logic about the efficacy of dialogue on demarcation let alone delimitation, some of us will remain dialogue skeptic not only for now, but also tomorrow, and the days after. No apologies. Absolutely none. |