SCOTT DUDELSON / GETTY / PAUL SPELLA / THE ATLANTIC

SCOTT DUDELSON / GETTY / PAUL SPELLA / THE ATLANTICBut now, less than a year later, Hussle’s connection to his fans, Eritrean and American alike, has taken on a far more tragic valence. On Sunday afternoon, Hussle was fatally shot outside the store he co-owned in South L.A., the neighborhood Hussle celebrated in his music, advocacy, and philanthropic ventures. The Los Angeles Police Department has since apprehended a suspect in the case, but the rapper and activist’s killing remains a devastating blow to his family and to fans around the world, many of whom have likened him to the late Tupac Shakur.

The news of Hussle’s death spread quickly, especially among the rapper’s supporters—that day, an impromptu vigil was held outside the Asghedom brothers’ store, The Marathon Clothing. Local fans and friends lined the corner of Victoria Avenue and Crenshaw Boulevard, playing Hussle’s music and reflecting on a man who “poured positivity into the streets,” as one attendee told the Los Angeles Times. Within 24 hours, Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook users had begun sharing flyers for candlelight vigils organized in cities around the country, including Atlanta, Chicago, New York, and Dallas.

Many of the memorials were organized specifically by Eritrean diasporic communities, their ad hoc appearances a direct reflection of the rapper’s importance to those who share his heritage. Among the first gatherings announced after the rally in Los Angeles was a vigil to be held Thursday in Washington, D.C., which boasts one of the largest East African populations in the United States.

The past year has seen the countries thaw their diplomatic tensions, and many Ethiopians and Eritreans refer to a sense of shared identity with the politically complicated umbrella term habesha. Indeed, the two nations share many cultural hallmarks—among them, food and some languages, including naming conventions. Ermias Asghedom, for example, is the kind of name that immediately evokes the Horn of Africa. Even so, many young Eritrean Americans, including Hussle and the actor Tiffany Haddish, grew up bristling at how often they were mistaken for their Ethiopian counterparts in the West—and feeling a deep sense of pride in their nation’s struggle for independence.

The Asghedom brothers, who were raised in their American mother’s Los Angeles home for many of their formative years, first traveled to Eritrea in 2004, when Hussle was 18. “As I got older, my pops tried to keep me involved with the culture by telling me the stories of the conflict between Ethiopia and Eritrea, how he came to America, and about our family back home, because all that side of my family, my aunties, grandparents, is in Africa,” he told Complexin 2010. That first visit “put me in touch with my roots. If you don’t know your full-throttle history, the whole story of how you came to where you are, it’s kind of hard to put things together,” Hussle said. “That filled in a blank spot for me, as far as understanding myself.”

If Hussle’s trips to Eritrea helped the musician connect his American upbringing to his African roots, then his music—and the simple fact of his prominence—did the same for younger habeshas. The 24-year-old Ethiopian and Eritrean American rapper Aminé recalls discovering Hussle in his childhood—and finding inspiration to pursue music despite the admonitions he’d heard about choosing a stable career. “The first ever habesha person I ever saw do anything, like, dope that wasn’t a doctor or lawyer was Nipsey,” the Portland-bred musician said when we spoke over the phone recently. “I seen him and I was like, ‘Wow this is crazy!’ And I showed it to my mom when I was in high school and she was like, ‘Oh he’s Eritrean?!’ She was super shocked that someone was successful in something that wasn’t what the norm was.”

Belayneh, whose work in the D.C. area falls largely within entertainment and event planning, also looked to Hussle as a possibility model for creative pursuits. “It’s that extra step of connection. Not only was he the template of success for so many people, but for us, specifically, there’s that deeper root, like I know exactly what he could be going through in his upbringing, his household, the values that people have instilled in him family-wise,” Belayneh said of the late rapper’s significance to habesha youth. “So for us, it’s like the American dream is that much more attainable.”

Part of Hussle’s influence stemmed from his straightforward detailing of the violence and inequality he regularly faced in South Central, and in America writ large. In his music and in interviews, he didn’t shy away from discussing his gang affiliation—or from critiquing the systems of discrimination that foster violence within his neighborhood and others like it. Through the fact of his life, he also validated the experiences of young habeshas around the country whose trajectories didn’t bear the hallmarks of neat success stories. Hussle’s public persona wasn’t one concerned with adhering to restrictive notions of respectability.

Hussle wasn’t perfect, but he was certainly real. For many who belong to an immigrant group that grapples with both intra-community pressure and external hostility from broader American society, his openness about hardship was refreshing. Another New York City vigil coordinator, Abraham Paulos, spoke of Hussle’s transparency about his street life. “It’s a very, very complicated kind of existence,” the Eritrean American organizer said. “And some of [the youth] do have to find safety in the streets and in gang life. So [it’s important] to say, ‘We’re not gonna shun you; you’re not a disgrace to our community.’”

In the days following Hussle’s death, many of the expressions of grief from fans have included a poignant hashtag: #TheMarathonContinues. The virtual rallying cry takes its name from one of Hussle’s mixtapes, and it’s also a nod to the rapper’s store, as well as to the metaphor he often used to describe his life and career. (Marathons are also, it’s worth noting, the athletic event in which East Africans are most likely to claim gold.)

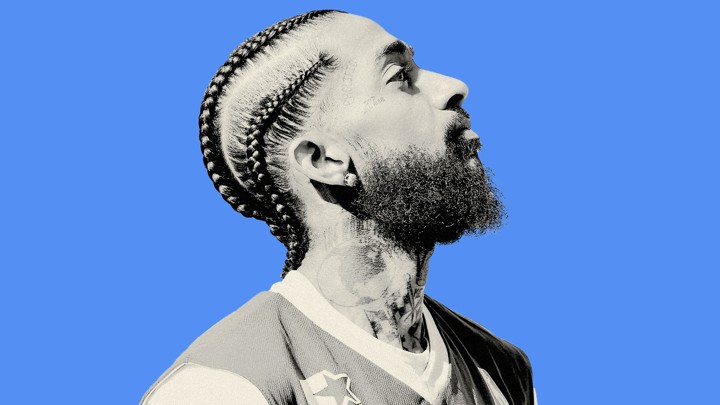

Many online dedications and fan-art renderings of Hussle have included a specific set of photos, in which he posed against a stark, royal-blue background. The Seattle-bred Eritrean American photographer Meron Menghistab, who shot the iconic photos for a March 2018 feature on BET, was on a flight when Hussle’s killing was first reported. “It was overwhelming,” he said of the news and attendant virality when we spoke via WhatsApp. “[My] first reaction [was], What does this mean for people who are still living that life? I think for me, that was the hardest part.”

In D.C., the rapper’s music has played at various Ethiopian- and Eritrean-owned establishments in the days following his death. “Hussle & Motivate” soundtracked a hookah lounge on U Street Monday evening; it played again at a different venue the following night, preceded immediately by Aminé’s “Caroline.” A day later, “Hussle & Motivate” pumped through speakers again, this time followed by the mournful Victory Lap track “Double Up.” Though Hussle has hovered over the nightlife and habesha corners of the city, the District’s formal honoring of him will happen Thursday at Malcolm X Park.

The New York City vigil, for its part, will be held at the General Grant National Memorial uptown, where local Eritreans and Eritrean Americans gather each year to celebrate Eritrean Martyrs Day. The holiday, which is also celebrated in Eritrea, pays tribute to the people who lost their life in the country’s long fight for independence. The event flyer, which features a photo of Hussle’s father, refers to Hussle as a martyr, as well. (In one exchange on the city’s habeshaemail listserv, to which I belong, a reply mentioning that Thursday evening might bring rain was met with a swift admonition: “It’s a marathon! Dedication and commitment!”)

The several dozen vigils, which began early this week and will extend through next week, will now take place in international cities, as well—among them, Vancouver, Perth, and Oslo. Hussle, or “Nebsi,” as many habeshas call him, will also have home-going services in both Asmara, the capital of Eritrea, and Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. (Of the nickname, which is akin to being called “homie,” Hussle told Temesghen, the Eritrean journalist, “I was educated about the Tigrigna link to my name recently, and I am just so glad it makes sense in Tigrigna and there is no need at all to correct it. Let it be the way it is. That is how I want to keep it with my Eritrean friends and fans.”)

Those concerned with honoring his legacy have expressed, above all, a desire to remember Hussle’s commitment to preserving the communities he cared most about. The rapper’s father, Dawit Asghedom, worked at the Marathon Clothing store alongside his sons, but he was also invested in fighting for and with black people beyond Los Angeles and Eritrea. For volunteers such as Paulos, recognizing Hussle’s ties to L.A., and to black American history, is as key as remembering his Eritrean heritage: “Him being a part of … the habeshacommunity and the black community in the U.S., and to be able to bring it all together and find a place of love for each other as black people, is a really important thing,” Paulos said. (The rapper’s relationship with the African American actor Lauren London has been gutting to think about in the past several days.)

For Aminé, himself an artist, paying Hussle’s gifts forward is a particularly urgent task. “Seeing someone like him do what he did for his community always made me feel like I wasn’t doing enough, and it inspired me to just wanna do more,” the rapper said. “Even with his death, it hurts and there’s no words to explain it … I wanna mourn, but I’m also inspired by it as well.”

“It … makes me feel like I have to put all hands on deck and just talk to my parents and talk to anyone I possibly can to figure out how I can help my community,” Aminé added. “Because you kinda feel ashamed of yourself that Nipsey died—he was doing so good and now we kinda have to pick up the pieces and continue that marathon that he was talking about.”

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.